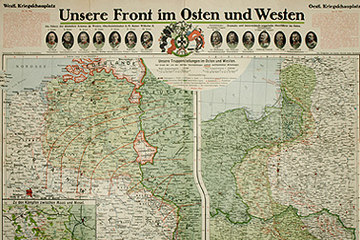

The war in the Eastern Europe was time and again characterised by considerable territorial gains. This, despite the fact that large-scale military operations were impeded not only by the geography, climate and vastness of the country, but also by the rudimentary motorisation, poor road network and problems with replenishment, supplies and communication.

The terrain between the Baltic States and the Black Sea is by and large only slightly hilly or even flat, but nonetheless, the Pripet Marshes to the south of Minsk and north of Volhynia, and the Carpathian Mountains on the Polish and Hungarian border would distinctly complicate military operations. An additional complication came in the form of poorly developed road and rail networks.

However, some factors facilitated the military attacks. The soil and weather conditions impaired trench warfare and there were fewer troops deployed in this vast combat area than in the West. Especially the Romanov and the Habsburg Empires were unable to fully exhaust the potential of their manpower fit for military service for organisational and financial reasons. In the summer of 1914 the Tsarist Army with five million soldiers was no larger than the Hohenzollern army despite the fact that Russia’s population was much greater. And the Austro-Hungarian army only ever managed half the number of army divisions compared to those of the Germans.

Thus the troops of the Hohenzollern constituted a considerable power factor in a strip of land that expanded over 1,600 kilometres after Romania joined the war in August 1916, that formed no continuous front unlike in the West, and that contained far fewer soldiers than on the battlefields of Belgium and France. This already became apparent in the winter of 1915/16: the Romanov Empire managed 1,200 soldiers per kilometre of front whilst Russia's allied forces on the Western Front employed 2,100 solders for a similar length of land. According to further calculations there were also two thirds more rifles than to be found on battlegrounds of the Tsarist army.

Under these circumstances ‘mobile warfare’ prevailed ‘in the East’ which can be divided into various phases: the Russian offensive in East Prussia and Galicia; more or less unsuccessful undertakings from October 1914 until March 1915; the retreat of the Tsarist Army from Russian Poland and Galicia starting in May 1915; failed Russian forays into East Galicia and Belorussia at the turn of 1915/16; the successful so-called ‘Brusilov Offensive’ against the Austro-Hungarian military formations as well as Romania’s entry into the war and its defeat in 1916; the ‘Kerensky Offensive’ and Russian Revolution respectively; the considerable territorial gains of the Central Powers before and with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk; civil wars and battles between the intervening powers respectively, nationalist movements and new states in the wake of the collapse of the old monarchs of Central and Eastern Europe up to the end of the Polish-Soviet War in 1921.

Dowling, Timothy C.: The Brusilov Offensive, Bloomington 2008

Neiberg, Michael/Jordan, David (Hrsg.): The Eastern Front 1914–1920. From Tannenberg to the Russo-Polish War, London 2008

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2013

Rott, Irving G.: Battles East. A History of the Eastern Front of the First World War, Baltimore 2007

-

Chapters

- ‘The Forgotten Front’ – The Long Neglect and New Interest in the ‘East’

- Characteristics in Warfare at the Russian Front

- The Results of the Offensives and Territorial Gains

- War against the Local Population

- The Opening Military Campaigns

- The Calamity of the Tsarist Army

- Russia’s ‘Last Gasp’

- The Russian Revolution and the Fragile Peace in the ‘East’

- Occupation

- Never Ending Violence