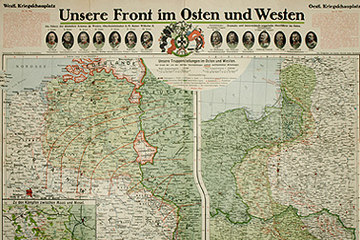

During the First World War the relationship between troopers and officers was marked by great class differences and the conflicts this generated. Within the ranks as well, tensions flared up time and again, often because of the predominant mix of nationalities in the Monarchy Army.

Someone might be ‘Czech’, ‘Bohemian’ or ‘Tyrolean’; he might be a mechanic in civilian life and ordered around by someone he saw as an inferior in relation to his own occupation; he might be a farmer who gets “home leave” because he had to help in bringing in the harvest at home – all these situations caused tensions and conflicts among the soldiers. Stereotype ideas, prejudices, and the feeling of being treated unjustly played just as much a role as the continuation of hierarchies and power relations in civil society.

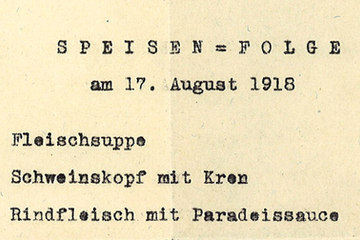

Military hierarchy systems and the blatant class consciousness of the officers of the Imperial-Royal Army often led to a extremely conflict-laden relationship between the ranks and their superiors – often resulting in genuine “officer hatred”. Unjust treatment, discrimination and verbal abuse contributed to this, likewise physical and mental ill-treatment. Added to this was the goad of seeing preferential treatment and privileged positions granted to the officers with regard to provisioning and billeting.

So-called “Frontsekkiererei” – teasing and chicanery – as the soldiers often termed the power of command of their superior officers and charges, was also, according to Oswald Überegger, “one of the most frequent causes of violations of duty and obedience, which were usually limited to mere refusal, but (…) also escalated into actions.”

In a diary entry written by the officer’s representative Hartinger of 30 January 1917, we can read the following: “Today was a gr. Court day. A patrol consisting of 1 corporal and 2 men (listening-post sentries) refused to go to their posts at night, and the corporal declared he was the father of 7 children and was not going put his life at stake recklessly for the whim of the commanding officer. The man was tethered in the trench for two hours. I’m boiling with rage. The men are asked to go out there, out of their safe shelter in all conditions, while so many officers, utterly convinced of how indispensible they are, cannot be induced even once to have a look at their men’s position.”

Physical punishments, so-called “Leibstrafen”, were still customary in the Imperial-Royal Army during the First World War – they might be imposed for “the slightest infringements of discipline” such as soiled plates and cutlery or eating a reserve portion. The physical punishment for such ‘offences’ ranged from “Anbinden” – tethering – to so-called “Schliessen in Spangen” – shackling.

The possible catastrophic effects for instance of “Anbinden” for the soldiers in winter in freezing temperatures and snow are noted down in his diary by the Kaiserjäger Franz Huter in February 1915: “We kept having to fall in, (…). Two Viennese men who had eaten up their reserve portions were tied up for two hours. When they were released they both fell over. Their feet were frozen. A fortnight later we got the news from the field hospital that both men had to have their feet amputated.”

It was not until March 1917 that Emperor Karl ordered “Anbinden” to be eliminated from the army penal code. Finally, in June 1917, “Schliessen in Spangen” was also prohibited. But, Christa Hämmerle observes, this prohibition was reversed already in 1918 because of the soldiers’ accumulating refusals to serve and obey.

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Biwald, Brigitte: Von Helden und Krüppeln. Das österreichisch-ungarische Militärsanitätswesen im Ersten Weltkrieg, Teil 2, Wien 2002

Brandauer, Isabelle: Menschenmaterial Soldat. Alltagsleben an der Dolomitenfront im Ersten Weltkrieg 1915–1917, Innsbruck 2007

Hämmerle, Christa: „…dort wurden wir dressiert und sekkiert und geschlagen…“ Vom Drill, dem Disziplinarstrafrecht und Soldatenmisshandlungen im Heer (1868 bis 1914), in: Cole, Laurence/Hämmerle, Christa/Scheutz, Martin (Hg.): Glanz, Gewalt, Gehorsam. Militär und Gesellschaft in der Habsburgermonarchie (1880 bis 1918), Essen 2011, 31-54

Hämmerle, Christa: Soldaten, in: Labanca, Nicola/Überegger, Oswald (Hrsg.): Krieg in den Alpen. Österreich-Ungarn und Italien im Krieg, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2014, im Druck

Hanisch, Ernst: Männlichkeiten: eine andere Geschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts, Wien 2005

Hautmann, Hans: Sittenbilder aus dem Hause Habsburg im Weltkriege, in: Ders.: Von der Permanenz des Klassenkampfes und den Schurkereien der Mächtigen. Aufsätze und Referate für die Alfred Klahr Gesellschaft, Wien 2013. Unter: http://www.klahrgesellschaft.at/Mitteilungen/Hautmann_2_08.pdf (23.06.2014)

Überegger, Oswald: Der andere Krieg. Die Tiroler Militärgerichtsbarkeit im Ersten Weltkrieg, Innsbruck 2002

Ziemann, Benjamin: Front und Heimat. Ländliche Kriegserfahrungen im südlichen Bayern 1914 – 1923, Essen 1997

Quotes:

„Someone might be ‘Czech’, …“: Brandauer, Isabelle: Menschenmaterial Soldat. Alltagsleben an der Dolomitenfront im Ersten Weltkrieg 1915–1917, Innsbruck 2007, 109

„Frontsekkiererei“: quoted from: Überegger, Oswald: Der andere Krieg. Die Tiroler Militärgerichtsbarkeit im Ersten Weltkrieg, Innsbruck 2002, 310

„one of the most frequent ....“: quoted from: Überegger, Oswald: Der andere Krieg. Die Tiroler Militärgerichtsbarkeit im Ersten Weltkrieg, Innsbruck 2002, 310

„Today was a gr. Court day ...“: Kriegsarchiv (KA) – War Archive, Nachlässe B/428, 224: Hartinger, 30.01.1917, quoted from: Hanisch, Ernst: Männlichkeiten: eine andere Geschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts, Wien 2005, 39

„the slightest infringements ...“ : quoted from: Hautmann, Hans: Sittenbilder aus dem Hause Habsburg im Weltkriege, in: Ders.: Von der Permanenz des Klassenkampfes und den Schurkereien der Mächtigen. Aufsätze und Referate für die Alfred Klahr Gesellschaft, Wien 2013. Unter: http://www.klahrgesellschaft.at/Mitteilungen/Hautmann_2_08.pdf, S. 13 (23.06.2014)

„We kept having to fall ….“: Huter, Franz: Kaiserjägertagebuch, pp. 34–95, quotes from: Biwald, Brigitte: Von Helden und Krüppeln. Das österreichisch-ungarische Militärsanitätswesen im Ersten Weltkrieg, Teil 2, Wien 2002, 356

„(...) this prohibition was reversed ...“: Hämmerle, Christa: Soldaten, in: Labanca, Nicola/Überegger, Oswald (Hrsg.): Krieg in den Alpen. Österreich-Ungarn und Italien im Krieg, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2014, in the press