After orders were refused among his military units, Italy’s Chief of Staff Luigi Cadorna realised that the soldiers needed a break. Yet his measures gave the impression after the eleventh Isonzo battle (mid-August to mid-September 1917) that he would soon go back on the offensive. Adequate defence positions were dispensed with. All guns remained on the foremost front line.

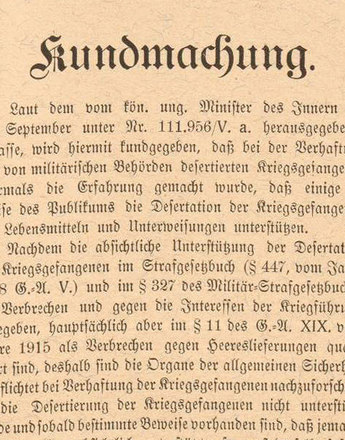

The next blow was delivered under these conditions by the Central Powers. Germany moved seven divisions to the upper Isonzo. Together with the Austrian-Hungarian units, they succeeded in breaking through on October 24, 1917, and advancing to the Piave by mid-November. The ‘catastrophe of Caporetto’, as the Italians described the 12th Isonzo battle, brought to light significant shortcomings on the part of the Apennine Kingdom. Besides 40,000 casualties and injuries, as well as 280,000 prisoners of war, the Italian armed forces lost tens of thousands of men through desertion. Mutinies pointed to the deep dissatisfaction felt in the country. Many deserters found refuge among peasants. Revolts and protests in Turin and Milan drew attention to the shortage of provisions and a swelling anti-war mood. The army cracked down harshly, with demonstrators killed and military personnel sentenced to disciplinary punishment and the death sentence.

The possibility of a breakthrough by Italy was real. Yet a revolution did not occur, whereby it was precisely the ‘disaster of Caporetto’ that played an important role, heightening national readiness to offer resistance: after the 12th Isonzo battle, the offensive war turned into a defensive one, which once again mobilised the available forces including allied reinforcements, distributed resources better and thus extended the powers of the state.

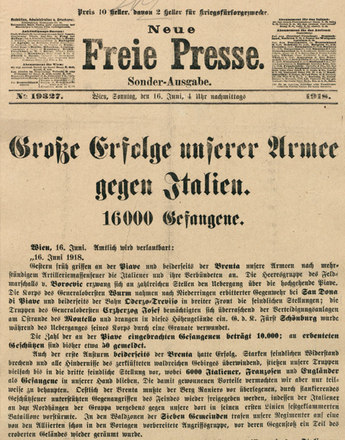

Conversely, in the Habsburg Empire in December 1917, when the fronts came to a standstill, the masses of prisoners taken were gawped at in fascination, yet they also now had to be fed. From the perspective of the overall Austro-Hungarian prosecution of the war, the victory on the Southwest Front rather brought with it dangers for the Monarchy. While soldiers and war materiel were transferred from one place to another, fuel and provisions were in short supply in the cities and larger towns.

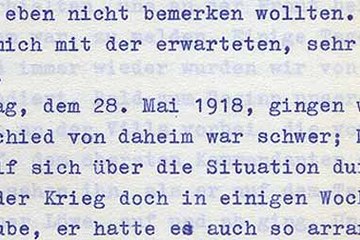

The problems back home were mixed up with the needs at the front. When the Austro-Hungarian army attacked on the Piave in June 1918, it was exposed to the pressure from the hinterland. The offensive failed. Exhausted, poorly equipped and half-starved soldiers also struggled with diseases such as malaria in the months to follow. At the end of August and beginning of September 1918 two-thirds of the Austro-Hungarian divisions were only at half-strength.

Isnenghi, Mario/Rochat, G.: La grande guerra 1914–1918, Mailand 2000

Rauchensteiner, Manfried (Hrsg.): Waffentreue: Die 12. Isonzoschlacht 1917, Wien 2007

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2013

Strachan, Hew: Der Erste Weltkrieg. Eine neue illustrierte Geschichte, München 2009