-

"Love me and the world is mine!", Germany's grab for world dominance, British propaganda postcard, published by W.R.W & Co, Glasgow, 1914/15

Copyright: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H. / Objekt aus der Sammlung Dr. Lukan

-

“The Entente of cripples”, propaganda postcard

Copyright: Wien Museum

-

“La brutta Triplice”, Italian propaganda postcard, around 1915

Copyright: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur-und Betriebsges.m.b.H./Fotograf: Alexander E. Koller / Objekt aus Privatbesitz

-

Political overview map of Europe around 1914

Copyright: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur-und Betriebsges.m.b.H./Fotograf: Alexander E. Koller

At the end of the nineteenth century distinct fault-lines began to appear in the traditional system of great powers that had been established at the Congress of Vienna (1814/15) to promote the balance of power. Significant shifts were taking place in the European power structure.

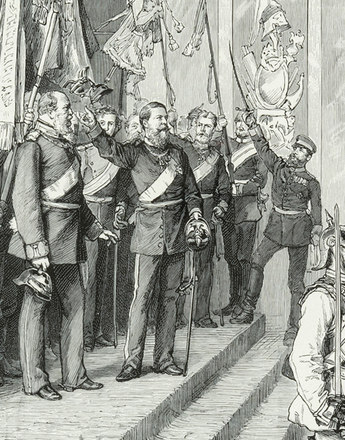

Two new great powers had arisen in the form of Germany and Italy, both of which had emerged as solid nation-states after long processes of unification. As a result certain of the ‘classic’ great powers became less important: more specifically, not only was the Ottoman Empire rapidly disintegrating and thus throwing European politics seriously out of kilter, but a Habsburg Monarchy shaken to its foundations by internal crises was becoming more and more of a giant with feet of clay.

Germany now became the power with the say in Central Europe. Once Bismarck’s consistent pursuit of great power status had led to the unification of 1871, the German Empire laid claim to a role in global politics commensurate with its newly won importance. Its aggressive behaviour led to a deepening of its enmity with France and Russia. In addition, its massive colonialist activities brought it into competition with its traditional ally Great Britain. Germany was now increasingly isolated in Europe, largely as a result of its own insensitive diplomacy. In 1904 France and Great Britain concluded the defensive alliance known as the Entente cordiale, which in 1907 became the Triple Entente when Russian joined. Surrounded by enemy powers, Germany felt seriously threatened, even fearing for its very existence.

Great Britain, whose principal goal was the expansion and consolidation of its worldwide colonial empire, was interested in preserving the European status quo and maintaining the traditional balance of power in Europe, which would be seriously upset if Germany were to become the strongest power on the continent.

As for France, it had been looking for an opportunity to take revenge on Germany ever since the Franco-Prussian war of 1870/71: Wilhelm I’s proclamation as Emperor of the German Reich in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles was still perceived as a national humiliation. Paris had increasingly hostile relations with Berlin, as was reflected in efforts by France to win back Alsace-Lorraine, which it had had to cede to Germany in 1871.

Tsarist Russia, for its part, was striving to overcome its own internal crisis and consolidate its status as a great power. On the European front it had once again become active against the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans and around the Black Sea, asserting its role as the protector of the Slavs of the Orthodox faith. In its involvement in south-eastern Europe Russia clashed with the interests of Austria-Hungary, which was likewise seeking to expand in the Balkans. In the overall scheme of things the Western Powers saw Russia as an important partner with the role of checking Germany’s drive for hegemony in the east.

Translation: Peter John Nicholson

Bihl, Wolfdieter: Der Erste Weltkrieg 1914–1918. Chronik – Daten – Fakten, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2010

Bridge, Francis Roy: Österreich(-Ungarn) unter den Großmächten, in: Wandruszka, Adam/Urbanitsch, Peter (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, Band VI: Die Habsburgermonarchie im System der internationalen Beziehungen, Wien 1989, Teilband 1, 196–373

Leidinger Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Der Erste Weltkrieg, Wien [u.a.] 2011

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien u. a. 2013

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005