The consequences of the First World War often blocked the path to a rapid integration of home-comers from war captivity. Besides widespread economic and social problems, conflicts also arose in various countries motivated by ideology.

Straight after the end of the four-year mass slaughter, returnees from the battlefields and the former enemy states often belonged to the margins of society. Together with invalids and the unemployed they formed a potential for protest, especially in the Danube region, which played a key role in the political unrest in Austria and in the establishment of the council-based republic in Hungary.

Former prisoners of war rarely joined radical-left or communist parties for longer periods, however. Only individuals decided to leave their old homeland for good, in order to try a new start in the Soviet Union. The fact that most home-comers experienced long-term problems in integrating into their work and family life is evidenced, moreover, by the corresponding aid measures provided by various associations for former prisoners of war.

These were at pains to lend meaning to the experiences ‘in enemy hands’. The work done in remembering, which expressed itself in numerous association magazines, memoirs and exhibitions, increasingly sank into authoritarian waters in Germany and Austria, however. Against this background, men sought to interpret the ‘suffering behind barbed wire’ as a starting point for heightened patriotism. Patriotic feeling and ‘national solidarity’, it was said accordingly, had been ‘matured’ under catastrophic circumstances ‘far away’.

Yet these approaches to the Zeitgeist of the 1930s were insufficient to relocate the theme of captivity in war at the centre of public interest. It is striking how this problematic issue was kept silent in totalitarian regimes above all. The National Socialist, for example, practised mental preparation for war, and so harboured little sympathy for a depiction of captivity that, for all the stylisation of the camp as a microcosm of patriotic solidarity, still made crystal clear the dreadful consequences of a trial of strength by arms.

Italian fascism also recognised too much that was distracting in the fates of prisoners of war. Under Mussolini the theme was made a taboo as much as in the USSR. Time and again the image of cowardly and treacherous soldiers arose, who had gone over to the opponent’s side. Moreover, the Soviet authorities suspected that former prisoners under ‘foreign control’ had been ‘infected’ with ‘bourgeois’, anti-Bolshevist thinking. From this perspective it is no surprise that in the Soviet-Russian code of criminal law of 1926, being held captive was made the equivalent of high treason, carrying the death penalty. Eventually, in the ‘cleansing’ under Stalin, former prisoners of war were categorised as suspicious. They thus were among the first groups of victims of the ‘Great Terror’ from 1936 onwards.

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Gefangenschaft, Revolution, Heimkehr. Die Bedeutung der Kriegsgefangenenproblematik für die Geschichte des Kommunismus in Mittel- und Osteuropa 1917–1920, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2003

Moritz, Verena/Leidinger, Hannes: Zwischen Nutzen und Bedrohung. Die russischen Kriegsgefangenen in Österreich (1914–1921), Bonn 2005

Oltmer, Jochen (Hrsg.): Kriegsgefangene im Europa des Ersten Weltkriegs, Paderborn/München/Wien 2006

-

Chapters

- Numbers and Dimensions

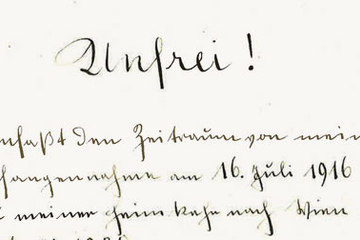

- Captivity

- The situation of prisoners of war in Austria-Hungary

- Humanitarian catastrophes in captivity

- Aid for prisoners for war

- National propaganda and prisoners of war

- The relationship between prisoners of war and the civilian population

- The Meaning of Prisoners’ Labour

- Witnesses and actors in the revolution

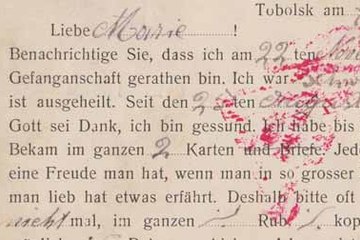

- ‘Transport Home from Captivity’

- Difficult Homecoming