Withdrawal and the development of more independent perspectives

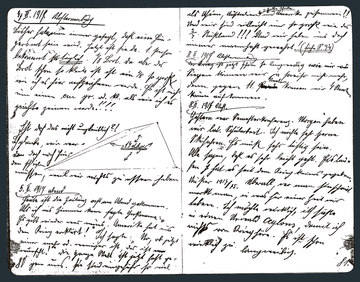

“Something new to report: America has declared war on us!”, extract from the diary of schoolboy Richard Ruffingshofer

Copyright: Dokumentation lebensgeschichtlicher Aufzeichnungen, Institut für Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte der Universität Wien

Partner: Dokumentation lebensgeschichtlicher Aufzeichnungen, Institut für Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte der Universität Wien

-

“Real Austrians are those who fight for their Fatherland,” extract from the diary of schoolgirl Anna Hörmann

Copyright: Dokumentation lebensgeschichtlicher Aufzeichnungen, Institut für Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte der Universität Wien

Partner: Dokumentation lebensgeschichtlicher Aufzeichnungen, Institut für Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte der Universität Wien

Although numerous measures were aimed at the uniform mobilization of children, they experienced the war in very different ways. As the war progressed they increasingly turned their backs on propaganda and developed their own views of events.

A close examination of autobiographical sources written by children reveals quite clearly that they underwent very different experiences during the war. For example, their experience of shortages – a subject that is treated in detail in many childhood memoirs – varied, depending on their age, the socio-economic status of their family and regional background. In rural areas hunger and privation made themselves felt to a lesser degree and at a later stage of the war than in urban centres. Equally, the cultural by-products of war that were aimed at children (games, books and magazines) had a stronger resonance in the middle-classes than in the urban underclass or in rural areas.

It is in fact striking that the war occupies a relatively minor role in some of the autobiographical sources on childhood, and that memories of the conflict overlap with those of the post-war period – evidently many of the experiences that children had during the war, such as shortages and privation, were very similar to those of the following years.

Children who came from nations that were now enemy states – so-called Feindkinde (enemy children) – experienced discrimination and victimization on a daily basis. Altercations and physical attacks, not only between children but also between adults and children and their families, were common, even in the years following the peace negotiations. For example, German children living in Belgium were forbidden to attend state schools until 1924, with the same law applying to Belgian children domiciled in Germany.

Teenagers who had joined up as volunteers returned disillusioned from the front, their hopes of being celebrated as war heroes ending in many cases in mental distress and physical disability.

As the years went by, children and teenagers lost interest in the war. Propaganda in games, books and magazines became less intense, and the war was spoken about less in the classroom. From 1917 onwards it became a marginal subject at school, and even after the end of the war there was no resurgence of patriotism in the classroom.

It should also be emphasized that some children resisted these propaganda messages. It is telling that children took an active part in protests during the starvation winter of 1916/17. Hunger and privation led to demonstrations and food riots, in which children and teenagers participated in increasingly large numbers. A police report from January 1917 records that a procession of 150 to 300 women and children demonstrated in front of the municipal district offices in Hernals, a poor district of Vienna, before moving on to the Ministry of War, to protest against the catastrophic supply situation.

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Hämmerle, Christa (Hrsg.): Kindheit im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien/Köln/Weimar 1993

Healy, Maureen:Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. Total War and Everyday Life in World War I, Cambridge 2004, 211-257