In September 1918 defeat was inevitable for the Central Powers. On the western front the German troops were no longer able to launch a decisive offensive, while on the Balkans Bulgaria requested a ceasefire. While the highest army command in Germany even reckoned with negotiations with the Allies, the Danube Monarchy disintegrated within a few days at the end of October. Aware that territorial gains in the last few weeks of the war could affect future peace agreements, Italy attacked at Vittorio Veneto on October 23.

For five days the Austro-Hungarian troops resisted, then they dissolved. The attempt by Emperor Charles to reshape the empire on a federal basis accelerated the disintegration process. The Czechoslovakian and South Slavic states came into being, Galicia tended towards the resurrected Poland, while in Vienna and Budapest national governments were established with the fall of the empire. Significantly, the Magyars considered the matters surrounding the collapsing Habsburg Empire as no longer their concern.

Without the participation of Hungary, the army command of the Dual Monarchy entered into ceasefire negotiations with the Italians. On November 2 in Padua, the latter demanded – besides the immediate cessation of hostilities – complete demobilisation, the withdrawal not only from the occupied areas but also from those regions south of the Brenner that had previously belonged to the Danube Monarchy, as well as complete freedom of movement within enemy territory.

The indignant generals of the collaborating Habsburg Empire viewed these conditions as the demand for a definitive and complete capitulation, but had to cave in to the Italians by instruction of Emperor Charles.

As a result the Austrians ceased immediately every form of combat, while the Italians had exercised a period of an additional 24 hours in order to inform their units of the ceasefire. The differing interpretation of the terms was solely at the cost of the Austro-Hungarian army command, meaning the taking prisoner of around 360,000 Austro-Hungarian soldiers, as it were at five to twelve.

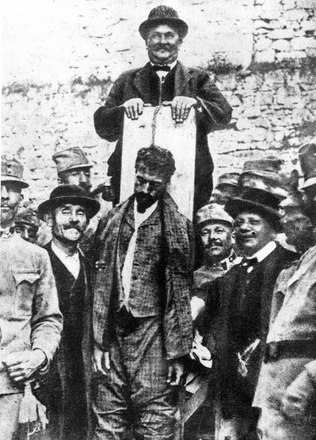

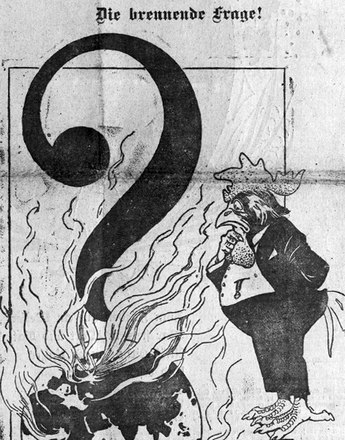

The rumours surrounding these events, above all the criticism levelled at the Apennine Kingdom of breaching its contract, deepened yet more the chasm between the previous enemies. The traditional distance felt towards the southern neighbour was now compounded in Austria by further animosity due to their experiences in the world war, while conversely the Danube Monarchy’s measures on the Apennine Peninsula directed against many ‘Austro-Italians’ became part of the national anti-Austrian myth. In particular, the fate of Cesare Battisti aroused emotions in this context: the former Austrian parliamentarian, who had decided to join the Italian army, was taken prisoner by the Austro-Hungarian troops and executed for high treason.

In contrast, the fact that from 1918/19 onwards the southern neighbour and former enemy sent considerable aid to the suffering, deprived Austrian population barely left an imprint on the historical consciousness of the emerging Alpine republic. Instead, indignation at Italy’s claim to South Tyrol was the dominant emotion in Vienna and the provinces.

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2013

Rauscher, Walter: Österreich und Italien 1918–1955, in: Koch, Klaus et al. (Hrsg.): Von Saint Germain zum Belvedere. Österreich und Europa 1919–1955, Wien 2007, 186-209