Vienna was not a theatre of war, nor did it suffer destruction as a result of the fighting. Externally it changed very little, but the war quite clearly left its mark. War propaganda and patriotic enthusiasm dominated daily life in the city. The euphoria waned markedly as the war progressed and the supply situation became increasingly critical.

The First World War confronted the population of Vienna with a completely new situation at a number of levels. Daily life became an increasing trial, as every aspect and activity had to be planned to the last detail: how and where to get food, what it was possible to eat, how to survive with limited resources. There was a shortage of practically everything, and by the time the war ended the majority of the population was physically and mentally exhausted.

The war also changed everyday political life. The Vienna city council met at the end of September 1914 to retroactively approve a wealth of temporary orders (use of schools as hospitals, emergency plans for trams, etc.). The council was not to meet again until February 1916, and all matters of importance for the war became the responsibility of the newly created ‘Obmännerkonferenz’ (chairmen’s committee). There was thus little system to local politics during the war, although the city retained its housing, juvenile welfare and health departments. The parties agreed to put aside their fundamental differences of opinion until early 1918.

As the war progressed, the mayor and city council became more and more dependent on the military administration, but their responsibilities increased markedly at the same time: recruitment, the welfare of refugees, invalids and surviving dependents, and food supply had also to be financed for the most part by the communities, which placed an extremely heavy financial burden on the city.

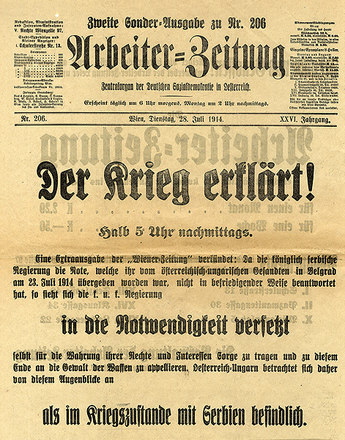

The war had both a direct and an indirect impact on the city. The declaration of war on 28 July 1914 was greeted for the most part with euphoric enthusiasm, patriotic parades and demonstrations, accompanied by loud cheering of the emperor, fatherland and army. The press, led by the pro-government Neue Freie Presse, stirred up enthusiasm for the war. Many weekly illustrated magazines devoted themselves to reporting on the war and showing pictures of it. Even at the start of the war, charitable gifts (socks, balaclavas and also food) were organized for the troops as an instrument of propaganda. Patriotic banners proliferated on empty spaces or trees in the city, and on carriages and trains leaving Vienna.

A postcard from 1914 shows Mariahilferstrasse decked out for victory. The departure of the first volunteers was dramatized as a patriotic event. The public space was nationalized and placed at the service of the war, or more precisely propaganda for it. The ‘Iron Soldier’ was erected on Schwarzenbergplatz as an incitement to the Viennese to support soldiers, widows and orphans. After making a donation, inhabitants could hammer a nail into it. In autumn 1915 other wooden soldiers were erected. War propaganda came in various forms as people wore sewn-on badges, pins and cockades. In the ‘gold for iron’ campaign, wedding rings were exchanged for iron rings and gold objects for metal. Collections were organized for practically everything: shoes, clothes, metal, bottles, newspapers, and most of all money.

The war also had a diverse influence on entertainment in Vienna. All balls for the 1914/15 season were cancelled, and New Year’s Eve was a quiet affair. The entertainment industry nevertheless soon had an important diversionary function. The Burgtheater was initially closed but then reopened to show propaganda plays, and politics even found its way into operetta. The most popular film was Wien im Krieg.

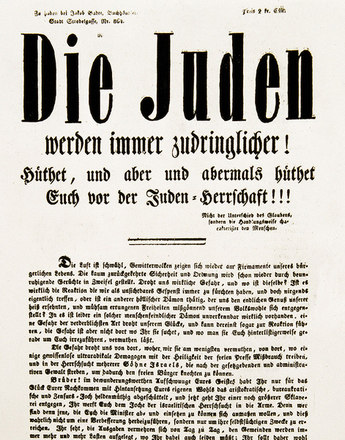

Xenophobia of the basest sort was widespread and visible, initially aimed at the enemy but then more and more at the Jewish refugees streaming into the city from the war zones. Slogans such as ‘Serbien muss sterbien’ (Serbia must die), ‘Jeder Schuß – ein Ruß’ (a Russki with every bullet), ‘Jeder Brit – ein Tritt’ (a Brit with every hit) were taken up with enthusiasm. An important aspect of the propaganda was the indoctrination of schoolchildren, and the ‘school front’ became a significant part of the ‘home front’. This reached down to toys, and war games were widely distributed.

Information and propaganda became intermingled. While a group of industrialists led by Julius Meinl launched a peace initiative in late 1915 to end the war, the Viennese film producer Count Alexander (Sascha) Josef von Kolowrat-Krakowsky started his weekly newsreel, Sascha-Kriegswoche. At the same time, exhibitions began to provide information on the military and economic situation, for example in the Trenches and Navy Show and in the war exhibition at the Prater in 1916.

Translation: Nick Somers

Holzer, Anton: Die andere Front. Fotografie und Propaganda im Ersten Weltkrieg, Darmstadt 2012

Mertens, Christian: Richard Weiskirchner (1861-1926). Der unbekannte Wiener Bürgermeister, Wien/München 2006

Patzer, Franz (Hrsg.): Das Schwarz-Gelbe Kreuz. Wiener Alltagsleben im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 1988

Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas: Die Pflicht zu sterben und das Recht zu leben. Der Erste Weltkrieg als bleibendes Trauma in der Geschichte Wiens, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 14-31

Seliger, Maren/Ucakar, Paul: Wien. Politische Geschichte 1740-1934. Entwicklung und Bestimmungskräfte großstädtischer Politik, Teil 2: 1896-1934, Wien 1985

-

Chapters

- The growing city: Vienna on the eve of the First World Wa

- The war takes over the city

- Rebuilding for war: barracks and hospitals in Vienna

- Vienna as a refugee camp

- Vienna as a centre of the war economy

- Goodbye to the world of yesterday

- Self-help: unofficial allotments and deforesting the Vienna Woods

- Overthrow of the old values: post-war Vienna