Humanitarian catastrophes in captivity

The waiting at assembly areas and the transportation to the hinterland already entailed enormous exertion and suffering on the part of the many starving and often wounded prisoners. Once arrived at the destination in the hinterland, they then endured the lack of acceptable lodgings, especially to begin with. The camps in Central and Eastern Europe, in Siberia and Central Asia were locations of collective misery and mass death. Austria-Hungary was no exception in this regard.

While the English accommodated some 200,000 enemy soldiers basically in accordance with the regulations of international law, complaints mounted in France concerning the corresponding quarters for at least twice as many citizens of the Central Powers. The more soldiers were interned, the more difficult became their administration on the part of the military authorities. Near the front there was a lack of food supply and dwelling places; they were eventually transported away from the battlefield in cattle wagons without any appropriate protection against extreme winter conditions. The journey to the internment locations once again claimed more fatalities due to the inadequate measures, while the poor conditions were certainly not alleviated at the destination of their difficult journey.

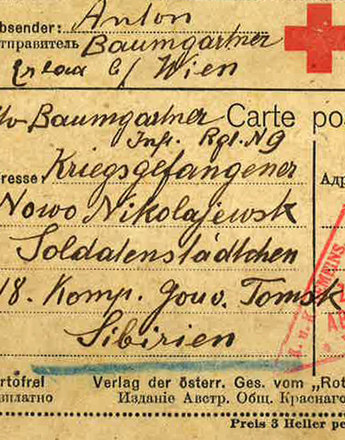

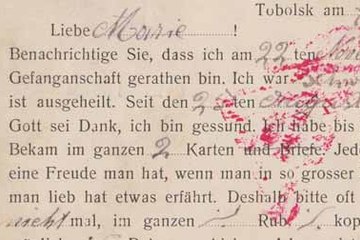

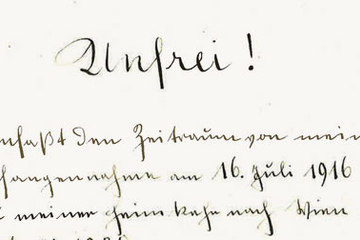

In the temporarily erected and overflowing quarters, infectious diseases spread. In Germany’s Brandenburg, for example, 7,100 of 9,700 prisoners fell sick with spotted fever around the turn of 1914/15. Dreadful mortality rates were recorded in the Romanov Empire meanwhile. In Novo Nikolaevsk, 80 percent of prisoners died in the winter of 1915; in Tockoe in the military zone of Kazan it was 60 percent up to March 1916. All in all several hundred thousand soldiers of the Central Powers are said to have died in the Russian Empire between 1914 and 1917.

In contrast, staff at the Austro-Hungarian army administration attempted long after World War One had ended to gloss over the situation in the Danube Monarchy. In reality, the propagated ‘better imprisonment’ in virtually ‘idyllic barrack villages’ was a distorted image. According to rough estimates, it appears that more than 100,000 of around a million Russians died in Austria-Hungary up to 1918, and around one third of all Serbs. Horrendous figures exist concerning the approximately 600,000 Italians interned by the Central Powers, too, of which more than one third were held captive in the Habsburg Empire. According to more recent investigations – which are, however, contended – around one sixth of them lost their lives from the poor living conditions. Prisoners of war therefore accounted for one quarter of all war-related deaths in the Apennine Kingdom.

The high fatality rate reflected primarily the organisational weakness and misjudgements on the part of the responsible authorities, yet also a difficult and steadily worsening supply situation in the countries prosecuting the war and especially in Central and Eastern Europe. Nonetheless, hostile images likewise contributed to the catastrophic conditions: West European prisoners were normally supported by their home countries. In contrast, Russia and particularly Italy mistrusted their ‘fellow countrymen in enemy hands’, who were sometimes branded defeatists. On the Austro-Hungarian side in turn, cultural arrogance towards the ‘Slavic East’ was as negatively perceptible as was the discernible hate towards the archenemies, ‘Italy’ and ‘Serbia’.

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Gefangenschaft, Revolution, Heimkehr. Die Bedeutung der Kriegsgefangenenproblematik für die Geschichte des Kommunismus in Mittel- und Osteuropa 1917–1920, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2003

Oltmer, Jochen (Hrsg.): Kriegsgefangene im Europa des Ersten Weltkriegs, Paderborn/München/Wien 2006

-

Chapters

- Numbers and Dimensions

- Captivity

- The situation of prisoners of war in Austria-Hungary

- Humanitarian catastrophes in captivity

- Aid for prisoners for war

- National propaganda and prisoners of war

- The relationship between prisoners of war and the civilian population

- The Meaning of Prisoners’ Labour

- Witnesses and actors in the revolution

- ‘Transport Home from Captivity’

- Difficult Homecoming