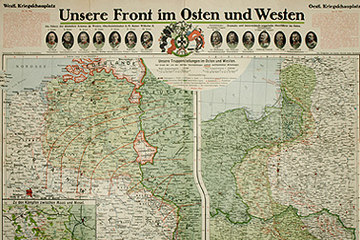

Even during the war the Eastern Front faded from the propaganda and media depiction spotlight compared to the theatre of war in the West. However, it is no longer true to describe discussion of the battles in the Bukovina, Galicia and the Russian part of Poland, the Baltic states and Volhynia as a neglected subject.

At times the ‘deployment and combat zone in the East’ was considered ‘regeneration space for wounded fighters from the Western front’. Additionally, the lack of canonised recollections led to various fragmented views and perceptions. On the other hand, the battles on the Western Front were seen as the crucial ones of the war. It was here, and not in the East, that the ‘modern technological war’ was located. On the battlefields of Belgium and France the ‘great showdown’ seemed to be equally dreadful and dense as it was mainly concentrated on trench and position warfare.

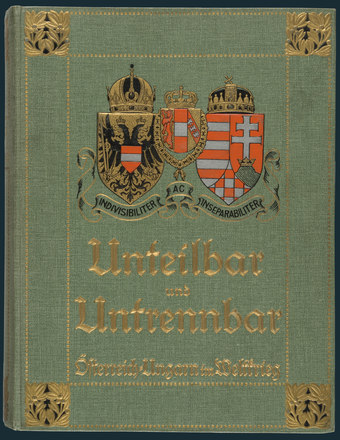

The visual memory that became increasingly important for the recollection of the war first reinforced this impression very effectively with the film classic ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’ from 1930, based on the eponymous novel by Erich Maria Remarque. On the contrary the encounters between the Tsarist Army and the military formations of the Central Powers had always, with a few exceptions, played a lesser role in the Austro-Hungarian (visual) propaganda right up to 1918: photo collections depict the first years of the war with great gaps and also with divergent emphasis on themes. State film productions were slow to organise and then featured mainly events in France and Italy. Two major obstacles stood in the way of visualising the Eastern front’: the organisational development and strategic focus of visual propaganda on the one hand, and the increasing lack of interest of the audience on the other, as can be seen from the marginalisation of the war in feature film productions.

In the long run the demise of the Habsburg Empire and the Romanov Dynasty led to a deliberate fading-out of the battles that took place on the territories between the Baltic States and the Black Sea. The leaders of Soviet Russia quite deliberately replaced any extensive examination of events between 1914 and 1917/18 with an idealisation and distortion of the Bolshevik coup d'état; in turn, the nostalgic view of the ‘good old days’ was culturally connoted in Austria, based on clichés and countenanced mainly as shallow entertainment with no political or military traces remaining. Both strands of myth, that of the Habsburgs and that of ‘Red October’, managed to survive without need of World War One.

However, in many quarters some rethinking can be detected. For some time now Russia has been contemplating the erection of monuments to commemorate soldiers who died in action in the final war of the Romanov Dynasty. Additionally, there is growing interest on the part of international scholarship. Not only was there a major conference in Berlin in 2004 with the ensuing publication of an anthology of theatres of war of the Austro-Hungarian, Hohenzollern and Tsarist armies; there have also been Anglo-Saxon publications with very detailed depictions of the military encounters between the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea.

Groß, Gerhard Paul (Hrsg.): Die vergessene Front – der Osten 1914-15. Ereignis, Wirkung, Nachwirkung, Paderborn/München/Wien 2006

Neiberg, Michael/Jordan, David (Hrsg.): The Eastern Front 1914-1920. From Tannenberg to the Russo-Polish War, London 2008

Rott, Irving G.: Battles East. A History of the Eastern Front of the First World War, Baltimore 2007

-

Chapters

- ‘The Forgotten Front’ – The Long Neglect and New Interest in the ‘East’

- Characteristics in Warfare at the Russian Front

- The Results of the Offensives and Territorial Gains

- War against the Local Population

- The Opening Military Campaigns

- The Calamity of the Tsarist Army

- Russia’s ‘Last Gasp’

- The Russian Revolution and the Fragile Peace in the ‘East’

- Occupation

- Never Ending Violence