Provisioning the Troops – shortages, surrogates and hunger

-

“Field bakery”, photo 1914/15

Copyright: Josef Neubauer

-

“Travelling field kitchen”, photo 1914/15

Copyright: Josef Neubauer

-

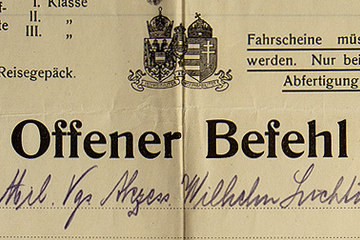

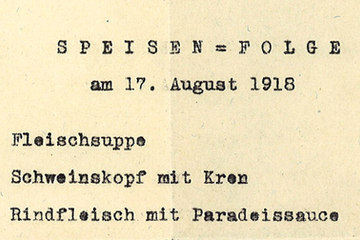

Officers’ menu, 1918

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

Provisioning on the front and at home was one of the central topics in the Feldpost (military postal service) correspondence of officers and troopers alike. It contains questions and worries about the adequate nourishment of the families at home, likewise recurring requests for food, tobacco, fresh underwear, warm clothes, boots and so forth. Meanwhile the letters were dominated by detailed descriptions of the daily bill o’ fare and the portions and rations. Above all, as the four war years wore on, the correspondence of the normal troopers increasingly featured descriptions of shortages, the poor quality of the food, and of hunger.

One of the main objectives of the Austrian-Hungarian military establishment was to preserve the soldiers’ physical and mental ‘fighting spirit’. To ensure this they should be provided ideally with sufficient and richly varied food. This immediately foundered not least on the military principle prescribing that troop provisioning was to be primarily managed from the surrounding scene of operations. This meant that provisioning was greatly dependent on the respective scene of military operations, which brought with it very different situations in catering for needs.

It was planned in principle to set up provisioning stations on each scene of military operations, which would supply food, building material and heating fuel to the troops in mobile carts. For instance, Isabelle Brandauer has shown that “for the one-day provisioning of one infantry division around 40 tons of naturalia […] were needed, requiring for their transport 50 to 100 cartloads, depending on the type of cart available.” When this daily quota was used up, replacement and requisitioning, according to Brandauer, was accomplished firstly through on-site requisitioning, secondly, supplies came from mobile provisioning equipment or by rail. Meat and bread, foods which could be preserved only for a short time, were primarily acquired through requisitioning or purchase on site. As an alternative, mobile baking ovens were used, which made fresh bread; the high-altitude positions on the Southwestern Front were provided for by so-called mountain ovens.

When troops were on the move they were followed in the “Trainbereich” (incl. transport, supply, medical and postal elements) by mobile field kitchens. These were usually drawn by horses and could “feed a troop of 250 persons”. However, the cumbersome supply services were often held up, hindered by muddy ground softened by rain, by snow or ice.

The high altitude positions on the Southwestern Front often lay at over 9,000 feet (the highest gun position was on the Ortler at over 12,000 feet). Cableways, bridle paths and carriers were used to provide the soldiers in these positions with food, clothing and ammunition. The fatiguing and energy-sapping drag to the summits was worsened in winter, with its heavy snowfalls, or also in spring, with its thaws, avalanches, floods and mudslides. The ascent and transportation were therefore often impossible or only managed at high risk and the danger of being buried alive or killed.

The provisioning problems exacerbated by the geographical and climatic conditions in the Mountain War is captured in the description of the soldier Josef Mittermaier, deployed on Monte Cristallo in the Dolomites: “The rations could only be brought around or after midnight; a cold, stinking meat soup with usually poorly boiled, ragged piece of meat, half a round of hard bread; sometimes a bit of cold wiry stuff, which we called sauerkraut or what was supposed to be sauerkraut. For the morning there was a drop of surrogate coffee; rumour had it that it was made of crushed beetles, horse dung, roasted hay husks and a bit of sugar. And cold water in the field flask.”

As the war wore on, food had to be supplemented with surrogates or entirely substituted with them, which made much of it inedible. But they were also put on the soldiers’ bill o’ fare, just as was spoiled or mildewed food. Moreover, there were frequent bottlenecks in provisioning food, so that hunger was often the only item on the daily menu.

The lack of food and provisions for the troopers also had negative effects on their health. As Elisabeth Dietrich observes, cases of undernourishment accumulated, not surprising considering the daily ration in spring 1918 of “half a tin of preserved meat, dry vegetables and a lump of maize as bread.” Thus the average weight of soldiers by the end of the war was no more than 55 kilograms.

The thematic complex relating to “Food and Provisioning” also draws attention to the yawning class differences between the troopers and their superior officers; a menu from the officers’ mess of the Imperial-Royal 24 cm Canon Battery still boasted in August 1918 “meat soup, roast beef and roast pork”, also “chocolate, compote, biscuits and coffee”.

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Biwald, Brigitte: Von Helden und Krüppeln. Das österreichisch-ungarische Militärsanitätswesen im Ersten Weltkrieg, Teil 2, Wien 2002

Brandauer, Isabelle: Menschenmaterial Soldat. Alltagsleben an der Dolomitenfront im Ersten Weltkrieg 1915–1917, Innsbruck 2007

Dietrich, Elisabeth: Der andere Tod. Seuchen, Volkskrankheiten, und Gesundheitswesen im ersten Weltkrieg, in: Eisterer, Klaus/Steininger, Rolf (Hrsg.): Tirol und der Erste Weltkrieg, Innsbruck/Wien 1995, 255–275

Hämmerle, Christa: Soldaten, in: Labanca, Nicola/Überegger, Oswald (Hrsg.): Krieg in den Alpen. Österreich-Ungarn und Italien im Krieg, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2014, im Druck

Quotes:

„This immediately foundered ...“: Brandauer, Isabelle: Menschenmaterial Soldat. Alltagsleben an der Dolomitenfront im Ersten Weltkrieg 1915–1917, Innsbruck 2007, 204

„for the one-day provisioning …“: quoted from: Brandauer, Isabelle: Menschenmaterial Soldat. Alltagsleben an der Dolomitenfront im Ersten Weltkrieg 1915–1917, Innsbruck 2007, 205

„When this daily quota was used up …“: Brandauer, Isabelle: Menschenmaterial Soldat. Alltagsleben an der Dolomitenfront im Ersten Weltkrieg 1915–1917, Innsbruck 2007, 205

„Meat and bread, foods …“: Brandauer, Isabelle: Menschenmaterial Soldat. Alltagsleben an der Dolomitenfront im Ersten Weltkrieg 1915–1917, Innsbruck 2007, 206-208

„feed a troop of 250 persons …“: quoted from: Brandauer, Isabelle: Menschenmaterial Soldat. Alltagsleben an der Dolomitenfront im Ersten Weltkrieg 1915–1917, Innsbruck 2007, 208

„The rations could only be brought ...“: Mittermaier, Johann: Der Schrecken des Krieges. Die Erinnerungen eines Südtiroler Kaiserjägers aus dem 1. Weltkrieg, Brixen 2005, 74, quoted from: Brandauer, Isabelle: Menschenmaterial Soldat. Alltagsleben an der Dolomitenfront im Ersten Weltkrieg 1915–1917, Innsbruck 2007, 219

„half a tin of preserved meat, ...“: quoted from: Dietrich, Elisabeth: Der andere Tod. Seuchen, Volkskrankheiten, und Gesundheitswesen im ersten Weltkrieg, in: Eisterer, Klaus/Steininger, Rolf (Hrsg.): Tirol und der Erste Weltkrieg, Innsbruck/Wien 1995, 265

„Thus the average weight …“: Dietrich, Elisabeth: Der andere Tod. Seuchen, Volkskrankheiten, und Gesundheitswesen im ersten Weltkrieg, in: Eisterer, Klaus/Steininger, Rolf (Hrsg.): Tirol und der Erste Weltkrieg, Innsbruck/Wien 1995, 265

„meat soup, roast beef and ...“: Leopold Wolf, Offiziers-Messe. Speisen-Folge, 17. August 1918, Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Nachlass 14, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien