One of first momentous experiences for the recruits was saying farewell to their families and relatives at home-town railway stations throughout the Monarchy.

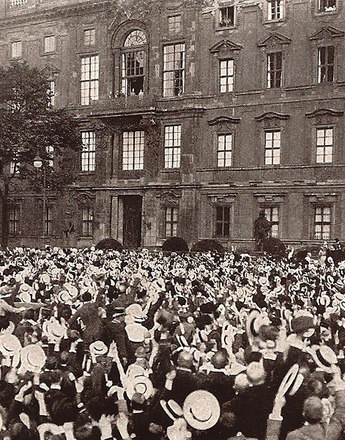

Countless photographs have been preserved, and as we look we are struck by the recurring motifs. They are of departing soldiers, leaning out of the railway wagons, smiling at the camera, but some with earnest glances, or staring at the crowds of people who have gathered at the stations to say goodbye as they leave. ‘Jubilant gestures’, flowers, food, drinks and small presents dominated the “railway station experience” at the start of the war, which, as the historian Oswald Überegger points out, “will remain in the memories of the population as an inspired farewell scenario, and it ought indeed to remain in their memories.”

Remote from this public, highly atmospheric scene conveying such propagandist fervour, the moods and feelings of the soldiers on their way to the front were of course more complex.

Although not a few of them were infected and thrilled by the public jubilation and “station hysteria”, as Überegger calls it, nevertheless, the farewells from their loved ones at home and the uncertain future aroused thoughts in many of them that were equally troubled and negative – the fear of the unknown war and what was to be expected.

Studies on everyday life, experience and local history proved that the much propagated, class-transcending “war fever” of the population in summer 1914 – also uncritically accepted for a long time by historians – must be scrutinised with more discrimination. The start of the war was marked far more, to quote Oswald Überegger again, by a “co-existence of inspired and non-affirmative interpretative patterns as regards the war, extremes which were overridden by a broad spectrum of neither-nor patterns of behaviour, best expressed in the terms ‘readiness for war’, ‘passive acceptance of war’ and ‘fulfilment of duty’”.

We can best observe how varied the events and experiences are inscribed into the soldiers’ narratives about their mobilisation in two examples, one related by a Tyrolean Kaiserjäger – a member of the Alpine Corps – and a countryman from Trent. Their descriptions of the farewells at the station and the forthcoming way to the front are very different. The Tyrolean Kaiserjäger Matthias Ladurner-Parthanes noted down in his diary: “At every station it was the same: waving and shouting, handshakes, people bringing things to eat and drink; especially the latter were lavishly enjoyed, so much so that at a short distance from the last station the ones who had had too much of a good thing were calling on Saint Ulrich as patron saint of stomach pains.”

The diary entry of the Trent countryman Giovanni Zontini is something else altogether; it is less about the general euphoria than the threatening uncertainty of his own future. “The train was adorned with flowers, garlands and flags, but thoughts were sombre, death didn’t seem far away. The songs were sad, as sad as birds on snow.”

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Heiss, Hans: Andere Fronten. Volksstimmung und Volkserfahrung in Tirol während des Ersten Weltkrieges, in: Eisterer, Klaus/Steininger, Rolf (Hrsg.): Tirol und der Erste Weltkrieg, Innsbruck/Wien 1995

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Kriegermentalitäten. Mistzellen aus Österreich-Ungarns letztem Krieg, in: Dornik, Wolfram/Walleczek-Fritz, Julia/Wedrac, Stefan (Hrsg.): Frontwechsel. Österreich-Ungarns „Großer Krieg“ im Vergleich, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2014

Überegger, Oswald: Der andere Krieg. Die Tiroler Militärgerichtsbarkeit im Ersten Weltkrieg, Innsbruck 2002

Quotes:

„will remain in the memories ...“: quoted from: Überegger, Oswald: Der andere Krieg. Die Tiroler Militärgerichtsbarkeit im Ersten Weltkrieg, Innsbruck 2002, 259

„station hysteria“: quoted from: Überegger, Oswald: Der andere Krieg. Die Tiroler Militärgerichtsbarkeit im Ersten Weltkrieg, Innsbruck 2002, 259

„co-existence of inspired and non-affirmative ...“: quoted from: Überegger, Oswald: Der andere Krieg. Die Tiroler Militärgerichtsbarkeit im Ersten Weltkrieg, Innsbruck 2002, 258

„At every station it was the same: ...“: Matthias Ladurner-Parthanes, quoted from: Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Kriegermentalitäten. Mistzellen aus Österreich-Ungarns letztem Krieg, in: Dornik, Wolfram/Walleczek-Fritz, Julia/Wedrac, Stefan (Hrsg.): Frontwechsel. Österreich-Ungarns „Großer Krieg“ im Vergleich, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2014, 52

„The train was adorned with flowers ...“: Giovanni Zontini, quoted from: Heiss, Hans: Andere Fronten. Volksstimmung und Volkserfahrung in Tirol während des Ersten Weltkrieges, in: Eisterer, Klaus/Steininger, Rolf (Hrsg.): Tirol und der Erste Weltkrieg, Innsbruck/Wien 1995, 145