With his national feudal views, Count István Tisza was a typical representative of the Hungarian gentry, who dominated Hungary’s political landscape around 1900. As Hungarian minister president, he cultivated an authoritarian style with distant loyalty to Vienna and an uncompromising attitude to the demands of ethnic minorities.

István Tisza (1861–1918) continued the political programme of his father Kálmán Tisza (1830–1902), who had been minister president of Hungary from 1875 to 1890. As head of the nationalist Liberal Party, which had the most votes, he became minister president in 1903 but resigned in 1905, when the Liberals suffered an election defeat and the radical nationalist extremists became the strongest party in the Hungary parliament. After the political crisis had been settled in 1905/06, he returned triumphantly in the 1910 elections. Tisza became the ‘strong man’ of Hungary and was able to continue his previous policies. He was an uncompromising representative of Magyar interests in the supranational state, which made him into a bitter opponent of the heir to the throne Archduke Franz Ferdinand, who sought to water down the special status of the Magyars established by the 1867 Compromise and to strengthen the central authority. Tisza also rejected an extension of federalism, which would have helped the smaller nations to obtain more autonomous rights.

Tisza’s dictatorial regime also influenced the political atmosphere in the first years of the First World War. Supporters of change in conservative Viennese circles looked enviously at Budapest. Thanks to his firm opposition to democratic tendencies, Tisza was also seen in Berlin as a more dependable partner than the government in Vienna, which had to be more open to compromise in view of the diverging interests of the various national groups.

Because of the more authoritarian style of government in Hungary, the situation did not change as radically as in Cisleithania after the outbreak of war in July 1914. Tisza managed to keep the influence of the army leadership on civilian affairs to a minimum. In contrast to the Austrian half of the empire, the Hungary parliament was also able to continue operating. This was due to the greater loyalty of the Magyar elite, who dominated the Hungary parliament, to the Hungarian state, while the Austrian government had become unpredictable because of the nationalist conflicts. Thanks to the protectionist economic policy, which was also applied to Cisleithania, and Hungary’s agricultural resources, shortages were less sharply felt than in Austria.

In his attitude to the war, Tisza always had Magyar interests uppermost in his mind. He was in favour of military action to counter Serbian and Romanian expansionist plans as a way of obstructing the national irredentism of the various minorities in Hungary, but contrary to the aspirations of the Austro-Hungarian military leadership he opposed the annexation of further territories in the Balkans, not least as the incorporation of additional regions with southern Slav or Romanian inhabitants would have further jeopardized the privileged status of the Magyars.

Tisza was able to influence the new King Karl and to persuade the young and politically inexperienced monarch in autumn 1916 to have himself crowned King of Hungary. In this way, Karl renounced the opportunity of reforming the Hungarian constitution, because by taking the coronation oath he committed himself to the provisions of the existing constitution, which favoured the Magyars.

The consequences of the rejection of the Magyarization policy by the non-Magyar language groups is illustrated by the invasion by Romanian troop of Transylvania after Romania’s declaration of war on Austria-Hungary in 1916. The Romanian units were welcomed by the Transylvanian Romanians as liberators from the Magyar yoke.

This prompted an increase in the resistance to Tisza’s dictatorial style. An opposition group led by the liberal aristocrat Count Mihály Károlyi (1875–1955) called for democratic reforms, universal suffrage and the federalization of Hungary. If Hungary was to survive in its historical borders, the national demands of ethnic minorities could no longer be ignored. Tisza’s authoritarian regime began to falter, and in June 1917 ‘Hungary’s strong man’ resigned.

Even after Tisza’s resignation, also because of the massive differences of opinion between him and the young emperor and Hungarian King Karl, he remained the dominant political figure. He was assassinated by Hungarian revolutionaries on 31 October 1918 as a symbol of the old regime.

Translation: Nick Somers

Hanák, Péter: Die Geschichte Ungarns. Von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart, Essen 1988

Hoensch, Jörg K.: Geschichte Ungarns 1867–1983, Stuttgart 1984

Lukacs, John: Ungarn in Europa. Budapest um die Jahrhundertwende, Berlin 1990

Markus, Adam: Die Geschichte des ungarischen Nationalismus, Frankfurt/Main u. a. 2013

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Tóth, István György (Hrsg.): Geschichte Ungarns, Budapest 2005

-

Chapters

- The Magyars and the Habsburg Monarchy

- From ‘Natio Hungarica’ to Magyar nation

- Pride of the nation: the Hungarian nobility

- The Hungarian war of independence 1848/49

- From neo-absolutism to Compromise

- Élyen a Magyar – long live the Magyars! Hungarian Magyarization policy

- The crisis of dualism

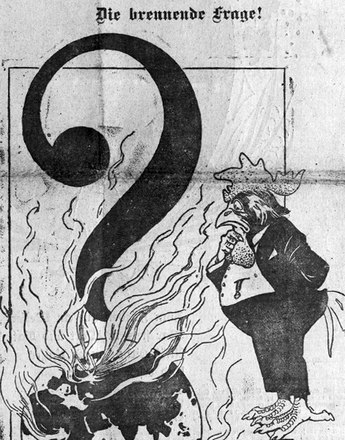

- István Graf Tisza: Hungary’s ‘strong man’