The armies of the belligerent powers often viewed the population that still lived near the frontlines as an unwanted nuisance. The increasing nervousness and intensified ‘Russophile’ image of the enemy in the wake of the commencment of hostilities thus took its toll on the civilian population on the Eastern Front, too. There were several orders that decreed ‘ruthless actions’ towards ‘suspects and possible traitors’. Whoever was not ‘massacred and without mercy’ on the spot faced a policy of rigorous deportation.

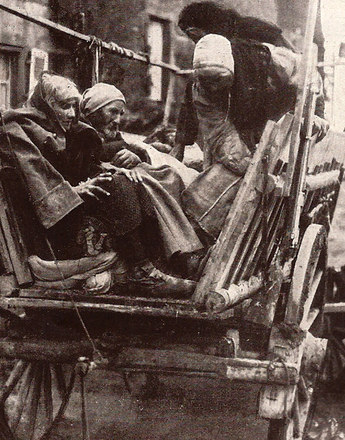

In many parts of Galicia the local populace was treated in a most inhumane manner: entire villages were burnt to the ground for ‘strategic reasons’, residents often dispelled at ‘bayonet point’ without explanation and without even letting them take along any of their personal belongings. Also the transport conditions to the new destinations were disastrous, men and women, women and little children were ruthlessly separated by the military commanders. Many people died of hypothermia in the open and unheated cattle wagons due to lack of proper clothing; at the same time similar scenes of misery took place in the front and base territories of the Tsarist Army. Here too, the military officers expelled parts of the local population without mercy or appropriate precautionary measures. Many people died of malnutrition, pneumonia, cholera or typhus.

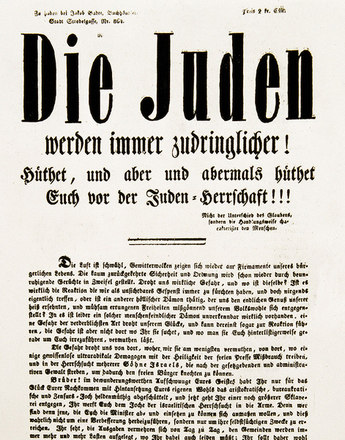

These scenes of misery partially showed the ‘modernising shortfalls’ in the regions concerned, but even more so the state apparatus being overwhelmed by the ‘masses’ of refugees, detainees and prisoners of war that ‘had to be administered to’. But there were other reasons as well: even before 1914, widespread hysteria concerning espionage and treason now escalated into a conduct of war that was racist and radical; the patriotism now on show with its attendant rejection of anyone or anything different meant that civilians were now increasingly targeted.

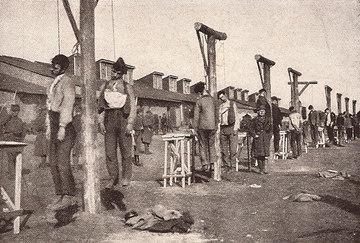

As a result of this the Austro-Hungarian battle forces made ‘extensive use’ of the ‘right for self-defence’ against ‘Russophiles’ right from the start, which meant that they shot anyone suspicious on the spot, took hostages who were executed at will, accused entire villages of treason and as a consequence ‘flattened them to the ground’. Others were taken to the detention camps of Gmünd, Theresienstadt and Thalerhof near Graz where they were subject to new torments after having suffered appalling conditions on their transports. They were jammed together in tents and barracks with no more than starvation rations, and so in Thalerhof alone at least 2,000 of the 30,000 Ruthenians – men, women and children – from Galicia and Bukovina died of malnutrition, exhaustion and typhus between 1914 and 1917.

The Russian army behaved no better, especially towards the Jewish population who often saw themselves confronted with the most unfounded of accusations. They were vilified as ‘troublemakers’, ‘spies’ and ‘saboteurs’ and as a consequence, like many Ruthenians, fell victim to numerous different assaults. There is documentation from different regions of violent excesses against the local population, many women falling victim to rape, in many places synagogues and entire living quarters burnt to the ground, thousands accused of treason and hundreds sentenced to death or executed without trial.

Gatrell, Peter: A Whole Empire Walking. Refugees in Russia during World War I, Bloomington/Indianapolis 1999

Leidinger, Hannes: „Der Einzug des Galgens und des Mordes“. Die parlamentarischen Stellungnahmen polnischer und ruthenischer Reichsratsabgeordneter zu den Massenhinrichtungen in Galizien 1914/15, in: Zeitgeschichte, 33. Jg. Sept./Okt. 2006, H. 5, 235-260

Mentzel, Walter: Kriegsflüchtlinge in Cisleithanien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Diss. Wien 1997

Wendland, Anna Veronika: Die Russophilen in Galizien, Wien 2001

Zielinski, Konrad: The Shtetl in Poland, 1914–1918, in: Katz, Steven T. (Hrsg.): The Shtetl. New Evaluations, New York/London 2007, 102-120

-

Chapters

- ‘The Forgotten Front’ – The Long Neglect and New Interest in the ‘East’

- Characteristics in Warfare at the Russian Front

- The Results of the Offensives and Territorial Gains

- War against the Local Population

- The Opening Military Campaigns

- The Calamity of the Tsarist Army

- Russia’s ‘Last Gasp’

- The Russian Revolution and the Fragile Peace in the ‘East’

- Occupation

- Never Ending Violence