‘Tell me what language you speak and I will tell you who you are.’

In the Habsburg Monarchy it was common for the nobility and bourgeoisie to use a different language that set them apart from the peasants and urban lower classes who formed the majority of the population.

Another typical feature of Central Europe was that language borders were not determined so much by geography as by social factors. Membership of a certain social group was not only determined by lifestyle but also by the use of certain languages. In many areas the majority of the population spoke a different language from the elites. Language also marked the difference between town and country, because towns were often German-speaking islands within areas largely inhabited by non-German-speakers. The famous saying ‘Town air makes you free’ could justifiably be adapted to make this point: ‘Town air makes you German’.

The ‘Volk’, on the other hand, communicated in a regional dialect or even in a vernacular language that was usually not written down. Sometimes, as for example in the case of Slovak and Slovene, there was hardly any literature at all, and if there was, then usually in archaic forms deriving from translations of the Bible or religious writings from the time of the Reformation. The churches played a particularly important role in the preservation and cultivation of Central European languages, particularly of the less widespread ones. As it was critically important for pastoral purposes that ministers of the Church should understand the local language, the only existing printed texts in the language were usually religious in character: collections of sermons, hymns, devotional literature and the like.

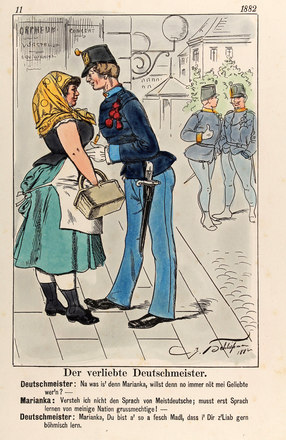

Another phenomenon was the ‘functional multilingualism’ – meaning the the practice of choosing one’s language in accordance with the respective context or occasion. This switching between languages could depend on the social context or the social status of the person being addressed, but also on the content or level of the conversation being held or letter being written. One result of this was dialects being subject to mixed influences, which generated hybrid forms of sociolect such as the ‘water Polish’ (‘Wasserpolakisch’) spoken in Silesia, which had a mixed population of Germans and Poles, or the ‘kitchen Bohemian’ that was a mixture of Czech and German elements.

Cross-border communication also often took place in a language different from the local tongue. This also had an influence on the way the area in question was perceived, with Bohemia and Carniola, for example, being regarded as German-speaking areas because German was the language of administration and commerce even in areas where the majority were not German-speakers.

The fact that the various languages enjoyed different levels of prestige led to the phenomenon of linguistic acculturation. For many members of smaller language groups, acquiring education and rising in society meant having to adapt to fit into a milieu with a different lingua franca. Most of those who bettered themselves economically and rose in society had to change language, and then later also their national identity, which led to a massive ‘brain-drain’ to the advantage of the dominant language group. The cultural elites of the Habsburg Monarchy often adopted German manners and cultural practices, even when they were themselves not of Germanic origin.

The leaders of the national rebirths of the smaller peoples promoted consciousness of the respective languages and thus exerted a dampening effect on the primacy of the German language. A veritably missionary zeal was brought to encouraging fellow nationals to make an open display of their loyalty to their respective language. Writings published to defend this or that language made a point of emphasizing its time-hallowed and venerable character. There was a deluge of geographical, ethnographic and linguistic publications seeking to reconstruct the (usually highly obscure) historical traditions of the various nationalities. These developments were initially tolerated and even benevolently patronized by the German- or Hungarian-speaking elites, but only so long as they did not jeopardize the traditional hierarchy of languages. When, however, the consciousness of language promoted by the philological investigations led to mass enthusiasm and to demands being made that questioned that traditional hierarchy, the elites began to regard the endeavours as a threat to their hegemony.

Translation: Peter John Nicholson

Kann, Robert A.: Zur Problematik der Nationalitätenfrage in der Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, in: Wandruszka, Adam/Urbanitsch, Peter (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, Band III: Die Völker des Reiches, Wien 1980, Teilband 2, 1304–1338

Křen, Jan: Dvě století střední Evropy [Zwei Jahrhunderte Mitteleuropas], Praha 2005

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

-

Chapters

- The birth of nations

- The hierarchy of languages

- ‘Tell me what language you speak and I will tell you who you are.’

- Unity in diversity? The failure of the idea of a ‘greater Austrian’ nation

- The role of history: Concerning ‘historic’ and ‘history-less’ peoples

- The drive for unification

- The role of schools in the growth of national identity