-

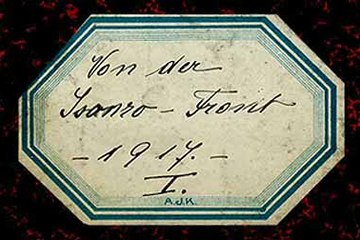

Story The Italian Front

Austria and Italy at the End of the First World War and in the Post-war Years

The seriously damaged relations between both countries improved to some extent only in view of later ambitions of an ideological and power-political nature. The fascist government of Benito Mussolini, which endeavoured to exert influence in the Danubian region and in so doing supported in particular authoritarian regimes, anti-socialist and anti-marxist movements, was regarded with ongoing suspicion in Austria, however. Resentment towards the ‘contract-breaching, unreliable and treacherous neighbours’ was even heightened in view of the threat to the ‘austro-fascist corporate state’ from the National Socialist German Empire.

In comparison with the decade following 1945, the military forces of foreign powers barely made a visible mark on public life in the Alpine Republic in 1918. The control exercised by the victorious allied powers came about to some extent by means of an indirect, anonymous restriction of state sovereignty, not through numerous military units. Relatively small troop contingents were billeted in the ‘hinterland’. Nonetheless, Italy was in this regard a certain exception. Apart from its forces in North Tyrol, it was the Apennine Kingdom’s claims on Viennese treasures that aroused emotions.

Although the South Tyrolean question was the cause of continual conflict, Vienna and Rome did achieve rapprochment in larger geo-strategic matters, too. In this, Italy’s striving to be a great power, revealed both in its imperialism in the Mediterannean region and in a stronger focus on Central Europe, proved especially important. For example, during the ‘Carinthian defence struggle’, a defensive alliance with Austria was directed against the opponents on the Adriatic, i.e. the South Slavic Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, known by the acronym ‘SHS-State’. Under Mussolini this willingness to cooperate took on markedly more aggressive and decidedly anti-marxist traits. The ‘Duce’ gambled on cooperation with conservative, authoritarian and fascist forces in Hungary and Austria. To this end, those countries’ heads of government, Gyula Gömbös and Engelbert Dollfuß, signed the so-called ‘Rome Protocols’ in 1934, a pact of friendship directed both against Berlin and Paris.

Only shortly afterwards, however, Italy’s waging a colonial war against Ethiopia, at the time called Abyssinia, led to international condemnation of the fascist regime. Mussolini alone found an ally in Hitler. In the shadow of the Rome-Berlin axis, Italy relinquished its function as a protective power of the sovereign ‘austro-fascist’ government. The path to annexation, to the ‘Anschluss’ of 1938 was laid, especially as the western powers saw no cause for intervention in view of the agreement reached at the same time between Vienna and Berlin in July 1936.

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Die Republik Österreich 1918/2008. Überblick, Zwischenbilanz, Neubewertung, Wien 2008

Rauscher, Walter: Österreich und Italien 1918–1955, in: Koch, Klaus et al. (Hrsg.): Von Saint Germain zum Belvedere. Österreich und Europa 1919–1955, Wien 2007, 186-209