National propaganda and prisoners of war

To weaken empires with many peoples in it by supporting national opposition movements was a strategy pursued by many warring powers. That the multi-ethnic monarchies of the Romanovs and the Habsburgs should use such methods themselves proved to be a dangerous game, however.

Germany tried to destabilise Russia on several levels. Berlin wanted to bring conquered territories in part under permanent, direct control. Moreover, one occasionally took advantage of the minorities in the border regions. Furthermore, the goal was pursued of building buffer states against a reduced Romanov Empire. Local opponents of the regime as well as social-revolutionary forces were also deployed in order to create unrest in the centres of the Tsarist Empire.

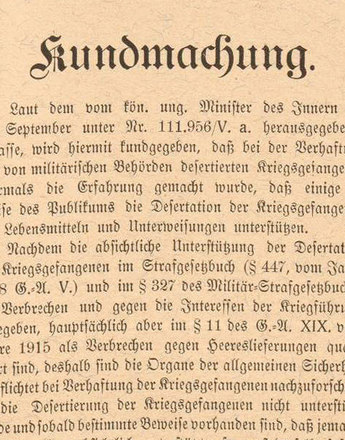

These measures also included national propaganda spread among prisoners of war. Apart from the bringing together of Islamic soldiers of the Russian army, who were to be released from captivity and put at the disposal of the allied Ottoman Empire as reinforcements, the Hohenzollern and Danube Monarchy concentrated in particular on ‘separatist propaganda’ among the captured Georgians, White Russians, Ukrainians and Poles. They were to be accommodated in separate camps, to rise up against St. Petersburg, to prepare revolutionary acts, or at least to form their own national troops as part of the German and Austro-Hungarian army.

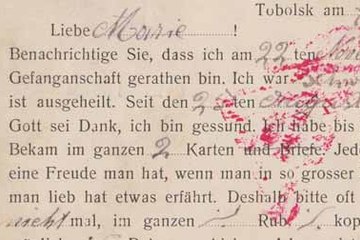

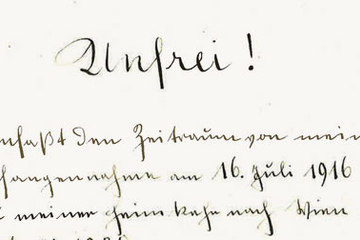

But such endeavours proved problematic. A Kingdom of Poland as proclaimed by the Central Powers at the end of 1916 did not yet have clearly defined powers and firmly delineated territories. The locals remained distanced; the legions set up by them did not want to be turned into auxiliary troops of the Germans and Austrians in the long term. Moreover, those concerned had been staying several months in the internment locations without finding out what was to happen to them. A Polish prisoner from the Tsarist army wrote to his family in this regard: ‘They let no one go home and no one knows how this will end, except that we are dying of hunger ...’ In March 1917 this propaganda activity among the Polish prisoners of war was suspended ‘on orders right at the top’ from Emperor Karl, after shortages in supplies and numerous escape attempts had occurred at the places of accommodation.

One had to factor in several imponderables when it came to influencing the Ukrainian soldiers in the Tsarist army, too. Exile organisations, assigned with the ‘enlightenment’ of the men, revealed themselves in many cases to be strongly socialist-minded bodies. Their ideas hardly fitted therefore with the constitutional, monarchical principles of the decision-makers in Berlin and Vienna. Moreover, an independent Ukraine had to have repercussions for the rival ethnicities of Galicia, as had the creation of a Polish state, and had to cast doubt upon the previous borders of the Danube Monarchy.

Meanwhile, the military within the Romanov Empire had likewise foreseen ‘national separation’. In special camps the Slavic ‘subjects’ of the Habsburg Empire, who as Austro-Hungarian soldiers had landed in Russian captivity, were offered certain advantages and perks. In general, efforts were made in St. Petersburg to send Hungarians, Germans from Austria and Germany itself to far-off regions of Siberia and Turkestan, while Czechs, Slovaks, Slovenians, Serbs and Croats were meant to remain rather within the European part of Russia.

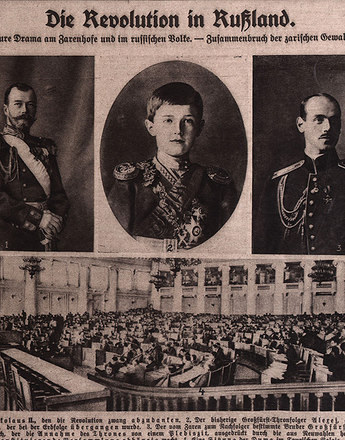

Such measures were certainly not rigorously applied, however. With just as little energy was propaganda undertaken for national combat units. An increased level of campaigning only set in when the Tsar had been deposed. Now the Czechoslovakian Legion in particular developed into a significant fighting force. Following the ‘October Revolution’ it then played an unexpected role, however – as the spearhead of the allied interventionist troops and the counter-revolution within Russia – in the struggle between opponents and advocates of the new Soviet regime.

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Gefangenschaft, Revolution, Heimkehr. Die Bedeutung der Kriegsgefangenenproblematik für die Geschichte des Kommunismus in Mittel- und Osteuropa 1917–1920, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2003

-

Chapters

- Numbers and Dimensions

- Captivity

- The situation of prisoners of war in Austria-Hungary

- Humanitarian catastrophes in captivity

- Aid for prisoners for war

- National propaganda and prisoners of war

- The relationship between prisoners of war and the civilian population

- The Meaning of Prisoners’ Labour

- Witnesses and actors in the revolution

- ‘Transport Home from Captivity’

- Difficult Homecoming