The First World War – child’s play

-

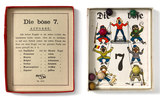

“The evil 7”, child’s game, around 1914

Copyright: Wien Museum

-

“All around the wide world”, board game, early 20th century

Copyright: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur-und Betriebsges.m.b.H./Fotograf: Alexander E. Koller

-

“On the Danube Canal: an enemy being captured”, propaganda postcard from the series “Our children in a great age”

Copyright: Wien Museum

Partner: Wien Museum

As the war increasingly made its presence felt in children’s everyday life, it also began to appear in the games they played. The general militarization of society also took hold in the nation’s nurseries. Role-play strengthened emotional ties with the aims of the war, while board and card games conveyed propaganda messages.

The games and toy industry reacted quickly to the initial enthusiasm for the war. Building on the established tradition of war toys and games of strategy, most of the new additions and new versions appearing on the market between 1914 and 1916 had the war as their theme. Miniature lead soldiers, trenches and artillery pieces, prisoner transports and field hospitals started to appear in nurseries. New versions of existing games were brought out, their design and narrative featuring clear references to the war. This was especially evident in the adaptation of parlour games which now included the re-enactment of battles.

The martial tendency of these games fulfilled a clear educational function: the graphics, terminology and design of the toy figures were intended to convey a new world order and version of history, the events of the war were aestheticized, soldiers shown as heroic models and virtue, duty and obedience held up as central values. Rhyming phrases and slogans reinforced emotional internalization of patriotism and loyalty to the Fatherland, while battle and siege games made combat appear harmless. Card games such as Weltkriegsquartett conveyed technical and military knowledge, and illustrations reinforced enemy stereotypes.

Through play children adopted friend-and-foe constellations, became inculcated with racist stereotypes and built up mental images of the enemy. In their games hostile states were disparaged as figures of ridicule, while the armies of their own nation and their allies were glorified.

With the outbreak of hostilities the war dominated children’s role play, which became pervaded with military vocabulary. Popular in all social strata and often organized by the state in patriotic associations or Jugendwehren (a sort of territorial organization for boys), were out-of-door war games. With the aim of re-enacting the war as realistically as possible, children armed themselves with iron bars, catapults and knives, dug trenches and stormed ‘enemy troops’ with might and main. Often these war games were played with such intensity that they degenerated into mass brawls, but in any event educational indoctrination was here reinforced by physical enactment.

Through the combination of narrative, form and rules of the game suggestive messages could be conveyed which were absorbed intensively through play and the urge to win that was inherent in these games. In playing them, children developed an enthusiasm for soldierly life, practised military terminology and internalized ideological concepts.

As the war continued, interest in war toys diminished, and war games began to disappear from the shelves. They were replaced with more abstract games that were not primarily focused on the war and dispensed with military images and warlike subjects. As the war everywhere encroached on all aspects of life, playful enjoyment of it dwindled away.

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Demm, Eberhard: Deutschlands Kinder im Ersten Weltkrieg. Zwischen Propaganda und Sozialfürsorge, in: Militärgeschichtliche Zeitschrift (2001), 60, 51-79

Hoffmann, Heike: „Schwarzer Peter im Weltkrieg“. Die deutsche Spielwarenindustrie 1914-1918, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard et al. (Hrsg.): Kriegserfahrungen. Studien zur Sozial- und Mentalitätsgeschichte des Ersten Weltkriegs, Essen 1997, 323-335

Strouha, Ernst: Spiel und Propaganda. Antisemitismus, Krieg und Ideologien in Gesellschaftsspielen 1900 -1945, in: Ausstellungskatalog Spiele der Stadt. Glück, Gewinn und Zeitvertreib, Wien/New York 2013, 136-145