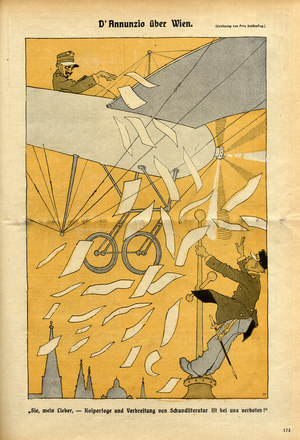

It was not until the second half of the war that airborne leafleting was recognized as an effective instrument of psychological warfare. Mostly printed on one side only, these publications were dropped over the front in hazardous actions in an attempt to demoralize enemy troops.

During the war leaflets were dropped in their hundreds of thousands to disseminate political messages, primarily among enemy soldiery but also among the population on the home front. Combining punchy slogans and topicality with clear, immediately comprehensible messages made them a proven instrument of propaganda. Britain and France made extensive use of leafleting; in Great Britain alone, more than twenty-one million leaflets were printed and distributed. They were scattered over enemy lines from aeroplanes, balloons, airships and even distributed by canon.

The aim of the leaflets was to disseminate information as widely and effectively as possible, to report on the current state of affairs and to spread rumours. Leaflet propaganda relied on ‘truth’ as the strongest weapon in the battle for hearts and minds. In fact it employed distortion, omission and exaggeration, conveying selective information in its efforts to influence opinion.

Leaflets were also used to demoralize the enemy civilian population as well as enemy troops. It exhorted the latter to go over to the enemy, promising they would receive decent treatment and rations as prisoners of war. A typical example is provided by the following British leaflet, purporting to be written by a captured German soldier: “[…] Don’t believe those gentlemen who tell you that you will be badly treated in captivity; quite the contrary. We can assure you that we get more to eat in one day than with those bloodsuckers over there in three. […]”

This is followed by a direct incitement to desert: “And now a piece of advice! It is so easy to lose one’s way while on patrol or fetching mess rations; now it’s easier than ever. We’ve had our eyes opened in the short time we’ve been here.”

The leaflets were psychologically well thought out and cunningly fostered the infiltration of the enemy. Particularly effective were facsimile letters and postcards that were frequently indistinguishable from the original and because of their perceived authenticity went unrecognized as propaganda. These bogus missives also gave favourable accounts of experiences in captivity and encouraged their readers to desert.

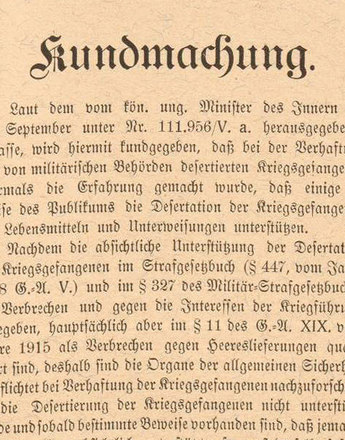

Stock leaflets were not contingent upon the actual war situation and were therefore printed and distributed in great numbers. Often disguised as newspapers, they contained detailed articles and conveyed the impression of impartial reporting. They were also intended to foster fear and doubt among enemy troops.

Priority leaflets were particularly effective because of their topicality. They often showed maps with the latest front lines and contained the most recent information. These were also intended to undermine enemy morale, foster mistrust and drive a wedge between the rank-and-file and their officers.

As a medium of propaganda, leaflets were successful in spreading doubt among soldiers as to which information they could trust. In this way they opened up or enlarged the fault-line between loyalty and mistrust among the enemy forces.

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Brunner, Frederike Maria: Die deutschsprachige Flugblatt- und Plakatpropaganda der österreichisch-ungarischen Monarchie im Ersten Weltkrieg 1914-1918, unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Wien 1971

Gering, Matthias, Kriegsflugblätter als Propagandamedium, in: Zühlke, Raoul, Bildpropaganda im Ersten Weltkrieg, Hamburg 2000, 213-238

Kirchner, Klaus: Flugblattpropaganda im 1. Weltkrieg. Bd. I. Flugblätter aus England 1914-1918, Erlangen 1985

Quotes:

„[…] Glaubt den Herren nicht,...“: englisches Kriegsflugblatt, „Aus der Kriegsgefangenschaft“, Codezeichen A.P.66., Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

„Und dann, einen guten Rat!...“: englisches Kriegsflugblatt, „Aus der Kriegsgefangenschaft“, Codezeichen A.P.66., Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

-

Chapters

- Propaganda: psychological warfare in the First World War

- The battle for hearts and minds.

- Friend and foe – guilt and innocence in First World War propaganda

- “Let your hearts beat for God and your fists beat the enemy”

- The First World War as reflected in the distortions of caricature

- The war on the wall

- Truth from the clouds

- The Emperor’s Voice

- Tones and Sounds