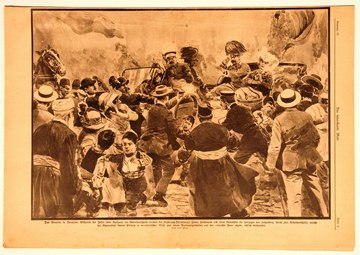

The assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne on 28 June 1914 is generally regarded as the cause of the First World War. However, the causal relationship between the two events is by no means as clear as it at first seems.

When the news reached Vienna, the reaction was one of shock but there were initially no feelings of desire for revenge. Archduke Franz Ferdinand was not particularly popular amongst the general public. There was thus no call for of an immediate retaliatory strike.

While the assassination was generally perceived by politicians in Vienna as a Serbian provocation, the war party saw it as completing the jigsaw of their line of argumentation – and proposed the use of military force to bring about a radical solution to the seething conflict. The shots fired at Sarajevo were thus not the culmination of some inexorable crisis imposed on Austria-Hungary through external circumstances but, rather, a welcome pretext in the eyes of the war-mongerers for the realization of long-held plans for a military escalation.

The ‘blame’ for the outbreak of war can clearly be put on the political decision-makers of the Habsburg Monarchy for their readiness to begin a war at all. Although the intention was to keep the conflict on a regional level, they were aware that in the worst case military intervention might ignite a conflagration that could spread all over Europe. Austria-Hungary thus consciously risked a world war, especially once it had gained assurance that it had German backing.

Decision-makers in army circles and in the diplomatic service had long since called for military action against Serbia. One of the most ardent advocates of a preventive war was the Chief of General Staff Conrad von Hötzendorf, who considered that the most favourable moments for a preventive strike had long since been missed. The generals considered that Austria-Hungary would have had a much better chance of success during the Bosnian annexation crisis in 1908/09 or in the Balkan wars of 1912/13 when Russia was weakened by internal unrest and the conflict with Japan. As Russia was now engaged in a massive phase of rearmament, to wait any longer would be to play into the hands of Austria’s enemies.

In addition, in an argument that seems to have convinced Franz Joseph, it was contended that Austria now had to defend its ‘wounded honour’ because nobody could be allowed to get away with shooting an heir to the Austrian throne – an example had to be set. It was hoped that solidarity would be shown by the European monarchs, in particular by the Tsar, who was known for his vigour in combating anarchistic tendencies in his own land. But this hope was misguided.

This was just one of many miscalculations: much against its better judgement, Vienna succumbed to illusions about its status as a great power. Hollow power-posturing, loud threats and bold gestures were used to conceal the fact that Austria-Hungary was not politically, economically, or militarily prepared for a long-drawn-out conflict, and certainly not for a war on several fronts. The politicians ignored all warnings and proceeded on the false assumption that hostilities would last only a matter of months. They were convinced that with the backing of Germany they would soon be able to create concrete preconditions for a new ordering of the Balkans in accordance with Austrian interests.

Translation: Peter John Nicholson

Bihl, Wolfdieter: Der Erste Weltkrieg 1914–1918. Chronik – Daten – Fakten, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2010

Hanisch, Ernst: Der lange Schatten des Staates. Österreichische Gesellschaftsgeschichte im 20. Jahrhundert [Österreichische Geschichte 1890–1990, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Leidinger Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Der Erste Weltkrieg, Wien [u.a.] 2011

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien u. a. 2013