-

Assembly of aircraft components in the carriageworks factory in Favoriten, Vienna, photo from Österreichs Illustrierte Zeitung, 13 August 1916

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall -

Theo Zasche: “Cis and Trans”, Caricature from Österreichische Volkszeitung of 21 October 1917

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall -

“Rural ballade” – assaults on women hoarders, caricature from Die Muskete of 5 September 1918

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall

With the outbreak of the war, the economy had to be adapted to the new situation, and it contained several planned economy elements and dictatorial characteristics. This process was combined with the militarization of businesses and working conditions. A shortage of labour soon became apparent, compensated increasingly through the use of women. The lack of preparation for a war of this length and intensity can be seen as well in the dire supply situation to the population of Vienna, with shortages practically across the board.

The first signs of an economic crisis were already being felt before the war, and it intensified with the outbreak of war and the need to switch from peacetime to wartime production. Many businesses and companies had to close, resulting initially in higher unemployment. Soon after the start of the war, businesses necessary for the war effort, above all arms and ammunition factories, were put under military law and adapted for wartime requirements. Worker safety regulations were suspended and everyday work militarized. Income and working conditions were catastrophic. Businesses reacted initially to unrest, mostly as a result of hunger and food shortages, by extending and tightening military service law. Improvements in the workers’ situation, for example through the establishment of joint complaints committees, were to be seen from 1917 onwards.

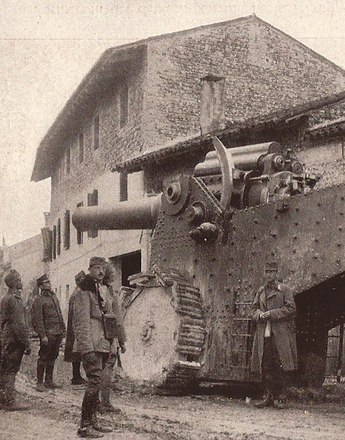

Vienna was the centre of the war economy. In November 1916 there were 1,587 registered companies in Vienna working for the Austro-Hungarian army administration and employing around 700,000 people. The Arsenal alone expanded into a huge arms production facility with as many as 20,000 employees. Whereas sectors important to the war effort such as the metal, mechanical and automotive engineering, aviation and electrical engineering industries soon expanded, some sectors of the consumer goods industry, such as the textile and clothing industry, luxury and export goods and the building industry practically collapsed. Because of the war economy, there was a shortage of labour in some sectors, and the recruitment of skilled workers soon became a serious problem. As a replacement for conscripted workers, younger and older workers, prisoners of war and above all women were called upon to work in the armaments industry and other industrial sectors, and in civilian and military services, particularly, for example, the municipal transport system.

The government issued war bonds to finance the war with much propaganda and the promise of high yields. At the end of the war these pieces of paper were to prove worthless.

The Austro-Hungarian economy was not prepared for the length and extent of this war, as can be seen most clearly from the supply of food and heating material. Agriculture was hardly mechanized, and the exclusion of the Central Powers from the world market as a result of a blockade by the Entente, the absence of the agrarian Galicia and continuous friction with Hungary meant that alternatives had to be sought. The imperial decree of October 1914 and the War Economy Empowerment Law of July 1917 served as the basis for the establishment of a planned dictatorial economy characterized by rationing, coupon-based supply systems, price ceilings, etc. The central war offices played an important role in the war economy. The first such office was the Kriegs-Getreideverkehrsanstalt (War Grain Trade Institute) set up in 1915. A total of ninety-one offices of this type were established, including twenty connected with food, such as the Stelle für städtische Lebensmittelversorgung (Municipal Food Supply Office), created in December 1916. The private economy gave rise to considerable criticism, however, and there were many cases of mismanagement and personal enrichment.

By 1915 shortages of many staple foods were occurring, and the police reported long queues for certain products. Bread and flour coupons were introduced in April 1915 as the first incisive rationing measures, followed in March/April 1916 by coupons for sugar, coffee, milk, and fat/butter. Potatoes and jam were rationed from 1917 and meat very late on in September 1918. In spite of the fixing of price ceilings, speculation and hoarding drove prices upwards, with 150 per cent inflation in 1915 and 200 per cent in 1916. The district courts were full of cases of profiteering. People felt betrayed by the food offices and also by small businesses. The names of convicted profiteers were announced in ‘pillory lists’ or posted in public. Commodities were in increasingly short supply from 1916 onwards.

Those with an allotment could improve their personal situation by planting vegetables or breeding animals, particularly rabbits. Necessity is the mother of invention, and the food shortages led to the use of various ersatz materials, extreme thrift and creativity. Waste was very important in this regard – fruit kernels for the production of oil, for example. Propaganda was employed to explain the food shortages and rationing. Cookery courses and war cookbooks showed how ersatz meals could be made with the simplest means, and new cooking utensils like the economical ‘cooking box’ were also presented. ‘The term “ersatz” became … a symbol for the disastrous food situation in the First World War.’ Ersatz meat, ersatz sausage – there was practically nothing that could not be replaced. The city council also attempted to counter the food shortage by setting up soup kitchens. In 1916 some 54,000 people were fed in this way, and by the end of the war their number had risen to 134,000 people per day.

There were also shortages of raw materials like nonferrous metals. There was no petroleum, candles or coal, wood and feed. The shortage of cotton paralyzed the textile industry. A further Achilles heel in the Austrian economy was the transport system and the inadequate logistics governing it.

Pictures of people waiting hours in line, above all women, children and youths, became commonplace: queues in front of shops, market stands, queues for welfare payments, tram and entrance tickets and at soup kitchens were a normal and everyday fact of life. The potential for aggression also grew as a result. In spite of the presence of the police to calm the situation, petty criminality and violence increased as the war went on. Youths formed gangs, shops were attacked and plundered, food transports hijacked. Hunger simply put people on the warpath.

Translation: Nick Somers

Enderle-Burcel, Gertrude: Denn Herrschaft ist im Alltag primär: Verwaltung. Verwaltung im Ausnahmezustand – die Wiener Zentralbürokratie im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 274-283

Healy, Maureen: Eine Stadt, in der sich täglich Hunderttausende anstellen, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 151-157

Healy, Maureen: Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. Total War and Everyday Life in World War I, Cambridge 2006

Maderthaner, Wolfgang: Krieg und Frieden, in: Csendes, Peter/Opll, Ferdinand (Hrsg.): Wien. Geschichte einer Stadt, Band 3: Von 1790 bis zur Gegenwart, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2006, 317-360

Wegs, Robert J.: Die österreichische Kriegswirtschaft 1914–1918, Wien 1979

Weigl, Andreas: Kriegsindustrie. Die Wiener Wirtschaft im Dienst der Kriegsökonomie, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 220-231

Quotes:

"The term "ersatz" became …": Brenner, Andrea: Das Maisgespenst im Stacheldraht. Improvisation und Ersatz in der Wiener Lebensmittelversorgung im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 141 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- The growing city: Vienna on the eve of the First World Wa

- The war takes over the city

- Rebuilding for war: barracks and hospitals in Vienna

- Vienna as a refugee camp

- Vienna as a centre of the war economy

- Goodbye to the world of yesterday

- Self-help: unofficial allotments and deforesting the Vienna Woods

- Overthrow of the old values: post-war Vienna