Aid for prisoners for war

A range of differing organisations set themselves the goal of removing the numerous deficiencies in the prisoners of war system. Ultimately, however, all initiatives failed in the face of the sheer scale of the problems involved.

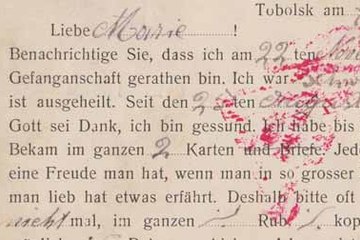

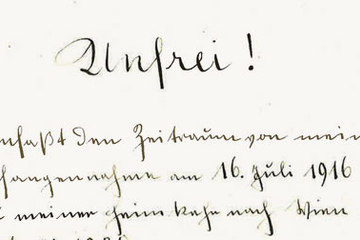

Charitable activities in favour of the ‘soldier behind barbed wire’ were also made more difficult due to the behaviour of those waging war. In all the states, repressive measures against the camp inmates occurred, regulations of international law were flouted, attempts to improve the situation failed due to the demand for ‘reciprocity’, i.e. mutuality. An early exchange of soldiers, and in particular of the disabled, could also be achieved only to a modest degree.

Neutral protective powers representing the interests of citizens of hostile countries were also initially confronted with various obstacles. However, the neutral countries did not apparently always show the appropriate interest in this task. Spanish diplomats in Germany and Austria-Hungary who were meant to take care of soldiers of the Tsarist army hardly found any fault with the conditions at the internment camps. Similarly reserved were the actions of the United States on the other hand, which had been entrusted with the fate of soldiers of the Habsburg and Hohenzollern armies in the Romanov Empire.

Greatly more effective than the ponderous mediation of embassies and consulates proved to be the actions of the various Red Cross organisations. Its International Committee had at its disposal a central information office with an impressive card index of individuals, and sent representatives to the warring countries. Furthermore, contacts among Europe’s aristocracy were exploited, their members mostly exerting considerable influence over the individual national aid organisations concerned.

Against this background, the visits of Russian and German, and also Austro-Hungarian, welfare nurses occurred, too. To be sure, they showed extraordinary devotion and personal courage from time to time, yet in the long term brought about no basic improvement in conditions with their so-called Visitiering (visitation) of the camps. Those who worked most efficiently, in contrast, were the Swedish delegates, who distributed more than one thousand wagon loads of ‘love gifts’ – mostly packages with food and clothing – from the Hohenzollern Empire and the Danube Monarchy to Central Powers’ soldiers located in the Russian Empire.

The Scandinavians operated as neutral protective powers in Russia, too, from 1917 onwards. Denmark and Sweden were certainly candidates of choice for the governments in Vienna and Berlin, whose administration now had to deal, moreover, with the effects of the collapse of the Romanov dynasty and the growing dissatisfaction with their own populations.

Incidentally, so-called ‘relatives’ associations’ featured increasingly among the key private initiatives, which were concerned with the fate of their family members in captivity, and which demanded increased involvement on the part of the central authorities concerned as well as the institutions they cooperated with, specifically ‘the keeping of records and dissemination of information with regard to military persons fallen into enemy hands’. However, the resources available for this on the part of official bodies were ever diminishing. The called-for improvement in aid to prisoners of war was ultimately hindered by the economic, social and political crisis that culminated in the collapse of the Danube Monarchy.

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Gefangenschaft, Revolution, Heimkehr. Die Bedeutung der Kriegsgefangenenproblematik für die Geschichte des Kommunismus in Mittel- und Osteuropa 1917–1920, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2003

Oltmer, Jochen (Hrsg.): Kriegsgefangene im Europa des Ersten Weltkriegs, Paderborn/München/Wien 2006

-

Chapters

- Numbers and Dimensions

- Captivity

- The situation of prisoners of war in Austria-Hungary

- Humanitarian catastrophes in captivity

- Aid for prisoners for war

- National propaganda and prisoners of war

- The relationship between prisoners of war and the civilian population

- The Meaning of Prisoners’ Labour

- Witnesses and actors in the revolution

- ‘Transport Home from Captivity’

- Difficult Homecoming