Myths and Narratives: ‘The Rest is Austria!’ … or something like that

„L’Autriche c’est qu’il reste“, „L’Autriche se que reste“, „L’Autriche, c’est qui reste“, „L’Autriche c’est que reste“, „L’Autriche est ce qui reste“

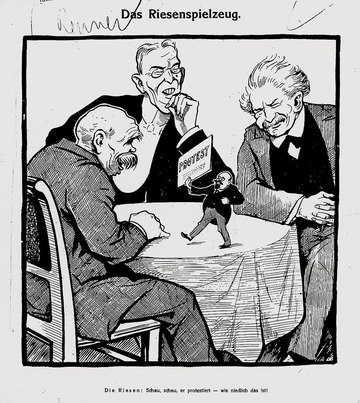

These different forms of the famous saying by the French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau can be found in various publications on the treaty of Saint Germain-en-Laye, in which Austria’s frontiers were laid down. All these versions have one thing in common: they are not correct linguistically – and hence could hardly have been uttered by a French foreign minister with a command of French. How is it possible, the historian Manfred Zollinger asks, that there is such a variety of false citations, and that in connection with a key utterance which even today still exerts a great influence on the discourse relating to the treaty negotiations and the status of Austria? It seems likely that what is involved here is a translation back from a German sentence. By making him simply turn Austria into a small state, Clemenceau was to be represented as the one who caused the subsequent catastrophe. And who did so, as various commentaries, including those by contemporary historians, put it in flowery way, in a manner that was ‘sneering’, cynical’, ‘derisive’, ‘disdainful’ or ‘contemptuous’.

To date it has not been possible to find any evidence that Clemenceau actually made such a remark – in any form whatsoever, either in sources from the time before the peace negotiations or in later reminiscences published in newspapers. A first ‘preliminary form’ of the supposed quote can be found in a text written in 1930 by Hermann Neubacher, later promoted by the Nazis to the position of mayor of Vienna: ‘[T]he rest is Austria’ – without, however, any reference to it having possibly been uttered by Clemenceau. Seven years later Neubacher’s phrase reappears in the writings of the historian Viktor Bibl: ‘ “The rest is Austria!” – this is the cynical phrase of Clemenceau’s which tore to shreds the document on national self-determination for German-Austria.’ Finally in 1938 the quote and the author can be found in the Handbuch für den Deutschunterricht (Handbook for the Teaching of German) in the formulation which became usual after 1945: ‘ “Le reste c’est l’Autriche,” as Clemenceau put it, “The rest is Austria.” ’

That this supposed abusive remark served as the ideological basis for claiming the legitimacy of union with Germany is obvious. It is consistent with a series of (self-coined) descriptions of the First Republic, which made Austria ‘merely a blood-stained rag, a construction at the mercy of the favour or disfavour of the victors’, a ‘cripple’, a ‘torso’, a ‘freak’ or the ‘appendix of Europe’. Some of these phrases were again used in the political discourse of the Second Republic in different contexts as a conscious or unconscious appeal against the ‘dismemberment’ of Austria: ‘The rest is Austria’ became a permanent but never really challenged component of both scholarly and popular history books dealing with the beginnings of the First Republic.

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Zollinger, Manfred: „L’Autriche, c’est moi“? Georges Clemenceau, das neue Österreich und das Werden eines Mythos, in: Karner, Stefan (Hrsg.): Österreich – 90 Jahre Republik. Beitragsband der Ausstellung im Parlament. Innsbruck/Wien u.a. 2008, 621-632

Quotes:

all quotes from: Zollinger, Manfred: „L’Autriche, c’est moi“? Georges Clemenceau, das neue Österreich und das Werden eines Mythos, in: Karner, Stefan (Hrsg.): Österreich – 90 Jahre Republik. Beitragsband der Ausstellung im Parlament. Innsbruck/Wien u.a. 2008, 621-632 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- 12 November 1918 as a Site of Memory

- The New State in Search of its National Holiday: 12 November as the Site of Political Dividing Lines

- Austria, the Country without a National Anthem

- Disputed Zones: Monuments and Street Names

- Myths and Narratives: ‘The Rest is Austria!’ … or something like that

- Myths and Narratives: ‘The Reluctant State’ and ‘The State that Nobody Wanted’

- No Role to Play and yet part of Austria’s Heritage: the Habsburgs after 1918