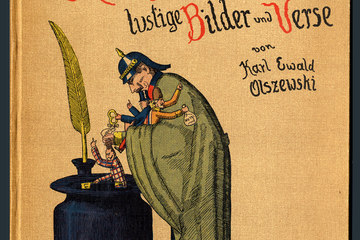

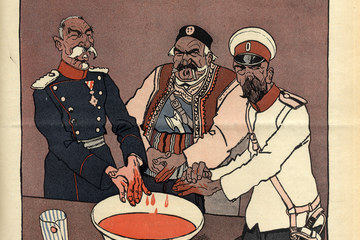

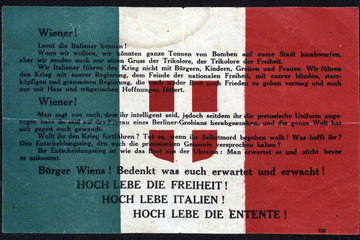

Children as the target of war propaganda

All the belligerent states made children and teenagers the target of intensive propaganda with the aim of integrating them into the conflict. Parents, schools and clubs as well as books, songs and games were the main vehicles of this mobilization. The aim of this ideologization was to convey the concept of a ‘just war’, to evoke enthusiasm in the children and to recruit them for activities that supported the war effort.