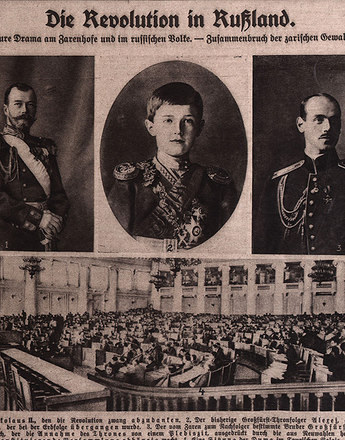

Despite their defeats in 1915 the Tsarist Army still managed to deal considerable blows to the Central Powers. General Aleksei Brusilov destroyed entire Austro-Hungarian armies in June 1916, although the offensive was by no means an operation that decisively turned the course of war. The temporary government that followed the downfall of the Tsar in spring 1917 tried once more to succeed on the battlefields, yet just caused yet more destabilisation within Russia.

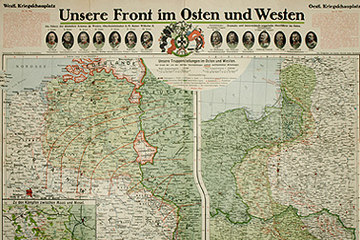

The Austro-Hungarian high commanders had withdrawn troops from the Eastern Front to the offensives in Verdun and the Tyrol. General Aleksei A. Brusilov, who was the High Commander on the Russian Southwest Front, had also been forced by the Entente Powers to launch offensives that would relieve pressure, and tried to make use of his relatively advantageous starting point. With 600,000 troops facing only 500,000 enemy soldiers he defeated or rather crushed the 4th and 7th Austro-Hungarian Army. His tactic was not to focus on concentrated attacks, but on a series of planned, rapid, ambush-style advances along a wide front. As a result the forces of the Austro-Hungarian Army were almost halved. The Tsarist Army took approximately 200,000 prisoners of war, but their frontal attacks that reached the Carpathian Mountains in the South towards Hungary petered out.

When the enemy closed their gaps in the defence lines and fought off the following attacks, the tide seemed to turn again in favour of the Russians. Moreover, the Bucharest government declared war on the Habsburg Monarchy. This move was caused not least by territorial promises made by the Entente. Already Bulgaria's entry into the war in the autumn of 1915 caused Bucharest's neutrality increasingly to waver. Romania was mainly interested in the capture of Transylvania and subsequently summoned a mixed alliance of the Central Powers, which operated from out of Bulgaria, and saw itself simultaneously challenged by Austro-Hungarian operations in the North. The attack by the Tsarist Army ended after only a few months with the retreat of the Romanian Army to Moldova, and with the invasion of Bucharest by the Central Powers at the end of 1916.

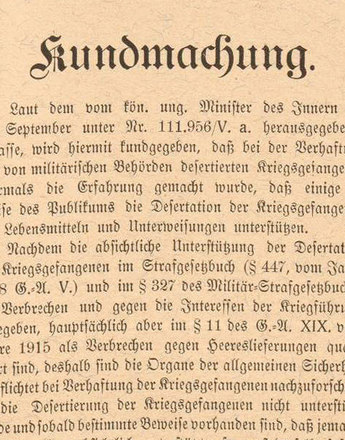

After a period of calm on the eastern and south-eastern theatres of war, Alexander Kerensky, who had been Minister of War since May and Prime Minister of the interim government since July, once again took the initiative following the February Revolution. But the offensive named after him did not anywhere achieve the hoped-for breakthrough. Also, the Russian forces’ initial will to fight proved a flash in the pan. On the contrary, the signs of a complete breakup of the army became more frequent. It was not only the Finnish, Polish and Ukrainian units who refused to obey orders, but also Russian soldiers who deserted in large numbers. At the same time the Central Powers switched from defensive to offensive tactics. On September 3, 1917 German troops invaded Riga. The Russian capital St. Petersburg, then called Petrograd, appeared under threat from a possible advance by Hohenzollern troops as well.

Dowling, Timothy C.: The Brusilov Offensive, Bloomington 2008

Neiberg, Michael/Jordan, David (Hrsg.): The Eastern Front 1914–1920. From Tannenberg to the Russo-Polish War, London 2008

Rott, Irving G.: Battles East. A History of the Eastern Front of the First World War, Baltimore 2007

-

Chapters

- ‘The Forgotten Front’ – The Long Neglect and New Interest in the ‘East’

- Characteristics in Warfare at the Russian Front

- The Results of the Offensives and Territorial Gains

- War against the Local Population

- The Opening Military Campaigns

- The Calamity of the Tsarist Army

- Russia’s ‘Last Gasp’

- The Russian Revolution and the Fragile Peace in the ‘East’

- Occupation

- Never Ending Violence