Children as the target of war propaganda

-

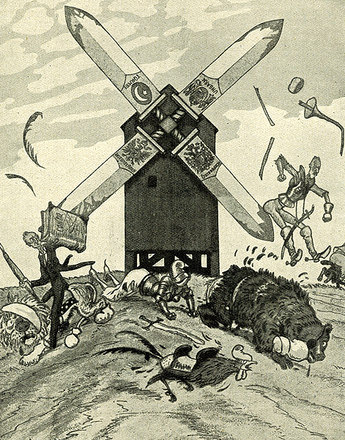

Hanns Anker: War enthusiasm, drawing, 1917

Copyright: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur-und Betriebsges.m.b.H./Fotograf: Alexander E. Koller

Partner: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H. -

“If the Fatherland calls me to fight, I will go forward with all my might”, propaganda postcard

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

All the belligerent states made children and teenagers the target of intensive propaganda with the aim of integrating them into the conflict. Parents, schools and clubs as well as books, songs and games were the main vehicles of this mobilization. The aim of this ideologization was to convey the concept of a ‘just war’, to evoke enthusiasm in the children and to recruit them for activities that supported the war effort.

During the First World War the countries involved also sought to win the support of women and children for the war. In addition to the forces fighting in the various theatres of war, the hinterland or home front was also expected to contribute to achieving the war aims. Children were by no means exempt from this mobilization and duly became the target of war propaganda.

The reasons for this intensive ‘infiltration’ of the younger generation were many and varied. On the one hand the authorities were keen to actively win over children and young people in direct support of the war effort and to use them as a workforce. On the other hand children were used to disseminate propaganda. The authorities speculated with the huge influence children wielded over their parents, as revealed in a memorandum from the Ministry of Culture and Education: “School children will be instructed on the importance of the initiative and encouraged to secure the support of their parents. Young people will devote themselves to this task with enthusiasm and zeal, and not without success, considering how receptive parents are towards their children’s requests.”

Children were co-opted to convey norms, values and politically biased information to parents and families.

There was also another reason for this intensive mobilization. In Austria-Hungary, Great Britain, Germany and France the war was viewed ideologically as a conflict between civilizations. As the generation of the future, children played a crucial role. Parents, teachers and ideologists seem to have been convinced that the war would have an educational effect on children. The young generation was expected to emerge from the conflict as an elite, more industrious, earnest and patriotic than the cohort that had preceded it.

Duty, discipline and obedience played a central role in the messages transported by teachers, parents and other figures of authority. Pupils were intended to demonstrate these qualities by working for various patriotic initiatives. Active support for these initiatives was encouraged by the portrayal of the conflict as a war waged in defence of Austria-Hungary and Germany. This argument was bolstered by the perceived betrayal by Italy of its commitment to the Triple Alliance. Other circumstances that were exploited for propaganda purposes included the general privation and shortages, which were represented as being caused by enemy states rather than by mistakes in national economic planning. Fears were deliberately stoked by invoking the horrifying prospect of the ‘food and goods blockade’.

Children were expected to make their own contribution to the ‘success of the war’. Victory or defeat was portrayed as depending just as much on the ‘war effort behind the lines’ as on military defence of the homeland. Whether it was by displaying patriotism and particularly good behaviour, by praying for the soldiers or in doing actual war work, children had a duty to support their brothers and fathers at the front: “Surely you can’t find it so very difficult! Think of the great sacrifices your fathers and brothers are making, the unimaginable travails and privations they have accepted, even risking their lives for their Fatherland.”

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Audoin-Rouzeau, Stephane: Die mobilisierten Kinder: Erziehung zum Krieg an französischen Schulen, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard /Krumeich, Gerd /Renz, Irina (Hrsg.), „Keiner fühlt sich hier mehr als Mensch…“. Erlebnis und Wirkung des Ersten Weltkriegs, Essen 1993, 151-174

Demm, Eberhard: Deutschlands Kinder im Ersten Weltkrieg. Zwischen Propaganda und Sozialfürsorge, in: Militärgeschichtliche Zeitschrift (2001), 60, 51-79

Hämmerle, Christa (Hrsg.): Kindheit im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien/Köln/Weimar 1993

Quotes:

„Das kann euch doch nicht schwer fallen!...“: Verordnungsblatt für das Volksschulwesen in der Grafschaft Mähren, redigiert im k.k. Landesschulrat, ausgegeben am 15. Jänner 1917, Nr. 1, quoted from: Hämmerle, Christa (Hrsg.): Kindheit im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien/Köln/Weimar 1993, 295

„Die Schuljugend werde über die Bedeutung…“: Verordnungsblatt für das Volksschulwesen in der Grafschaft Mähren, redigiert im k.k. Landesschulrat, ausgegeben am 15. Jänner 1917, Nr. 1, quoted from: Hämmerle, Christa (Hrsg.): Kindheit im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien/Köln/Weimar 1993, 307