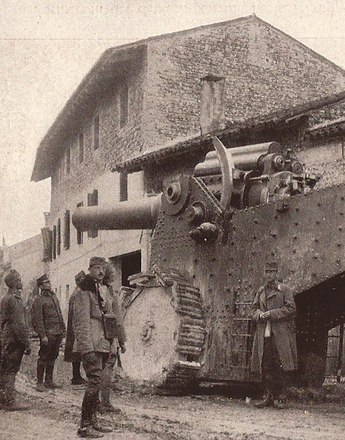

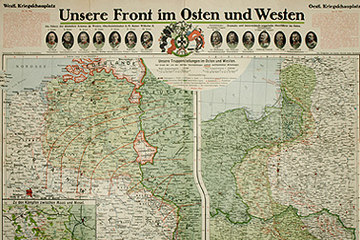

Added to ‘effective killing’ there were the demographic consequences in the East, the consequences of industrial ‘machine warfare’ with hitherto unknown effects of mass mobilisation. This was reflected in long lists of troops both deceased and wounded, and prisoners of war. The mobile warfare also affected the civilians of these simply vast theatres of war, the various bases and the occupied areas.

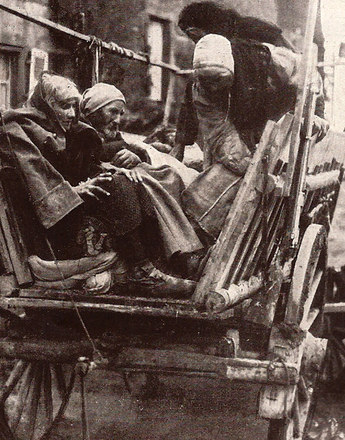

Besides prisoners of war, the front areas between the Baltic States and the Black Sea as well as in the hinterlands of the Hohenzollern, Habsburg and Tsarist Empires were marked by forced migration. In Russian Poland alone 750,000 people were forced to resettle by the Tsarist Army. Similar deportations were organised by the Russian forces in 1914 during their opening offensive in East Prussia, though ‘only’ 13,600 people were affected by this. However, most people were not forcibly deported, or taken to particular locations or detained, but left their home territory ‘of their own devices’ because of the fighting. Around 500,000 people were affected in Prussia, who were, however, mostly able to return to their homes soon after with the advancing Central Powers.

The same happened to hundreds of thousands of people who had left the battle zones of Galicia, though they were forced to find shelter in the hinterlands due to the continuous threat on the north-western border of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. The Russian ‘Brusilov Offensive’ in particular unleashed another exodus which caused the Imperial authorities to wait for a while with repatriation. The results of this decision were seen later after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy when there were still 310,000 ‘non-German’ refugees on the territory of what became the Republic of Austria.

In particular the Empire of Tsar Nicholas II was affected by permanent uprooting of large segments of the population due to the advance of the Hohenzollern army into Poland and the Baltic States. The responsible authorities in St. Petersburg talked about three million ‘people without a homeland’ at the end of 1915, and just before the February Revolution even about five to six million people, thus some five percent of the entire population.

Subsequently the German and Austro-Hungarian troops must have felt confirmed in their belief that the conquered territories were but deserted wasteland. In the end the population density was vastly depleted by the fighting. For example, Lithuania lost a quarter of its pre-war population, the Kurland even lost more than half.

Gatrell, Peter: A Whole Empire Walking. Refugees in Russia during World War I, Bloomington/Indianapolis 1999

Mentzel, Walter: Kriegsflüchtlinge in Cisleithanien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Diss. Wien 1997

-

Chapters

- ‘The Forgotten Front’ – The Long Neglect and New Interest in the ‘East’

- Characteristics in Warfare at the Russian Front

- The Results of the Offensives and Territorial Gains

- War against the Local Population

- The Opening Military Campaigns

- The Calamity of the Tsarist Army

- Russia’s ‘Last Gasp’

- The Russian Revolution and the Fragile Peace in the ‘East’

- Occupation

- Never Ending Violence