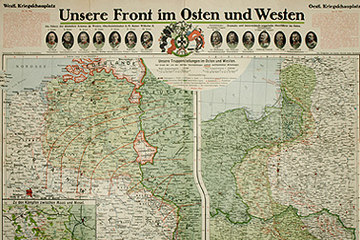

In the whole of Europe the military commanders preferred an offensive strategy, but after only a few months it became apparent that their attacks had failed nearly everywhere. Thus in the West trench and static warfare began. In the East the opening military campaigns turned out to be quite different right from the start.

The widely questioned military clout of the Habsburg army proved insufficient indeed when faced with the challenge of the Tsarist Army in the north-east of the Danube Monarchy. The Austro-Hungarian Field Army Command (FAC) under Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf still believed they had to take the initiative. Austro-Hungarian troops were to intercept the Polish rail lines and to attack the enemy which was advancing towards East Prussia from behind.

Instead of prestige-bringing success, Conrad had humbly to report the loss of territories in Galicia. Admittedly the initial defeat could be ascribed to the greater ‘human potential’ of the Romanov Empire and the quick concentration of the Tsarist troops, but the FAC had also misjudged the ways and means of moving the so-called B-Squadron in time from the Balkans to the ‘Russian front’. The raw defeats of the Austro-Hungarians with the fall of Lemberg and Przemyśl castle leading the way went hand-in-hand with an appalling loss of human lives, especially on the part of the Austro-Hungarian army. More than half of the 800,000 soldiers who were employed in the north-eastern theatre of war were either killed, wounded or taken prisoners of war.

In comparison the Russians, superior in numbers, had ‘only’ lost 250,000 men; all the same they could not really enjoy their triumph. Their 1st and 2nd army under Pavel Rennenkampf and Alexander Samsonov were defeated near Tannenberg by the German defenders under Paul von Hindenburg and his chief of staff Erich Ludendorff. After his troops had been trapped and worn down, Samsonov took his own life. 92,000 soldiers of the Romanov army were taken prisoners of war according to official information of the Hohenzollern Empire, with another 50,000 either wounded or killed. As a result of the German victory Rennenkampf's troops turned back. They returned to the Tsarist territories on September 13, 1914.

Despite the fact that the Eastern Front was more permeable, ambitious advances into enemy territories often failed. Yet there did not seem to be a change of thinking on the part of the military commanders. Despite their past experiences the leading military staff still hoped for the storming and conquest of enemy positions. Given that precisely at the ‘Russian Front’ they could report some territorial gains, they still subsequently kept up the offensive, notwithstanding some disillusionment setting in.

Groß, Gerhard P. (Hrsg.): Die vergessene Front. Der Osten 1914/15. Ereignis, Wirkung, Nachwirkung, Paderborn/München/Wien 2006

Herwig, Holger H.: The First World War. Germany and Austria-Hungary 1914–1918, London/New York/Sydney 1997

Stevenson, David: 1914–1918. The History of the First World War, London/New York 2004

Strachan, Hew: Der Erste Weltkrieg. Eine neue illustrierte Geschichte, 3. Auflage, München 2009

-

Chapters

- ‘The Forgotten Front’ – The Long Neglect and New Interest in the ‘East’

- Characteristics in Warfare at the Russian Front

- The Results of the Offensives and Territorial Gains

- War against the Local Population

- The Opening Military Campaigns

- The Calamity of the Tsarist Army

- Russia’s ‘Last Gasp’

- The Russian Revolution and the Fragile Peace in the ‘East’

- Occupation

- Never Ending Violence