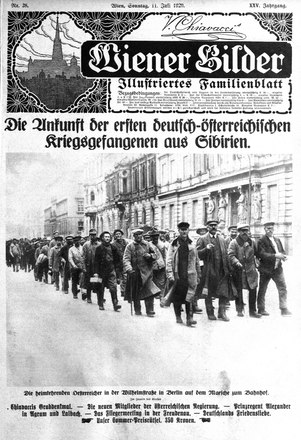

‘Transport Home from Captivity’

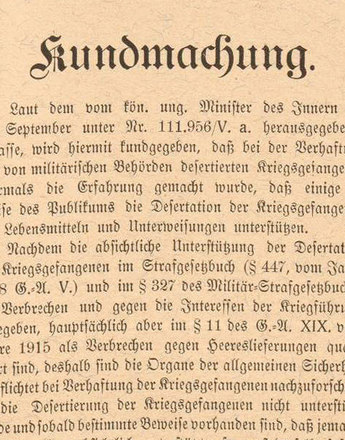

The return home of hundreds of thousands of prisoners of war took place towards and after the end of the First World War under circumstances of revolution. Regular evacuation methods were hard to carry out in the wake of the upheavals in Central and Eastern Europe. To this was then added the mistrust felt towards the prisoners by those back home. Defensive measures were taken, which likewise set up conflict.

Although – as part of the peace agreement reached with the Bolsheviks in Brest-Litovsk (on March 3, 1918) – the Central Powers sought to release as few Russian prisoners as possible yet get back all the more of their own soldiers, the latter were not especially welcome, neither in Germany nor in Austria-Hungary. The imperial-royal War Ministry together with the army chief command thus set up camps to monitor and discipline the nigh-on 700,000 men who reached their own army front lines, often by back routes and more rarely by regular transport. The reception, anything but warm, the general war-weariness as well as the social and economic crisis, and less the Soviet ‘revolutionary ideas’, accounted for several mutinies among the former prisoners of war.

Meanwhile anti-Bolshevist ‘white’ governments and the great powers allied with them considered the half million soldiers of the Central Powers as still their prisoners, especially as they did not recognise the rulings of the Brest Treaty. A declaration to this effect of October 23, 1918 originated from the ‘All-Russian Government in Omsk’. A few days later, on November 3, some 300,000 soldiers of the Habsburg army were taken prisoner by the Italian armed forces, after communication problems as a result of the ceasefire negotiations.

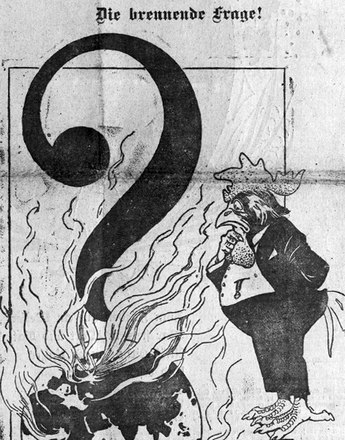

While in the coming months many Entente soldiers, who had found themselves held captive by the collapsing Habsburg and Hohenzollern empires, were repatriated or set off home on their own, it took longer for the losers of the First World War. After corresponding agreements with the western powers, it was finally Russia that proved the greatest problem.

Other complicating factors that hindered repatriation actions were the unrest in the Danube area, the establishment of short-term council-based republics in Bavaria and Hungary as well as the conflicts between the successor states of the Danube Monarchy. In many places, too, the flow back home of Bolshevist-influenced men from the former territory of the Russian Empire was awaited with scepticism.

The definitive solution to the repatriation problem could be achieved with help of the Red Cross and the League of Nations, as well as with international cooperation. Ultimately of particular significance also were the concessions made by the Soviet Union, which had conquered its opponents in most regions of the former Romanov Empire, and had reached bilateral agreements with various European states, including the Republic of Austria, at the beginning of the 1920s.

It was under these conditions that initially 100,000 ‘new Austrians’, i.e. citizens of the young First Republic, returned home from Italy, mainly. Between January 1920 and March 1922 nearly 120,000 former Austro-Hungarian soldiers then came back from Soviet territory, of which 25,000 were ‘new Austrians’. On the part of the government in Vienna, the return of prisoners of war was thus considered finished. From 1922/23 onwards, responsibility for repatriation of late returning men lay with the Ministry of the Interior, and subsequently the Federal Chancellery.

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Die Repatriierung der k. u. k. Kriegsgefangenen 1918 bis 1922, in: Politicum, 28. Jg., Nov. 2007, 102: 1918 – Der Beginn der Republik, 53-56.

-

Chapters

- Numbers and Dimensions

- Captivity

- The situation of prisoners of war in Austria-Hungary

- Humanitarian catastrophes in captivity

- Aid for prisoners for war

- National propaganda and prisoners of war

- The relationship between prisoners of war and the civilian population

- The Meaning of Prisoners’ Labour

- Witnesses and actors in the revolution

- ‘Transport Home from Captivity’

- Difficult Homecoming