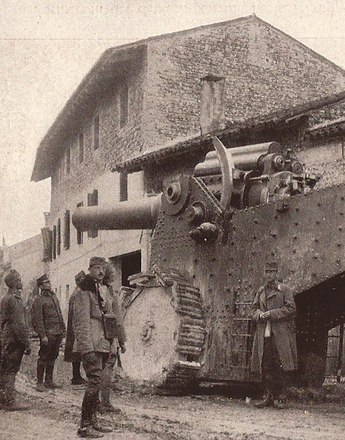

Modern weaponry and the slaughter of the first months of the war

The modern weaponry available to the belligerents caused heavy casualties in offensive conducted by the Austro-Hungarian high command on the Russian and Serbian fronts in the first months of the war. There were no preparations at the front or behind the lines for the masses of wounded troops and officers.

Most of the military commanders of the belligerent nations had received their training in the last third of the nineteenth century. Austria-Hungary was no exception. Commander-in-chief Field Marshal Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf (1852–1925), the “emperor’s falcon”, and Oskar Potiorek, who led the Austro-Hungarian army in the disastrous first phase of the war against Serbia in the Balkans, were both over sixty years old. They opted for an offensive tactic that was hopelessly outdated in view of the modern weapons available. As a result, large numbers of Austro-Hungarian and enemy soldiers and officers were killed in the first battles on the Russian and Serbian fronts. Some committed suicide, and many were transported back to Vienna with bullet wounds and other injuries.

By the end of August 1914, over a quarter of a million wounded troops had been sent back to Vienna. Officers and soldiers died from their severe wounds in Viennese hospitals and clinics. The first of many was the 26-year-old infantryman Alois Newrzival, who died of a bullet wound in the General Hospital on 7 September 1914. On the same day, the 28-year-old Russian infantryman Andreas Lapschin succumbed to his wounds in Jubiläumsspital in the 13th district. The first Viennese soldier to die in a Viennese hospital was the 22-year-old labourer Josef Michalatsch, who committed suicide in Rudolfspital on 26 September 1914.

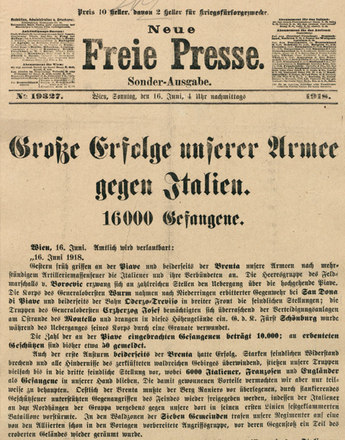

A very large number of officers and men died in the first months of the war, but that was just the beginning. The Isonzo campaign, the South Tyrol offensive in spring 1916, the Russian Brusilov offensive, and the last offensive of the Austro-Hungarian army in June 1918 on the Piave also caused heavy losses.

Altogether around 22,000 soldiers died in Vienna during the First World War. The casualty rates were particularly high in November and December 1914, April to October 1917 and in the last year of the war. Towards the end of the war the main cause of death was no longer bullet wounds but diseases – a small typhoid fever and smallpox epidemic in autumn 1914 and winter 1914–15, a dysentery epidemic in 1917, and then – not directly connected with the war but probably caused by US soldiers –Spanish Flu and pneumonia. One prominent victim was the painter and noncombatant Egon Schiele, who died in Vienna at the end of October 1918, a few days after his wife.

Translation: Nick Somers

Magistrat der Stadt Wien: Statistische Mitteilungen, Monatsberichte 1914–1918

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2013

Rosenfeld, Siegfried: Die Wirkung des Krieges auf die Sterblichkeit in Wien, Wien 1920

Weigl, Andreas: Eine Stadt stirbt nicht so schnell. Demographische Fieberkurven am Rande des Abgrunds, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 62-71

-

Chapters

- Modern weaponry and the slaughter of the first months of the war

- Hospital capacities, epidemic service and the rapid shortage of skilled medical staff

- Emergency hospitals in Vienna

- The university and other temporary hospitals

- Künstlerhaus and Secession as temporary war hospitals

- Wounded transports, food and care

- Cured and well-fed for the war