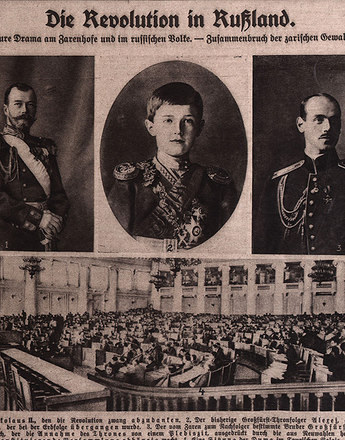

Witnesses and actors in the revolution

The end of the Tsarist domination and the ‘October Revolution’ was linked in the minds of prisoners of war in Russia above all with the hope of a speedy return home. Those soldiers who had themselves experienced close-up the emergence of Soviet power and thus a realignment in world history were less than receptive to Bolshevik ideology.

The Bolsheviks’ peace slogans impressed many German and Austro-Hungarian soldiers who were living on territory of the former Tsarist Empire. Yet relatively few prisoners of war had actively taken part in Lenin’s seizure of power in October and November of 1917.

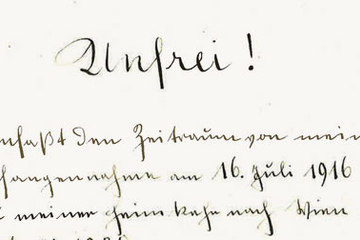

The policy towards prisoners adopted by the Soviet government proved to be devious at its core. While it declared ‘foreign working persons’ to be free on the one hand, it made the benefits of new provisions valid only for those who sympathised with the new regime, on the other. A policy that targeted officers above all dragged the class war into the camp and into the work places of the former foes.

Overall the ‘foreigners’ were ultimately seen rather as a de-stabilising factor in Lenin’s territory. With the breaking-up of the old Tsarist army, many Russian home-comers saw the prisoners as rivals for jobs. Moreover, the Bolsheviks, who now soon called themselves Communists, distanced themselves from their own proclamations of freedom. Accordingly, the Communist Party, which quickly turned the young Soviet republic into a one-party dictatorship, attempted to stop the ‘uncontrolled moving around’ of prisoners of war.

The Bolsheviks did not obstruct their repatriation in any major way, however. Yet efforts were still made to indoctrinate their worldview so as to turn the returning soldiers into carriers of a ‘bacillus of Bolshevism’, as Lenin described it. The majority of former prisoners showed themselves to be unimpressed by it, however: they did not carry out the expected putsch in their countries of origin, modelled on the Russian Revolution.

In the end, evacuation measures even worked out badly against the Bolsheviks. Permanent tensions between the Soviet organs and the departing Czechoslovakian legionaries turned into an open conflict. The ‘Czech Uprising’ favoured anti-communist forces in Russia and had a considerable influence on the anti-Soviet intervention of foreign powers.

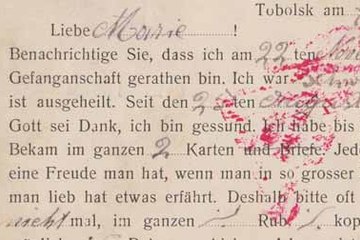

Hundreds of thousands of prisoners of war could no longer be transported home due to these events. They remained unwanted in Siberia mainly, where – like in other regions of the former Tsarist Empire – bloody fighting broke out between supporters and opponents of Lenin. Many German and Austro-Hungarian soldiers became witness in this way to the armed conflicts and catastrophic economic crisis on the territory of the former Romanov Empire.

And so many Central Power soldiers experienced the revolution as a period of terror. That a minority of them – estimated at some ten thousand – signed on with the Red Army, at that time being built up, was probably often to do with the food provided by the military. Only a small number of convinced Communist Party officials from the ranks of the prisoners of war were committed unconditionally to the Bolsheviks. They joined the Soviet security organs and the foreign groups in the Russian Communist Party, constituted the founding personnel of the Third International, and set up left-wing, radical, communist and pro-Soviet organisations in their home countries.

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Gefangenschaft, Revolution, Heimkehr. Die Bedeutung der Kriegsgefangenenproblematik für die Geschichte des Kommunismus in Mittel- und Osteuropa 1917–1920, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2003

Mohr, Joan McGiure: The Czech and Slovak Legion in Siberia, 1917–1922, Jefferson et al. 2012

-

Chapters

- Numbers and Dimensions

- Captivity

- The situation of prisoners of war in Austria-Hungary

- Humanitarian catastrophes in captivity

- Aid for prisoners for war

- National propaganda and prisoners of war

- The relationship between prisoners of war and the civilian population

- The Meaning of Prisoners’ Labour

- Witnesses and actors in the revolution

- ‘Transport Home from Captivity’

- Difficult Homecoming