While Germany made use of the Austro-Hungarian naval bases on the Adria for the deployment of submarines, this part of the Mediterranean remained merely a sideshow for most countries.

In 1914 the bulk of the French fleet was located north of Navarino; their deployment, however, remained limited due to the danger of enemy submarines. Besides the latter, it was therefore mainly light and fast ships that were deployed.

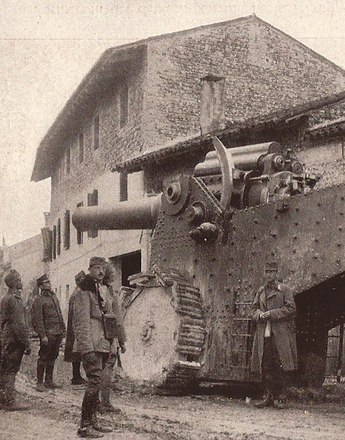

Italy, which was linked to the French and British marine forces on the basis of a Marine Convention of May 10, 1915, and which was given command of operations in the Adria, had to reconsider its strategy for this reason. While thought was initially given to a decisive battle, soon the focus was on coastal batteries, railway guns, airplanes and motor torpedo boats for the protection of sovereign territory. In contrast, the Austro-Hungarian units lay on the opposite shores of Dalmatia, protected by many islands and a rugged coastline. Yet smaller ships of the Italian navy recorded some successes.

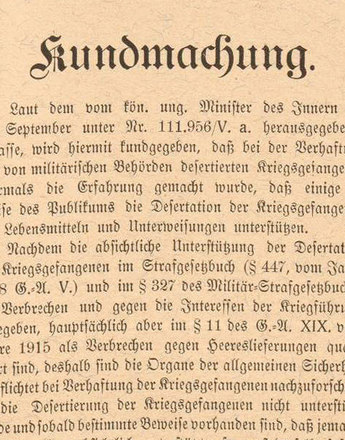

Blockade measures became especially important. In order to prevent Austrian and German operations, the Entente blocked the Straits of Otranto between Italy and Albania by means of nets, mines and the deployment of British and Italian destroyers.

Besides surprise actions launched on Italian coasts and the attempt to obstruct the evacuation of the Serbian army out of Durazzo by assaults, the main concern of the Austro-Hungarian fleet were the Straits of Otranto. Here they could then register a naval victory in May 1917 too, which loosened the blockade at least until July.

The original conditions were soon reestablished. The success of the Habsburg navy sank into oblivion, its recent attack on the Straits of Otranto failed from the outset. Allied forces were warned and on June 10, 1918 torpedoed the Austro-Hungarian battleship ‘SMS Szent István’.

These events marked the turning point in the war – both at sea and on land. The Central Powers could barely notch up any more successes. Their submarine warfare rather resulted in the USA entering the war on the side of the western powers.

Moreover, the events that took place in the naval fleet symbolised the general dissatisfaction. At the start of February 1918 the Austro-Hungarian sailors revolted in Cattaro, while late in the autumn of the same year their German colleagues made it clear that they were no longer willing to engage in any further military action. The mutiny in Kiel heralded the collapse of the system and the end of the Hohenzollern Monarchy.

Gröbig, Klaus: Unterseeboot S.M.U. 12. Die k. u. k. U-Bootflotte Österreich-Ungarns, Kiel 2009

Moritz, Verena/Leidinger, Hannes: Die Nacht des Kirpitschnikow. Eine andere Geschichte des Ersten Weltkriegs, Wien 2006

Noppen, Ryan: Austro-Hungarian battleships 1914–1918, Oxford 2012

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2013