In view of the absence of social elites – the nobility in the Romanian settlement areas of the Habsburg Monarchy were Magyar, and the urban bourgeoisie Magyar and German with considerable Jewish, Greek and Armenian elements – the Romanian intelligentsia was recruited mainly from the clergy.

The first national awareness and concern about the Romanian language and history also came from the ranks of the priesthood. One prominent figure in this regard was the orthodox bishop and later Metropolitan Andreiu Șaguna (1809–73). He pioneered Romanian primary education as a way of combating the widespread illiteracy and initiated the first Romanian-speaking secondary schools in Transylvania. He also founded the newspaper Telegraful Român in 1853, which became an important mouthpiece of emerging Romanian nationhood.

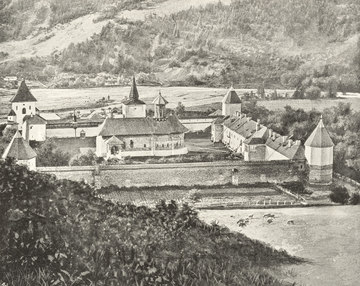

The traditions of the eastern Churches were the dominant cultural influence among the Romanians. Membership of the orthodox community in the Habsburg Monarchy was a way of setting themselves apart from the Hungarians and was increasingly seen as a sign of ‘genuine’ Romanianness.

An important role, particularly at the beginning of the nationhood process, was played by the Greek Catholic Church, although only a minority of Romanians belonged to it. As this Church, despite retaining the Byzantine rite, was part of the Roman Catholic Church, its members came into contact early on with western ideas. The Romanian united clergy also therefore advocated a written Romanian language, while the orthodox clergy remained for a long time influenced by the Greek and Slavic cultural tradition. Because of the strong influence of the Slavic liturgy, which was also used by Romanians in their worship, the Romanian intelligentsia originally used old Church Slavonic as literary language with Romanian texts being written in Cyrillic.

The use of the Latin alphabet was first justified with reference to the descent from the ancient Dacians and hence the fact that Romanian was in fact a Romance language. In the eighteenth century the theory of Daco-Romanian continuity was proposed by the united clergy of Transylvania as an expression of their search for historical roots as a component of the national identity. In keeping with this idea and as a deliberate break with the earlier eastern traditions, the Latin alphabet was decreed in the young Romanian nation state in 1860 for official texts.

Translation: Nick Somers

Hanák, Péter: Die Geschichte Ungarns. Von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart, Essen 1988

Hitchins, Keith: Die Rumänen, in: Wandruszka, Adam/Urbanitsch, Peter (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, Band III: Die Völker des Reiches, Wien 1980, Teilband 1, 585–625

Hoensch, Jörg K.: Geschichte Ungarns 1867–1983, Stuttgart 1984

Hösch, Edgar: Geschichte der Balkanländer. Von der Frühzeit bis zur Gegenwart, München 1999

Kahl, Thede: Rumänien. Band 1: Raum und Bevölkerung. Geschichte und Geschichtsbilder (= Österreichische Osthefte 48), Wien 2008

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005