‘We’ll hold out’: The Functions and Applications of Children’s and Teenage Literature in the First World War

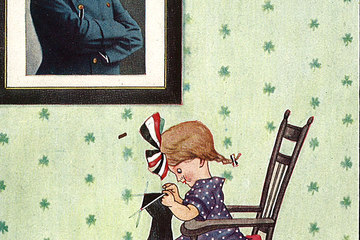

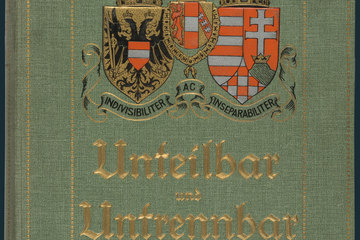

As far back as 1774, Empress Maria Theresa had declared in her decree on school reform that ‘the education of youth of both sexes (...) [was] the most important fundament for the true happiness of nations.’ One of the approved teaching methods was the targeted educational use of children’s and teenage literature. Austria and Germany were particularly productive in this field, with Nuremberg and Vienna being the most important centres of publishing. It was inevitable, then, that war propaganda would extend its reach to literature for young people.