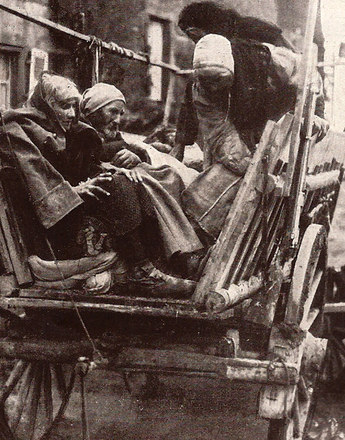

The war became increasingly present in Vienna. Shortly after it started, thousands of refugees, including many Jews, began to stream into the city. Neither the city council nor the government was adequately prepared for this situation. And within the population, envy, aggression and increased anti-Semitism soon became evident.

Thousands of refugees already started streaming into the city in the first winter of the war as they fled from the Russian offensive. The Zentralstelle der Fürsorge für Kriegsflüchtlinge aus Galizien und der Bukovina (Central Welfare Office for War Refugees from Galicia and Bukovina) was set up at Zirkusgasse 5 in the 2nd district in September 1914. After Italy entered the war in May 1915 it was renamed Zentralstelle der Fürsorge für Kriegsflüchtlinge (Central Welfare Office for War Refugees).

Most of the completely destitute refugees were provided free medical treatment and medicine, clothing, food and housing allowances and, if necessary, accommodation in an emergency shelter. The rapid establishment of a municipal refugee centre was due to the determination of mayor Weiskirchner, but at the same time he also attempted to get rid of these persons as soon as possible. In December 1914 the arrival of further refugees was prohibited, and housing and food became scarcer and scarcer.

The Arbeiter-Zeitung reported in September 1914 that 70,000 people from Galicia and Bukovina had fled to Vienna in that month alone, a fifth of them being Jews, and a month later there was talk of 125,000. A notification by the Ministry of the Interior spoke of 137,000 refugees in Vienna, including over 77,000 Jews. These figures referred only to registered and poor refugees, and the actual number might well have been higher. At its height, there were almost 200,000 refugees, of whom 150,000 were supported by the state. In May 1916 there were said to be 37,000 state-supported refugees in Vienna, including 20,000 Jews, and a further influx increased the number of destitute Jewish refugees by May 1917 to around 40,000. After 1915 the state support per person covered only a quarter of the living costs. The desire to return and the pressure to do so were both great, as can be seen from the dwindling number of refugees in Vienna. On 1 September 1918 there were 20,081 state-supported refugees, including over 17,000 Jews. Estimates, including persons with their own source of revenue or earnings, put the number of refugees remaining in Vienna at the end of 1918 at between 25,000 and 39,000.

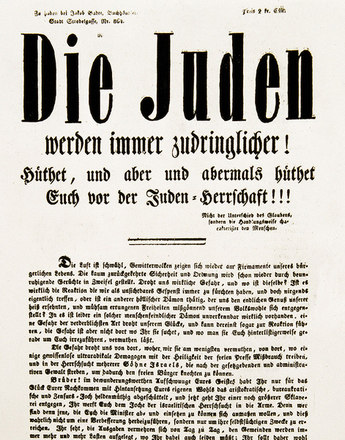

The Austrian ministries were unable to cope with the wave of refugees and the organization of transport, housing and food for tens of thousands of people. Some members of the population were initially helpful and supportive, but rejection and prejudice, reinforced by the critical situation in the city as a whole, soon predominated, particularly against Jewish refugees from the east. In autumn 1914 private refugee organizations were already complaining about the unsympathetic mood, particularly in Vienna, where refugees were seen as ‘shameless intruders’ of a ‘hostile disposition’.

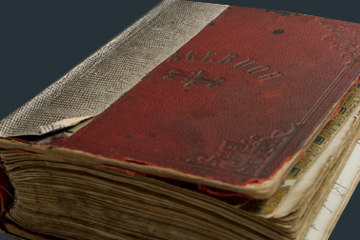

The Jewish refugees in particular – many of whom had hoped that they would be coming to an ‘earthly Jerusalem’ – were met with great resistance from the population and increasing anti-Semitism. This xenophobia intensified as the war progressed, the supply situation became more critical and the military debacle in the north-east of the Monarchy became evident. Refugees were used more and more frequently as scapegoats blamed for the outbreak of epidemics or the tense situation on the housing market. The accusation that they were taking advantage of the local inhabitants by pushing up prices was also part of the standard anti-Semitic rhetoric. This mood was intensified by the propaganda of the Christian Socialist party and German Nationalists. The ongoing records by the Central Office for War Refugees during the war shows how most of the war refugees were coping in reality, the poverty in which they lived, the dire housing situation, the hunger and disease.

Private charity organizations were basically responsible for looking after the refugees, but most specialized in just one nationality or a certain social class, e.g. the Vienna Aid Committee for Refugees from Galicia and Bukovina, which only dealt with better-off newcomers. The Central Welfare Office for War Refugees answerable to the Ministry of the Interior formed an exception, organizing the payment of refugee allowances, accommodation in and provision of homes for young girls, nurseries, children’s homes, the railway station service, clothing distribution and more. The total outlay for the Central Office in Vienna alone was 94.5 million crowns in 1918, and state expenditure as a whole was considerably more.

One problem faced by the refugees was the acquisition of a work permit. When the hostile attitude to refugees within the population had reached a dangerous level in winter 1914, a set of measures was devised with two aims: to recruit refugees increasingly for the labour market, and to provide cultural (school lessons, reading, writing and embroidery courses) and religious pastoral care. Jewish refugees were refused work permits to prevent them from settling permanently and to facilitate their immediate repatriation. They were able to find employment in Vienna almost exclusively as home workers.

Translation: Nick Somers

Hoffmann-Holter, Beatrix: „Abreisendmachung“. Jüdische Kriegsflüchtlinge in Wien 1914-1923, Wien/Köln/Weimar 1995

Hoffmann-Holter, Beatrix: Jüdische Kriegsflüchtlinge in Wien, in: Heiss, Gernot/Rathkolb, Oliver (Hrsg.): Asylland wider Willen. Flüchtlinge in Österreich im europäischen Kontext seit 1914, Wien 1995, 45-59

Kohlbauer-Fritz, Gabriele: „Elend, überall wohin man schaut“. Kriegsflüchtlinge in Wien, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 96-103

Mentzel, Walter: Weltkriegsflüchtlinge in Cisleithanien 1914-1918, in: Heiss, Gernot/Rathkolb, Oliver (Hrsg.): Asylland wider Willen. Flüchtlinge in Österreich im europäischen Kontext seit 1914, Wien 1995, 17-44

Quotes:

Refugees as "shameless intruders": Attitude of the population to refugees from Galicia, 20 June 1915, AVA, MdI, Präs., Sign. 19/3, Zl. 13241, quoted from: Mentzel, Walter: Weltkriegsflüchtlinge in Cisleithanien 1914-1918, in: Heiss, Gernot/Rathkolb, Oliver (Hrsg.): Asylland wider Willen. Flüchtlinge in Österreich im europäischen Kontext seit 1914, Wien 1995, 23 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- The growing city: Vienna on the eve of the First World Wa

- The war takes over the city

- Rebuilding for war: barracks and hospitals in Vienna

- Vienna as a refugee camp

- Vienna as a centre of the war economy

- Goodbye to the world of yesterday

- Self-help: unofficial allotments and deforesting the Vienna Woods

- Overthrow of the old values: post-war Vienna