The End of Monarchy, the Birth of New States

‘Earth from Bohemia, earth from Hungary, earth from Slovenia … earth from Austria’: With these words in his drama The Third of November 1918 the author Franz Theodor Csokor buries not only a colonel of the Imperial and Royal Army who has committed suicide out of despair but also, in symbolic form, the Monarchy.

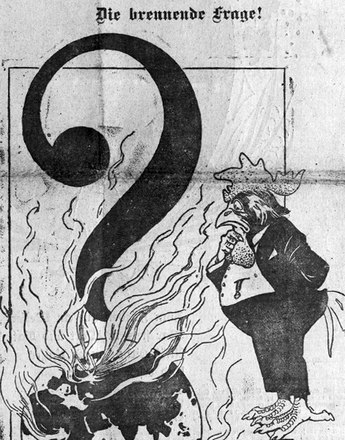

It was on 3 November 1918 that Austria-Hungary capitulated after it had become apparent that the military collapse of the Empire and the internal manifestations of disintegration could no longer be halted. Emperor Karl’s attempt to save the situation by means of a ‘peace note’ on 14 September came too late. It was rejected by the Allies. Karl’s ‘Peoples’ Manifesto’ of 16 October, which aimed to turn the Monarchy into a federal state, did not achieve the desired effect and contributed rather to its dissolution than to its consolidation. As early as 28 June 1918, that is to say exactly four years after the assassination of Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, Woodrow Wilson, the President of the United States, had declared that he wanted to support the liberation of all Slav peoples from German and Austro-Hungarian rule. On 6 October the national assembly of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes had met for the first time in Zagreb; on 28 October (still the national holiday of the present-day Czech Republic) the plenary assembly of the National Committee in Prague voted for the independence of the state of Czechoslovakia. On the same day the Polish deputies to the Austrian Reichsrat proclaimed the union of their formerly Habsburg Lands with the Polish state. And the German-speaking deputies from Cisleithania, that is to say the Austrian half of the Dual Monarchy, assembled on 21 October for the constituent session of the National Assembly of German-Austria, which was to include all the German-speaking areas of the Monarchy and to have access to the sea. The aim was to enter into a federation with the new national states that were being formed. However, such a union of states made up of the peoples of the Danube regions of the former monarchy found no support in the national assemblies in Prague, Ljubljana and Zagreb. Thus there were now two governments on Austrian territory, that of German-Austria, still existing only on paper, and that appointed by Emperor Karl on 27 October, led by Heinrich Lammasch but de facto without an empire. After the war had officially ended, the troops had been demobilized and the German emperor had abdicated, Emperor Karl was persuaded to renounce involvement in the business of government by Lammasch and Edmund von Gayer, the Interior Minister. On 11 November Karl’s signature on the previously formulated declaration of renunciation put an end to 640 years of Habsburg rule. The historian Ernst Hainsich has described this declaration as a ‘masterpiece of diplomatic equivocation’, since it includes some ambiguous formulations in connection with the word ‘renunciation’ – the use of the word ‘abdication’ was avoided, and this could thus later be exploited politically by those loyal to the emperor and the imperial family. The people’s emperor, as Karl saw himself, disappeared from Schönbrunn Palace through a side door.

And on the same day someone else left the political stage: the founder and chairman of the Social Democratic Party, Viktor Adler, who to the last had been involved in negotiations and held the office of Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in the provisional government, died of a heart condition.

The mass slaughter, which had started with such enthusiasm – even if this did not last throughout the war, came to an end not least as a result of mass strikes, desertions and protest movements. The sober balance sheet of figures shows that the war had cost the lives of between nine and ten million people, 1.5 million of them from the Austro-Hungarian armed forces, the equivalent of almost the total population of Vienna today. There were in addition some nine million prisoners of war, around 2.7 million of them from the Habsburg army, as well as countless wounded. It is impossible to calculate the economic consequences for all those who lost the basis of their existence and equally impossible to assess the psychological effects which the events of the war had on those affected. This was the burden which the Republic of German-Austria had to bear when it was finally proclaimed on 12 November 1918.

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Csokor, Franz Theodor: 3. November 1918, Wien/Hamburg 1936

Hanisch, Ernst: Der lange Schatten des Staates. Österreichische Gesellschaftsgeschichte im 20. Jahrhundert (= Österreichische Geschichte 1890–1990, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram), Wien 2005

Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumeich, Gerd/Renz, Irina: Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, Paderborn 2009

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Der Erste Weltkrieg. Wien/Köln/Weimar 2011

Rauchensteiner, Manfred: Österreich-Ungarn, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumreich, Gerd/Renz, Irina (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, aktualis. u. erw. Studienausg. Paderborn u.a. 2009, 64-86

Weinzierl, Erika/Skalnik, Kurt: Österreich 1918–1938. Geschichte der Ersten Republik, Graz/Wien/Köln 1983

Quotes:

„Earth from Bohemia, earth from Hungary ...": Csokor, Franz Theodor: 3. November 1918, Wien/Hamburg 1936 (Translation)

Sources about number of casualities of war:

Bihl, Wolfdieter: Der Weg zum Zusammenbruch. Österreich-Ungarn unter Karl I. (IV.), in: Weinzierl, Erika/Skalnik, Kurt: Österreich 1918–1938. Geschichte der Ersten Republik, Graz/Wien/Köln 1983, 27-51, hier 50f.

Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumeich, Gerd/Renz, Irina: Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, Paderborn 2009, hier 664f.

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Der Erste Weltkrieg. Wien/Köln/Weimar 2011, hier 46f.

-

Chapters

- The End of Monarchy, the Birth of New States

- 12 November 1918

- The Path to 12 November: ‘If there is no peace then there will be a revolution here’

- ‘We intended the strike to be a great revolutionary demonstration.’ The Social Democrats and the January Strike

- Was There an Austrian Revolution or Not?

- A Marxist on Ballhausplatz – Otto Bauer Takes Over Foreign Policy

- The End of the Dream: the Failure of Bauer’s Foreign Policy