The poster had been used as a medium of communication for commercial purposes well before the First World War, and advertising art had already become established as a separate branch of art production. With the advent of war the poster became a modern vehicle of political content.

As a propaganda medium, posters were used principally on the home front. As wall newspapers they proclaimed official orders, regulated supplies of foodstuffs, mobilized the patriotic emotions of the nation and served to recruit volunteers. They could also be used to draw the public’s attention to collection drives and donation campaigns, and to relay politically slanted messages.

Posters produced during the war years primarily communicated messages connected to the wartime economy. Drawing on the tradition of consumer promotion, they now propagated austerity and sacrifice. A poster published by the borough authorities in Vienna in August 1914 exhorted citizens to plant winter vegetables in order to prevent food shortages: “Every patch of earth, every working man and woman must produce food. It is the duty of every thinking citizen to participate! Wrest from the soil what it is capable of yielding!”

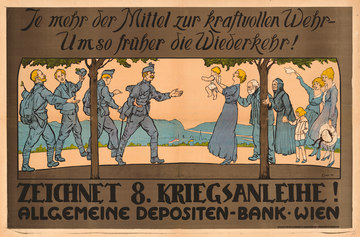

Numerous posters appealed to the individual’s sense of duty to contribute to victory. War bonds were advertised as a way of reinforcing personal commitment to the cause. Posters were also used by the banks offering the bonds as well as state institutions and private initiatives to organize collections.

In poster propaganda, patriotic rhetoric could be translated into monumental images. The pictorial subjects appealed to the population to show unity; the multi-national empire was to face up to the external enemy as a united body. The solidarity of the Crown Lands and the sworn harmony between the nations that made up the empire were expressed in a demonstrative loyalty to the emperor.

In their choice of subject the war posters produced in Austria-Hungary took German war propaganda as their model. References to the other ethnic groups of the Habsburg Monarchy were marginal and appeared, if at all, on the posters produced by local associations and initiatives.

The posters tended to address the onlooker directly: figures and pairs of eyes that seemed to stand out from the pictorial surface and fix passers-by in their gaze were typical of the ‘psychological strategies’ and aims of these posters. However, their effect was contingent upon other propaganda media. The press campaigns created the horizon of understanding on which these pictorial metaphors were based. The subjects depicted in the posters defined the slogans more precisely, condensing content into a motif that was immediately comprehensible. Once a successful pictorial subject had been created it was passed on to other propaganda media, appearing as a patriotic postcard, on stamps or objects of everyday use such as matchboxes or tram tickets.

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Denscher, Bernhard, Gold gab ich für Eisen. Österreichische Kriegsplakate 1914-1918, Wien/München 1987

Eybl, Erik: Information. Propaganda. Kunst. Österreichisch-ungarische und französische Plakate des Ersten Weltkriegs, Wien 2010

Jaworsky, Rudolf: Deutsche und tschechiche Ansichten. Kollektive Identifikationsangebote auf Bildpostkarten in der späten Habrsburgermonarchie, Innsbruck/Wien/Bozen 2006, 127-131

Kämpfer, Frank: Plakat, poster, affiche, manifesto … Des Weltkriegs große bunte Bilder, in: Zühlke, Raoul (Hrsg.) Bildpropaganda im Ersten Weltkrieg, Hamburg 2000, 125-144

Verhey, Jeffrey: „Helft uns siegen“ – Die Bildsprache des Plakats im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Spilker, Rolf/Ulrich, Bernd: Der Tod als Maschinist. Der industrialisierte Krieg 1914-1918. Eine Ausstellung des Museums Industriekultur Osnabrück im Rahmen des Jubiläums „350 Jahre Westfälischer Friede“ 17.Mai – 23.August 1998, 164-175

-

Chapters

- Propaganda: psychological warfare in the First World War

- The battle for hearts and minds.

- Friend and foe – guilt and innocence in First World War propaganda

- “Let your hearts beat for God and your fists beat the enemy”

- The First World War as reflected in the distortions of caricature

- The war on the wall

- Truth from the clouds

- The Emperor’s Voice

- Tones and Sounds