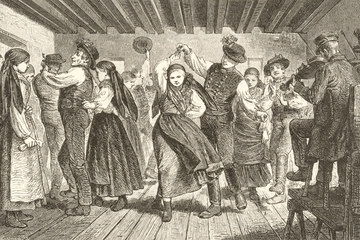

The situation of prisoners of war in Austria-Hungary

As early as late summer 1914, surprise was registered concerning the rapid rise in the numbers of prisoners of war in the 10th Department of the Austro-Hungarian War Ministry, which dealt with matters relating to soldiers captured in combat. After all, there were around 200,000 enemy soldiers in the hands of the Danube Monarchy, confronting the military authorities with new challenges.