On the Eastern Front, significantly more soldiers fell into enemy hands than on other battlefields. What were the key reasons for that? Were, for example, the soldiers of the Habsburg army ‘demoralised’ earlier by the events of the war than others? Or was it even a lack of loyalty towards the Danube Monarchy that caused them to switch sides?

Up to 1914, to be overwhelmed by the enemy was considered inglorious in martial thinking, above all when those concerned handed over their weapons without being injured. Back home they could expect investigation proceedings as well as not infrequently the contempt of their fellow countrymen, who accused prisoners of cowardice or even high treason.

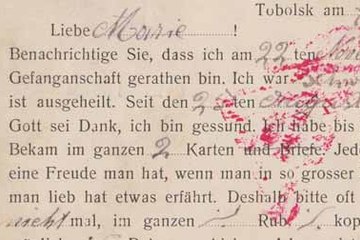

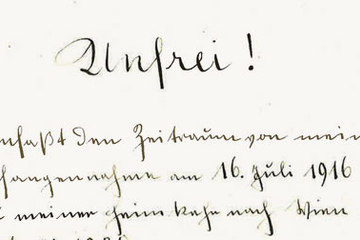

Accordingly, those participants in the war who found themselves in the hands of the enemy for some time were at pains to rebut such allegations. Certainly telling events as they happened, it was precisely officers who described in their memoirs that they had at times made several attempts at escape so as to reach their homeland.

Apart from this, it was emphasised that the suspension of hostilities in hectic fighting was a threat to life, and that soldiers were killed after being captured. Cruel scenes occurred mainly due to widespread stories of enemies who only pretended to surrender, and then grabbed their guns after their supposed capitulation. In contrast to officers who as a rule were allowed to expect correct treatment, the common soldiers had to reckon with acts of violence after their capture too and after initial interrogation on the part of enemy troops.

Given this, it should come as no surprise that a capitulation was out of the question for many soldiers at the front, and that, for example, the British armed forces up to the end of 1916 took few soldiers of the Hohenzollern army prisoner. The number of prisoners of war probably rose in the West with the battles of attrition, too, while in the East the losses due to prisoners taken were significantly higher. The percentages of POWs among the French amounted to 12%, among the Germans 9% and among the British 7%; the comparable number among soldiers of the Tsarist and Habsburg armies was in excess of 30%.

In view of such numbers, a weaker will to fight could be identified especially in the multi-ethnic army of the Danube Monarchy, and a greater tendency to desert to the other side. Statistics, however, cannot confirm such assumptions. The percentage of individual nationalities in the Austro-Hungarian soldiers to be found in Russia corresponds – with slight variations – to the percentage of the individual ‘peoples’ in Austria-Hungary and in particular in the Habsburg military forces. The Czechs, often described as unreliable, were even under-represented among prisoners of war in the Russian Empire.

The fact that the high number of Magyars in captivity there lay somewhat above their overall share of the imperial-royal army could be attributed above all to the make-up of the Habsburg troops on the ‘Russian front’. Here encircled and beaten fighting formations repeatedly fell into enemy hands as one, and thus correspondingly more Hungarian soldiers were taken prisoner.

Ferguson, Niall: Der falsche Krieg. Der Erste Weltkrieg und das 20. Jahrhundert, Stuttgart 1999

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Gefangenschaft, Revolution, Heimkehr. Die Bedeutung der Kriegsgefangenenproblematik für die Geschichte des Kommunismus in Mittel- und Osteuropa 1917–1920, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2003

-

Chapters

- Numbers and Dimensions

- Captivity

- The situation of prisoners of war in Austria-Hungary

- Humanitarian catastrophes in captivity

- Aid for prisoners for war

- National propaganda and prisoners of war

- The relationship between prisoners of war and the civilian population

- The Meaning of Prisoners’ Labour

- Witnesses and actors in the revolution

- ‘Transport Home from Captivity’

- Difficult Homecoming