Hannes Leidinger

The Italian Front

Austria and Italy at the End of the First World War and in the Post-war Years

The seriously damaged relations between both countries improved to some extent only in view of later ambitions of an ideological and power-political nature. The fascist government of Benito Mussolini, which endeavoured to exert influence in the Danubian region and in so doing supported in particular authoritarian regimes, anti-socialist and anti-marxist movements, was regarded with ongoing suspicion in Austria, however. Resentment towards the ‘contract-breaching, unreliable and treacherous neighbours’ was even heightened in view of the threat to the ‘austro-fascist corporate state’ from the National Socialist German Empire.

Italy as Victorious Power in Austria

In September 1918 defeat was inevitable for the Central Powers. On the western front the German troops were no longer able to launch a decisive offensive, while on the Balkans Bulgaria requested a ceasefire. While the highest army command in Germany even reckoned with negotiations with the Allies, the Danube Monarchy disintegrated within a few days at the end of October. Aware that territorial gains in the last few weeks of the war could affect future peace agreements, Italy attacked at Vittorio Veneto on October 23.

War at Sea

While Germany made use of the Austro-Hungarian naval bases on the Adria for the deployment of submarines, this part of the Mediterranean remained merely a sideshow for most countries.

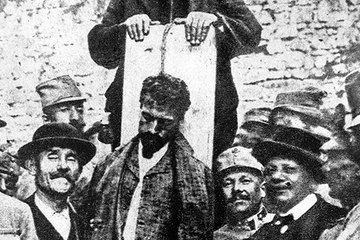

Pyrrhic Victory and Failure on the Isonzo

After orders were refused among his military units, Italy’s Chief of Staff Luigi Cadorna realised that the soldiers needed a break. Yet his measures gave the impression after the eleventh Isonzo battle (mid-August to mid-September 1917) that he would soon go back on the offensive. Adequate defence positions were dispensed with. All guns remained on the foremost front line.

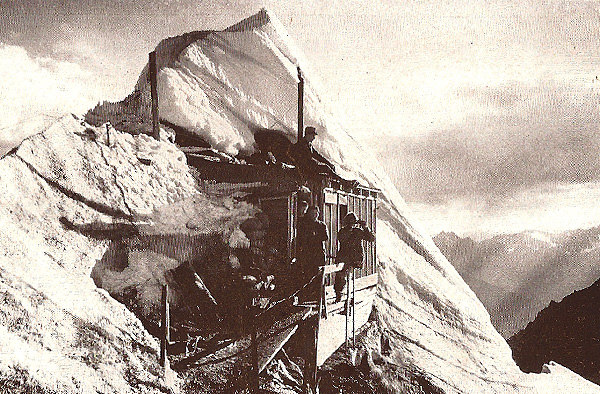

The Tyrolean Front

In the plains of Russia and France many offensives ground to a halt – the mountain war in the Alps was inherently bound to sometimes insuperable topographical and climatic obstacles, especially for those attacking.

On the Isonzo

Pessimism prevailed in the Habsburg Empire after the declaration of war by Italy. Many were convinced that the developments on the new Southwest Front would develop within a few weeks into a catastrophe. Chief of Staff Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf expected the enemy in the south to attack the Danube Monarchy area soon on account of its numerical superiority.

The Path to War

In order to keep Italy on the side of its Triple Alliance partners, or at least to ensure the neutrality of the Apennine Kingdom, territorial cessions were on table from the outset. But the Entente also wanted to secure the goodwill of the Roman government using this method. So began the manoeuvring and haggling for the most favourable conditions and alliances.

Neutrality – Differences of Opinion in the Apennine Kingdom

Between August 1914 and May 1915 heated debates took place in Italy on the country’s stance towards the emerging ‘peoples’ struggle’. Wherever one looked, opposing opinions on whether to enter the war were to be found at conferences and assemblies, in newspaper articles and proclamations, on demonstrations and marches.