No Role to Play and yet part of Austria’s Heritage: the Habsburgs after 1918

-

Nossa senhora do Monte, photo from Wiener Bilder of 31 March 1935

Copyright: ÖNB/ANNO

Partner: Austrian National Library -

Bruno Kreisky and Otto Habsburg-Lothringen shaking hands on the occasion of a ceremony to mark 50 years of the Pan-European Movement, 1972

Copyright: ÖNB Bildarchiv

Partner: Austrian National Library

When the Republic was proclaimed the imperial house of Habsburg and all family members had all their privileges withdrawn, members of the bureaucracy and the military were released from their oath of loyalty to the emperor, and the imperial ministries were wound up. However, before he left Austria in March 1919, Emperor Karl still emphasized in a manifesto that for him the measures passed by the new government were ‘null and void’. The newly elected National Assembly reacted to this provocation by expelling the imperial family from the country and confiscating their property. At the same time a law was passed which forbade the use of aristocratic titles and made it a punishable offence.

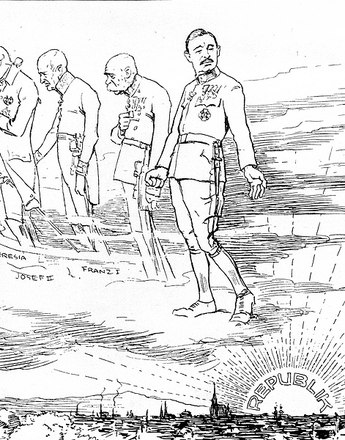

Attitudes towards the Habsburgs in the First Republic were basically determined by the political polarization between the Social Democrats and the Christian Socialists, in social terms between the working class and the bourgeoisie. The left wing dissociated itself politically from the Monarchy and the Habsburg dynasty in a clear and consistent way, with the unsuccessful attempt by ex-emperor Karl to regain the throne in Hungary in 1921 serving to strengthen this position. When Karl, coming from Hungary, travelled through Austria in a special train on his way to Switzerland for the second time, a deputation of Social Democrats was waiting for him in Feldkirch, the last station before the border. They had a special farewell message for him; from a hill above the station the local railwaymen’s band played two well-known folk songs, Muss i denn zum Städtele hinaus (Must I now leave this town) and O Du lieber Augustin, alles ist hin (Oh, dear Augustine, everything’s gone). In addition there was waiting at the station a gallows with a life-size doll in old Austrian military uniform. Among the Austrian bourgeoisie there was an increasingly positive interpretation of the monarchy. As early as 1923, troops in the military parades to mark the founding of the republic wore decorations from the days of the empire, while the playing of the Radetzky March caused further controversy. In the years of the corporate state between 1934 and 1938 the Catholic right-wing again intensified their ‘Habsburg revival’.

These contrary attitudes towards the Habsburgs can also be seen in the Second Republic up to the beginning of the 1970s. The conservative ÖVP may not have involved the members of monarchist groups directly in party affairs, but representatives of the conservative-catholic wing, like the long-serving Minister of Education, Heinrich Drimmel, and others, repeatedly referred to the great achievements of the multinational Habsburg Monarchy in their public speeches and publications, stressing its importance for the Austrian national identity and thus clearly distinguishing this from Pan-Germanism.

The early 1960s saw the so-called ‘Habsburg crisis’, which almost caused the collapse of the coalition government of the SPÖ and the ÖVP. The son of the last emperor, Otto Habsburg, aroused the displeasure of the Social Democrats when he criticized Karl Renner for his positive attitude towards the Anschluss, the union with Germany in 1938, and then also for his letter ‘to His Excellency Marshall Stalin’ in 1945, in which Renner tried to present himself as the guarantor of an independent Austria. In 1961 Otto was finally prepared to sign a declaration of his definitive renunciation of the throne, which the SPÖ, which was not exactly kindly disposed towards him, did not regard as sufficient. There were some emotional debates in Parliament and among the public. In October 1966, when Otto Habsburg entered Austria for the first time, members of the SPÖ and their sympathizers reacted by holding large-scale protests.

Together with the generally negative assessment of the First Republic the Social Democrats also reached a more positive view of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. In this ‘reconciliation’ Bruno Kreisky played a key role. In 1972 the differences between the Habsburgs and the SPÖ came to an end with a highly symbolic handshake between Bruno Kreisky and Otto Habsburg.

In his final years in government Kreisky exploited the positive attitude towards the monarchy and its representatives by surrounding himself with Habsburg symbols. He was known as the ‘Sun King’ and, for example, had himself photographed in front of a portrait of the young Franz Joseph for a brochure used in the election campaign of 1979; he also liked to give television interviews sitting beneath a portrait of Joseph II. Kreisky is reported to have responded to protests about the brochure with the words, ‘Well, what am I supposed to do? After all, the emperor is fixed to the wall back there, isn’t he?’

By the 1980s the topic of the Habsburgs had by and large become a politically neutral one. When Zita, the widow of Emperor Karl, was buried in Vienna in 1989, the ceremony was stage-managed as a grandiose and folkloric act of memory. In the Habsburgs’ former imperial residences, the Hofburg and Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, what was cultivated was above all a way of remembering the Habsburgs that was appropriate for museums. The focus was on large-scale exhibitions that would attract large crowds and on the touristic and commercial marketing of the monarchy, especially the two iconic figures of Franz Joseph and his consort Elisabeth, as well as the ‘Styrian’ archduke Johann. It is only within the last few years that in these places a more differentiated view of the monarchy and the imperial family has been provided, one that is committed to the historical facts.

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Cole, Laurence: Der Habsburger-Mythos, in: Brix, Emil u.a. (Hrsg.): Memoria Austriae I. Menschen, Mythen, Zeiten, Wien 2004, 473-504

Reisacher, Martin: Die Konstruktion des „Staats, den keiner wollte“. Der Transformationsprozess des umstrittenen Gedächtnisorts „Erste Republik“ in einen negativen rhetorischen Topos. Diplomarbeit Wien 2010. Unter: http://othes.univie.ac.at/10190/1/2010-06-07_0252520.pdf (20.06.2014)

Quotes:

„Well, what am I supposed to do? ...": zitiert nach: Scheidl, Hans-Werner: Wahlkampf mit Bruno (1), in: Die Presse vom 30.08.2013. Unter: http://diepresse.com/home/meinung/pizzicato/1446725/Wahlkampf-mit-Bruno-1 (20.06.2014) (Translation)

-

Chapters

- 12 November 1918 as a Site of Memory

- The New State in Search of its National Holiday: 12 November as the Site of Political Dividing Lines

- Austria, the Country without a National Anthem

- Disputed Zones: Monuments and Street Names

- Myths and Narratives: ‘The Rest is Austria!’ … or something like that

- Myths and Narratives: ‘The Reluctant State’ and ‘The State that Nobody Wanted’

- No Role to Play and yet part of Austria’s Heritage: the Habsburgs after 1918