-

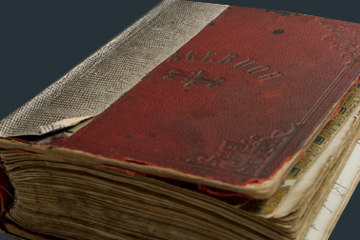

Conductress in a Vienna tram, photo from Das interessante Blatt of 8 July 1915

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall -

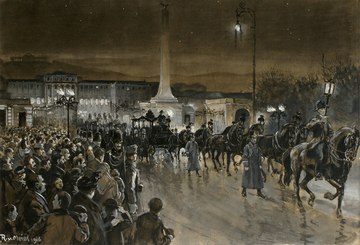

“Traffic at the Vienna Opera House crossroads”, caricature from Der Morgen (issue of 19 August 1918)

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall -

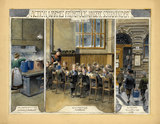

Moritz Ledeli: “Hot breakfast for our schoolchildren” campaign, watercolour, 1916/17

Copyright: Wien Museum

Partner: Wien Museum

As the war progressed, the indications that a decisive change was taking place became increasingly obvious. The initial euphoric patriotism and enthusiasm gave way to disillusionment and often bitterness. The year 1916 was the decisive turning point in the perception of the war due to the increasing shortages and the unpromising news from the front. Emperor Franz Joseph I, the most important representative of the ‘world of yesterday’, also died that year.

The death of Emperor Franz Joseph and the imperial funeral on 30 November 1916 may be seen as a symbolic swansong. The unhappy course of the war, the dissatisfaction with the Habsburg absolutism and the shortages meant that the prevailing mood of the people of Vienna, rather than sadness at the passing of their emperor, was a vague indifference. Many appeared already to realize that they were saying goodbye to the ‘world of yesterday’. There were plenty of signs: the hunger was taking on dramatic proportions, (hunger) demonstrations were on the increase, and petty acts of violence became more frequent. The channelling of the mood was shown not least by the assassination of Minister President Stürgkh in October 1916 by Victor Adler’s son Fritz. The population saw itself increasingly as victims of the war and, in view of the inadequate logistics and the inability to fight inflation and deal with profiteers, of the Habsburg regime, the state and the community.

Goodbye to the ‘world of yesterday’ also meant goodbye to earlier customs and practices. The shortages, for example, had a positive by-product of sorts, bringing about a change in social and welfare policies, although classic emergency welfare measures like soup kitchens and the evacuation of children still predominated. A central welfare office for soldiers and their dependents was set up immediately after the start of the war. The new attitude was seen most clearly in child and juvenile welfare, culminating in 1916 in the establishment of a Municipal Juvenile Office. In May 1917 the Arbeitsfürsorgeamt (Labour Welfare Office) replaced the municipal labour and services exchange, and in July 1917 the Municipal Welfare Office was established. The introduction and extension of rent control was a particularly enduring measure.

Improvements also came in the position of workers in companies. Because of the supply shortages and unrest, the authorities sought cooperation, especially as the trade unions had called a truce for the duration of the war. The workers ended the First World War in a stronger position, as seen in the many business and economic bodies such as the parity and complaints commissions. Even before the republic was proclaimed, unemployment benefits were introduced for all industrial and salaried workers. The workers’ demands for an end to the war or the lifting of military law and the cautious approach by the authorities were influenced amongst other things by the Russian Revolution. Many soldiers returning from Russian imprisonment reported on the success of the revolution.

The appearance of Vienna had also changed. It had turned into a garrison and hospital city, and even the public buildings on the Ringstrasse such as the university or parliament had been converted into hospitals. Long lines of people were to be seen forming wherever there was something on offer. Conductresses punched tickets on the trams as women infiltrated some male domains, not without resistance and general scepticism and irritation.

In 1917 and 1918 the omnipresent shortages, hunger and hardship became even worse. They gave rise to strikes in those years, mostly caused by food shortages. The social tensions culminated in October and November 1918 when the imperial army was disbanded, the war industry broke down and the centuries-old state order finally collapsed. The year 1918 marked a schism at the political, social and economic levels. That year Victor Adler, Gustav Klimt, Otto Wagner, Kolo Moser and Egon Schiele, all major representatives of the artistic avant-garde in Vienna 1900, also died, once again marking the end of a glorious era.

Translation: Nick Somers

Berger, Peter: Die Stadt und der Krieg. Wiens Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft 1914-1918, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 210-219

Grandner, Margarete: Kooperative Gewerkschaftspolitik in der Kriegswirtschaft, Wien/Köln/Weimar 1992

Healy, Maureen: Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. Total War and Everyday Life in World War I, Cambridge 2006

Maderthaner, Wolfgang: Krieg und Frieden, in: Csendes, Peter/Opll, Ferdinand (Hrsg.): Wien. Geschichte einer Stadt, Band 3: Von 1790 bis zur Gegenwart, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2006, 317-360

-

Chapters

- The growing city: Vienna on the eve of the First World Wa

- The war takes over the city

- Rebuilding for war: barracks and hospitals in Vienna

- Vienna as a refugee camp

- Vienna as a centre of the war economy

- Goodbye to the world of yesterday

- Self-help: unofficial allotments and deforesting the Vienna Woods

- Overthrow of the old values: post-war Vienna