Unlike the interim government that had been in office since the ‘February Revolution’, the Bolsheviks under Vladimir I. Lenin advocated an end to the ‘Imperial War’, and so managed not least of all to speak to battle-weary soldiers and large parts of the population. After the ‘October Revolution’ the new Soviet government under Lenin immediately sought to conclude a ceasefire.

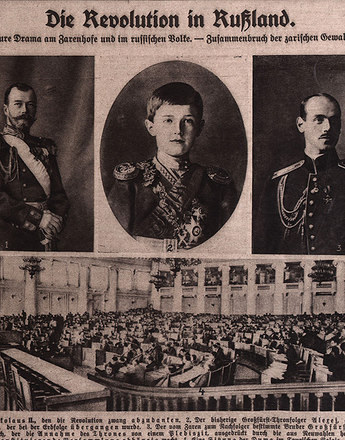

Since the February Revolution Russia had experienced a rapid decline in state structures and hierarchies. However, the Bolsheviks, who initially profited from this, had to create new instruments of domination after their rise to power at the end of 1917. Among other actions they formed the Red Army which proved essential for the maintenance of the Soviet Republic.

At the same time the ‘October Regime’ appealed to world public opinion with pro-peace slogans. Much to the dismay of the allies, who had hoped to keep Russia in the war on their side, the Bolsheviks – who officially called themselves Communists from the spring of 1918 onwards and who very rapidly established a single-party dictatorship in their power base – decided on a ceasefire and ensuing negotiations with the Central Powers.

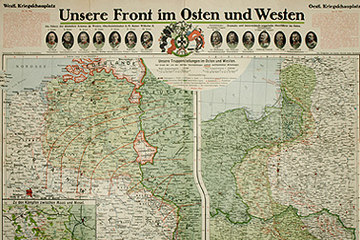

But the German Empire in particular – which in the course of the war had allowed its Austro-Hungarian ally only the status of vassal – made it quite clear to Lenin’s Soviet government and the Council of People's Commissars that it was Germany that was to set the terms for the treaty.

The talks, which stalled as a result of that and initially failed, ended with an ultimatum and a renewed advance on the part of the Germans and Austrians. Simultaneously, separatist movements and national states arose in the border regions of the extinct Tsarist Empire to the west, which stood up to the Soviet leadership that from henceforth resided in Moscow.

Against this backdrop Lenin and his most important comrade-in-arms Lev Trotsky were again temporarily interested in an alliance with the Entente. Finally, however, they accepted the harsh peace conditions that also entailed considerable loss of territories, signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on March 3, 1918.

For Lenin the agreements reached with Emperor Wilhelm’s generals were merely tactical manoeuvres serving as a reprieve before the world revolution that the Bolsheviks hoped for and expected, whilst even amongst the sympathisers of the ‘Governing Councils’ they were received rather controversially. Thus the Brest-Litovsk Treaty remained rather fragile. In the ‘Territories of the East’ controlled by the Central Powers there were repeated uprisings by partially pro-Soviet forces. Along the German-Russian demarcation line there was no lack of encroachments and border violations.

Meanwhile, the Kremlin government waited in vain for the ‘revolution in the West’. Social and economic crises as well as the collapse of the Hohenzollern and Habsburg Empires were only marginally influenced by the ‘Russian example’. Sympathy for Lenin's beliefs remained limited to individual issues and protest movements.

Figes, Orlando: Die Tragödie eines Volkes. Die Epoche der russischen Revolution 1891–1924, Berlin 1998

Moritz, Verena/Leidinger, Hannes: Die Russische Revolution, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2011

-

Chapters

- ‘The Forgotten Front’ – The Long Neglect and New Interest in the ‘East’

- Characteristics in Warfare at the Russian Front

- The Results of the Offensives and Territorial Gains

- War against the Local Population

- The Opening Military Campaigns

- The Calamity of the Tsarist Army

- Russia’s ‘Last Gasp’

- The Russian Revolution and the Fragile Peace in the ‘East’

- Occupation

- Never Ending Violence