The situation of prisoners of war in Austria-Hungary

As early as late summer 1914, surprise was registered concerning the rapid rise in the numbers of prisoners of war in the 10th Department of the Austro-Hungarian War Ministry, which dealt with matters relating to soldiers captured in combat. After all, there were around 200,000 enemy soldiers in the hands of the Danube Monarchy, confronting the military authorities with new challenges.

In Austria-Hungary, around 50 large prisoner of war camps were built in the course of the war as well as officer stations for captured officers, internment and work camps. However, the Austro-Hungarian military authorities underestimated the sanitary, hygiene-related requirements for the large camps. The typhus epidemic that raged through various Austro-Hungarian camps in the winter of 1914/15 (e.g. in the Mauthausen camp or at Marchtrenk in Upper Austria) illustrated the failings in dramatic fashion. In Mauthausen several thousand captive Serb soldiers died in the early months of the war.

The constructional measures adopted as a result were able to solve the hygienic problems to a large extent and stem the health risks in the prison camps, yet from 1915 prisoners of war saw themselves confronted by a new, heterogeneous dimension in their experience as captives: mostly teams who were interned were commandeered to labour in the surrounding land or around bases and at the front. The camps lost in significance. Moreover, this deployment of labour gave rise to the broad area of abuse and treatment that violated international law. In many cases the fate of prisoners of war evaded the control of central authorities. Above all those forces working as the so-called “army in battle” were utterly at the mercy of those in command at the local level.

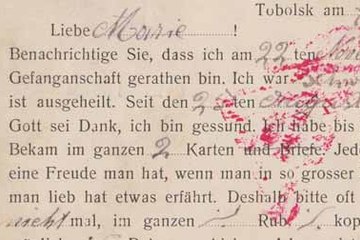

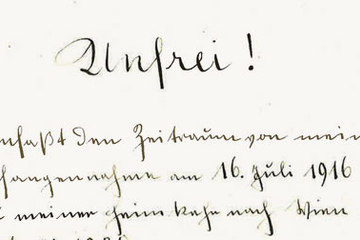

The situation of prisoners in Austria-Hungary can be seen not least of all in the context of the shortfall in supplies increasingly the case from 1916 onwards. Thousands of prisoners died of disease, exhaustion and malnourishment. Many prisoners complained in their letters to loved ones in their homeland about the wretched situation in Austro-Hungarian captivity. There are no reliable figures for mortality rates among prisoners in Austro-Hungary.

The International Red Cross, national Red Cross societies, the Vatican, the YMCA or neutral states in their function as protective powers all attempted to improve the lot of prisoners of war in the various states by means of humanitarian relief operations from 1915 onwards. However, the success of this involvement through the prisoners of war policy of Austria-Hungary as guided by the so-called ‘reciprocity principle’ lagged behind expectations. Those responsible in the Danube Monarchy were at pains to present the soldiers in Austro-Hungarian captivity in the most favourable light possible, although internally one was perfectly well informed about the many inadequacies of the prisoners’ situation. When in 1918 an Austro-Hungarian officer inspected prisoners who were deployed as labour in Vienna, he was of the opinion that on account of their weakened physical condition one was dealing with nothing less than ‘death candidates’.

Many officers appealed to the reputation of the Monarchy whenever they revealed the defects in the treatment and provision of prisoners. At the same time, however, the dismal supply situation seemed to render any discernible improvements in the prisoners’ situation virtually impossible, especially in the last two years of the war.

A significantly better lot than that of the ordinary soldiers who had been taken prisoner was granted to captured officers, who were to be treated in accordance with the provisions of the Hague Convention of 1907 and who were allowed to be drawn upon for labour only in a very restricted capacity. For strategic reasons they were quartered in so-called ‘stations’ for officers. The winding-up of these facilities and the relocation of the officers to separate areas of the POW camp from summer 1915 changed nothing in their privileged status. So in general a distinction must be made between two separate worlds of experience of captivity in the First World War – between that of the officers, and their men.

While the attempt was made after the war, mainly by former Austro-Hungarian officers, to present captivity in Austria-Hungary as practically paradisiacal, a closer examination of the situation of captive soldiers in the Habsburg Monarchy does not permit a characterisation of this kind.

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Gefangenschaft, Revolution, Heimkehr. Die Bedeutung der Kriegsgefangenenproblematik für die Geschichte des Kommunismus in Mittel- und Osteuropa 1917–1920, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2003

Moritz, Verena/Leidinger, Hannes: Zwischen Nutzen und Bedrohung. Die russischen Kriegsgefangenen in Österreich (1914–1921), Bonn 2005

Oltmer, Jochen (Hrsg.): Kriegsgefangene im Europa des Ersten Weltkriegs, Paderborn/München/Wien 2006

-

Chapters

- Numbers and Dimensions

- Captivity

- The situation of prisoners of war in Austria-Hungary

- Humanitarian catastrophes in captivity

- Aid for prisoners for war

- National propaganda and prisoners of war

- The relationship between prisoners of war and the civilian population

- The Meaning of Prisoners’ Labour

- Witnesses and actors in the revolution

- ‘Transport Home from Captivity’

- Difficult Homecoming