More than a dozen different languages were spoken within the borders of the multi-ethnic Habsburg Monarchy. Some, however, enjoyed higher prestige than others. The course of history had seen constant change in the relative values of the various tongues.

In pre-modern times different languages had different functions, each one being used in a precisely defined context or in certain situations. This is obviously true of Latin, which was the language of the Roman Catholic Church. The high esteem it enjoyed as the language of the liturgy resulted in it becoming the language of scholarship. Raised on high above the level of everyday idioms, Latin was an elevated language with an aura all of its own.

A similar situation obtained in the Slavic Orthodox countries, where Old Church Slavonic was used by the Orthodox for their liturgy and religious literature. For the same reasons, ancient and patristic Greek enjoyed the same high regard in the Byzantine world.

For the Jews, Hebrew was the ‘sacred language’ reserved for the religious field and for special areas such as scholarship and law, while their everyday language was either Yiddish or whatever language was spoken by the majority of the local population.

Amongst the Bosniaks, who were Moslems and had long been under Ottoman rule, it was Arabic, as the language of the Koran, that possessed a special position, with other oriental languages such as Persian and Turkish being the languages of literature and administration. However, the everyday tongue spoken by the Bosniaks was a Slavonic language.

The higher-ranking languages nevertheless also exerted a certain influence on the everyday idiom. When the various vernacular languages were first written down, it was generally the script of the ‘high’ language that was adopted. As a result, although the Bosniaks were Slavs, they wrote their language with Arabic letters; similarly, Romanian was written in the Cyrillic script until well into the nineteenth century, in spite of it not belonging a Slavonic language. Yiddish, on the other hand, is still written with the Hebrew alphabet today, even though it had developed out of Middle High German, as the commercial language of the eastern European Ashkenazi Jews.

In the Enlightenment at the latest there was a change in the hierarchy of the languages. In Central Europe German took over the role of Latin in many areas of life, notably government and scholarship. In addition, however, a mastery of certain other languages was obligatory amongst the educated classes, French as the language of conversation of the elites all over Europe, for example, or Italian as the language of art and music.

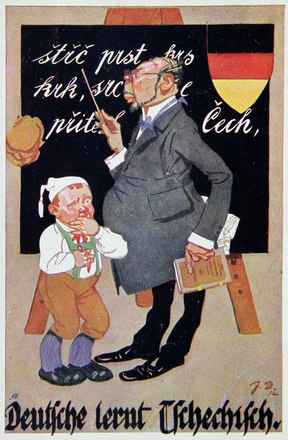

All over the Habsburg lands German developed into the supraregional language of commerce and administration of the social and economic elites. This development started during Maria Theresa and Joseph II’s programmes of centralization and reform, when one single language was required for the central bureaucracy and as a language of command in the army – and as German was a kind of ‘lowest common factor’, it was the obvious choice.

However, these endeavours at unification met with a certain resistance. The local nobilities, who represented the respective lands and feared for their monopoly over local adminstration and judicature, reacted by emphasizing the special characteristics that made their region different from others. This went hand in hand with the ‘rediscovery’ of linguistic traditions that had mostly fallen into disuse in the course of history: the Bohemian nobility, for example – regardless of their ethnic origins – took to championing the Czech language, which had been the most important language of administration in the Bohemian lands in the late medieval and early modern period, as an expression of their opposition to the unification programmes being imposed by the Habsburg central administration. The situation was similar with the Hungarian language, the use of which was regarded as an expression of loyalty to the Hungarian crown. In Galicia Polish and in Croatia Croatian also acquired a new significance as the languages of feudal rule by the local estates.

Translation: Peter John Nicholson

Kann, Robert A.: Zur Problematik der Nationalitätenfrage in der Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, in: Wandruszka, Adam/Urbanitsch, Peter (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, Band III: Die Völker des Reiches, Wien 1980, Teilband 2, 1304–1338

Křen, Jan: Dvě století střední Evropy [Zwei Jahrhunderte Mitteleuropas], Praha 2005

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

-

Chapters

- The birth of nations

- The hierarchy of languages

- ‘Tell me what language you speak and I will tell you who you are.’

- Unity in diversity? The failure of the idea of a ‘greater Austrian’ nation

- The role of history: Concerning ‘historic’ and ‘history-less’ peoples

- The drive for unification

- The role of schools in the growth of national identity