Hospital capacities, epidemic service and the rapid shortage of skilled medical staff

Vienna had an impressive peacetime hospital infrastructure. For the countless wounded and sick soldiers, a quarter of a million of them, sent to Vienna, however, the capacities were woefully inadequate. To make matters worse, there was very soon a shortage of skilled doctors, many of whom had been conscripted into the army in spite of their importance as medical practitioners.

As in so many areas, the hospital infrastructure in the Habsburg monarchy was in no way adequate for a world war. It quickly became evident that there were not enough beds for the wounded soldiers coming back from the front to Vienna. There was also an immediate shortage of doctors and skilled nursing personnel. As the army high command, which had completely misjudged the situation, was counting on a rapid military victory, they conscripted medical personnel without any consideration for their vital importance on the home front. Many of the doctors sent to the front early in the war were also wounded, killed or captured. Medical students were therefore trained for “epidemic service” and doctors were sought amongst the refugees from Galicia and Bukovina. Women doctors also had new opportunities as a result of the war, although they often had to cede their positions again at the end of 1918 to the returning “war doctors”.

In 1914 there were thirty-eight hospitals with around 8,600 beds, although 600 of them were in children’s hospitals. Added to this were six psychiatric institutes with around 2,500 beds and seven convalescent homes, making a total of almost 13,000 beds. The main burden was born by the nine state hospitals, including the General Hospital, Kaiser-Franz-Joseph-Spital, Krankenanstalt Rudolfstiftung and Wilhelminenspital. These hospitals had around 6,450 beds.

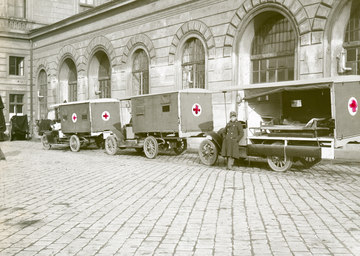

These beds were urgently required, because from 24 August 1914 onwards masses of wounded soldiers were arriving in Vienna every day. They were treated there to make them “fit for duty” or “fit for employment” as civilians. Based on the number of wounded and sick soldiers transported on special trains, the figures peaked in 1916–17 with over 300,000 patients, but hospital capacities remained overstretched right through to the end of the war and afterwards.

Right after the outbreak of war, around 7,000 beds were reserved for military personnel to the detriment of civilian patients. Even so, this fell far short of the needs of the military. During the war some large hospitals had twice as many patients as beds.

Translation: Nick Somers

Biwald, Brigitte: Von Helden und Krüppeln. Das österreichisch-ungarische Militärsanitätswesen im Ersten Weltkrieg (Militärgeschichtliche Dissertationen österreichischer Universitäten 14/2), Wien 2002

Biwald, Brigitte: Krieg und Gesundheitswesen, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 294–301

Hofer, Hans-Georg: Mobilisierte Medizin. Der Erste Weltkrieg und die Wiener Ärzteschaft, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 302–309

Pawlowsky, Verena/Wendelin, Harald: Der Krieg und seine Opfer. Kriegsbeschädigte in Wien, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 310–317

Weigl, Andreas: Mangel – Hunger – Tod. Die Wiener Bevölkerung und die Folgen des Ersten Weltkriegs (Veröffentlichungen des Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchivs Reihe B: Heft 90), Wien 2014

-

Chapters

- Modern weaponry and the slaughter of the first months of the war

- Hospital capacities, epidemic service and the rapid shortage of skilled medical staff

- Emergency hospitals in Vienna

- The university and other temporary hospitals

- Künstlerhaus and Secession as temporary war hospitals

- Wounded transports, food and care

- Cured and well-fed for the war