The relationship between prisoners of war and the civilian population

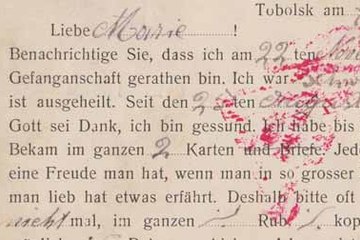

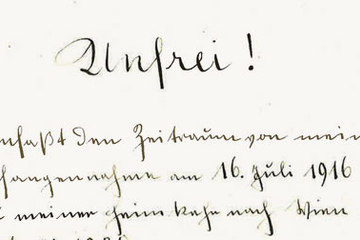

The military authorities were at pains to keep the enemy soldiers under their control as far away as possible from the local civilian population. As time passed, they had to acknowledge, however, that real fraternisation arose. Foreigners and locals were equally affected by the growing economic, social and political crisis.

In the course of time German military authorities increasingly bemoaned the lax guarding of prisoners of war. Their colleagues in the Danube Monarchy made similar complaints. For example, towards the end of 1915 they got worked up about the disregard for the ‘boundaries required by morality and decency’ between the local population and the ‘foreign military personnel’. In the relevant reports an everyday reality emerged in which prisoners not infrequently went to the cinema or pub after working hours ‘like normal workers’, or took part in other public events and amusements.

Both army circles and civilian authorities reacted particularly vehemently to the ‘intolerable behaviour’ of women and girls, who had ‘forgotten themselves... in their contact’ with enemy soldiers ‘without any consideration of nationality, race and family honour’. Prohibitions and threats of punishment showed hardly any effect, however. On the ‘home fronts’ the circumstances of prisoners connected in a general sense with the social situation found in the warring states.

The responsible government authorities noted with alarm, as did the relevant economic circles, that the enemy under their power were ready to join in the workers’ struggle of the home population. That was also the case in varying degrees with Russia and the Danube Monarchy. In the Austro-Hungarian army administration, for instance, more and reports were filed of ‘passive resistance’ and strikes, in which Russian prisoners of war also took part.

The relations between the civilian population and the ‘foreign soldiers’ are highlighted by means of a spontaneous demonstration in Vienna, for instance. In May 1917 passers-by had seen a group of Russian prisoners of war there, who were moving with difficulty, eventually ‘breaking ranks’ and asking for bread ‘with raised hands’. The accompanying guard attempted to re-establish ‘order’ using force. At which point women and children poured on to the street, screaming: ‘Shame on you! Stop making war, when there’s nothing left to eat, that’s how it will be for our poor devils in captivity’.

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Gefangenschaft, Revolution, Heimkehr. Die Bedeutung der Kriegsgefangenenproblematik für die Geschichte des Kommunismus in Mittel- und Osteuropa 1917–1920, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2003

Moritz, Verena/Leidinger, Hannes: Zwischen Nutzen und Bedrohung. Die russischen Kriegsgefangenen in Österreich (1914–1921), Bonn 2005

-

Chapters

- Numbers and Dimensions

- Captivity

- The situation of prisoners of war in Austria-Hungary

- Humanitarian catastrophes in captivity

- Aid for prisoners for war

- National propaganda and prisoners of war

- The relationship between prisoners of war and the civilian population

- The Meaning of Prisoners’ Labour

- Witnesses and actors in the revolution

- ‘Transport Home from Captivity’

- Difficult Homecoming