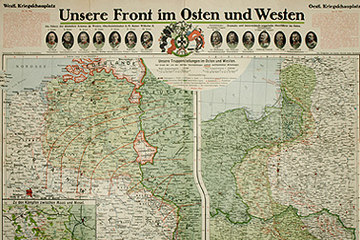

Neither Germany, nor Austria-Hungary nor Russia managed to create any kind of stable order for a shorter or longer period of time in the conquered territories, nor did they manage to bond with the local population for any longer period of time. This applied in varying grades of intensity and forms for nearly all territories concerned, with Poland, the Ukraine and the Baltic States leading the way.

The negative character of nearly all the experiences of occupation was based mainly on the growing economic crises and increasing supply shortfalls. For example, food rations in the entire Russian-Polish occupied territories – which were divided into a German and Austro-Hungarian General Government – dropped from more than 3,000 calories per capita before 1914 to 891 in the spring of 1918.

However, these developments did not vary significantly from the situation in areas of high population density and the capitals of the Danube Monarchy and the Hohenzollern and Tsarist Empires. Significantly, the Austrian Emperor Charles did not fail to make dramatic appeals when he entrusted some of his generals with the economic exploitation of occupied Ukraine in the spring of 1918. Declaring that the ‘continuation of the war’ was dependent upon it, Charles demanded ‘ruthless’, possibly forcible ‘requisitions’.

However, with or without ‘forceful appearance’, the Central Powers clearly missed their target. It already emerged in the summer of 1918 that the results of endeavours to organise better food supplies fell short of expectations. Instead of the agreed 200,000 heads of cattle that were to be delivered until July 31, only 91,000 were received. The incongruity was even more blatant when it came to grain and animal feed. Vienna and Berlin expected around one million tons of provisions from the so-called ‘Bread Peace’ with the Kiev government. As a matter of fact only 138,000 tons were loaded until December 23, 1918, whereof only 129,000 passed the border and ultimately only 49,000 tons reached the German Empire.

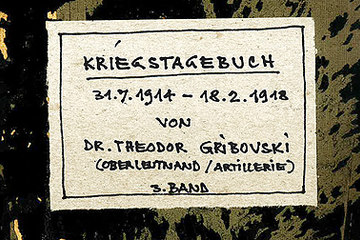

Added to the disappointing results concerning the economy were the sobering experiences of the occupying forces with opposing locals, pro-Soviet forces, and remnants of the Tsarist Army or ethnic groups that were hostile. In particular, rebellions and ‘anti-Bolshevik campaigns’ ended in guerrilla warfare and in various rearguard battles with the fleeing ‘Red Army’. Despite the fact that Ukraine belonged to one of the ‘occupied friendly states’ and efforts were made to solicit the sympathies of the local population, the relationship with the people ultimately remained distanced. The relationship between the occupying forces and the locals was not much different to the north and north-east of the Warsaw General Government – in those multi-ethnic territories that were named ‘Upper East’ in reference to the title of the commander of all Hohenzollern troops on the Eastern front, as well as in those parts of Galicia that had been under Russian control at the outbreak of hostilities.

Dornik, Wolfram et al.: Die Ukraine zwischen Selbstbestimmung und Fremdherrschaft 1917–1922, Graz 2011

Hagen, Mark von: War in a European Borderland. Occupations and Occupation Plans in Galicia and Ukraine, 1914–1918, Seattle/London 2007

Liulevicius, Vejas Gabriel: Kriegsland im Osten. Eroberung, Kolonisierung und Militärherrschaft im Ersten Weltkrieg, Hamburg 2002

Scheer, Tamara: Zwischen Front und Heimat. Österreich-Ungarns Militärverwaltungen im Ersten Weltkrieg, Frankfurt am Main 2009

-

Chapters

- ‘The Forgotten Front’ – The Long Neglect and New Interest in the ‘East’

- Characteristics in Warfare at the Russian Front

- The Results of the Offensives and Territorial Gains

- War against the Local Population

- The Opening Military Campaigns

- The Calamity of the Tsarist Army

- Russia’s ‘Last Gasp’

- The Russian Revolution and the Fragile Peace in the ‘East’

- Occupation

- Never Ending Violence