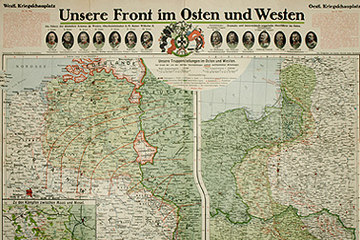

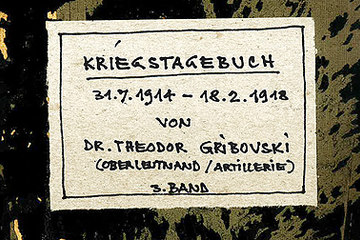

At the beginning of May 1915, the Russian front began to totter as a result of the German-Austrian breakthrough near Tarnów-Gorlice. Galicia, which had been occupied by the troops of Tsar Nicholas II, was reclaimed after just a few weeks. The ensuing forays by the German High Command in the East led to the conquest of Russian Poland and parts of the Baltic States.

Despite the fact that in the ‘East’ there were usually fewer troops and weapons, for a short period of time the highest firepower of the entire First World War was concentrated in this area. In the spring of 1915 the Central Powers of Germany and Austro-Hungary employed 334 heavy guns against just four on the Russian side as well as 1,272 field guns against 675 of the Russians. In addition there were the weak defence lines of the Tsarist Army: the fortifications turned out to be insufficient, the trenches afforded hardly any protection and there was no effective staggered defence to speak of.

These inadequacies and deficiencies led to an unprecedented offensive success on the part of the allied armies of the Habsburgs and Hohenzollern. On June 3 and June 22, 1915 they reclaimed Przemyśl and Lviv respectively; on August 5, German troops marched into Warsaw, in the middle of the month they crossed over the Bug River and by the end of the month had taken the fortified cities of Grodno and Brest-Litovsk.

In the course of these military operations, the Tsarist armed forces lost over 1.4 million soldiers, half of which were taken prisoner of war. At the same time the Russian retreat increased the Tsarist Army's problem of resources. On the one hand the Central Powers captured 1,300 guns, 53,000 heavy-calibre and approximately 800,000 field artillery shells; on the other the problem of lack of weaponry proved insoluble due to the loss of armament factories. Important industrial plants along the Western peripheral regions of the Tsarist Empire had been taken by the enemy; also the evacuation and dismantlement of factories were either not carried out in time or proved inadequate.

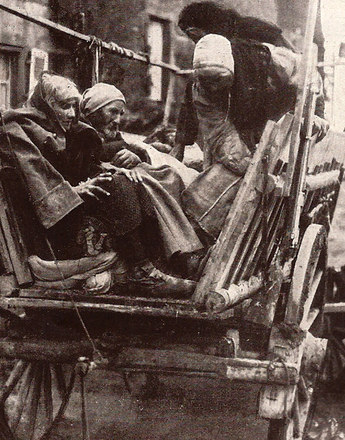

Apart from that, there was the Tsarist Army Commanders’ calculated ‘policy of scorched earth’; these acts of destruction were often accompanied by violence against ‘unreliable elements’. In addition, a wave of refugees arose which confronted even regions further away in the east of the Tsarist Empire with considerable problems both organisational and social in nature.

Herwig, Holger H.: The First World War. Germany and Austria-Hungary 1914–1918, London/New York/Sydney 1997

Stevenson, David: 1914–1918. The History of the First World War, London/New York 2004

Strachan, Hew: Der Erste Weltkrieg. Eine neue illustrierte Geschichte, 3. Auflage, München 2009

-

Chapters

- ‘The Forgotten Front’ – The Long Neglect and New Interest in the ‘East’

- Characteristics in Warfare at the Russian Front

- The Results of the Offensives and Territorial Gains

- War against the Local Population

- The Opening Military Campaigns

- The Calamity of the Tsarist Army

- Russia’s ‘Last Gasp’

- The Russian Revolution and the Fragile Peace in the ‘East’

- Occupation

- Never Ending Violence