-

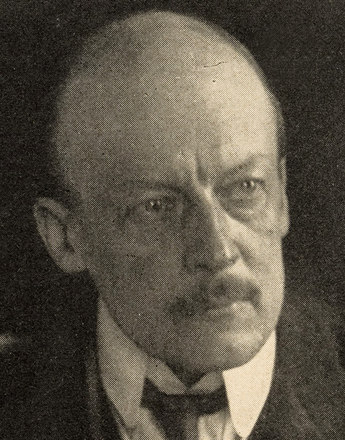

Adele Studio: Aloys Graf Lexa von Aehrenthal, portrait photo, 1907

Copyright: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur-und Betriebsges.m.b.H./Fotograf: Alexander E. Koller

-

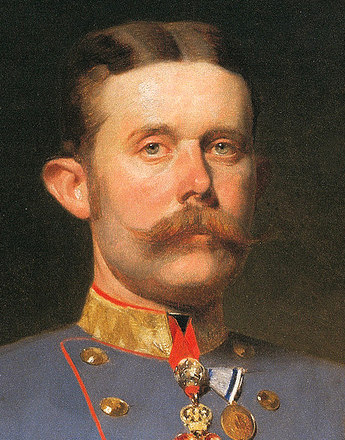

Leopold Graf Berchtold, Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister at the time of the outbreak of the war, illustration, 1917

Copyright: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur-und Betriebsges.m.b.H./Fotograf: Alexander E. Koller

Around 1900 there was a change of generation in the political leadership. Increasingly, the aged Emperor withdrew from day-to-day politics and became more of a symbolic figure.

Following the example of Franz Joseph, the traditional political elite also went into a state of resignation, unable to offer any solutions to the many problems they faced. One of the leading members of this often radically minded new generation was the heir to the throne Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Now in a more influential political position, Franz Ferdinand developed an independent line marked by a rejection of Dualism and a distinctly authoritarian vein of state centralism. Figures from the circle around the Archduke now took over key political positions and proposed assertive, power-oriented policies as the way out of the crisis.

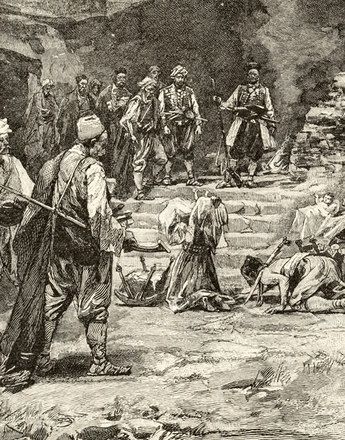

This also resulted in an important change in foreign policy, when in 1906 the long-standing foreign minister Count Gołuchowski was replaced by Aloys Lexa von Aehrenthal. Now, by contrast with earlier years when the priority in foreign policy had been to preserve the status quo, shows of strength were to be used as a catalyst for political developments at home. When Austria-Hungary decreed the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1908, however, it was playing with fire far too close to the Balkan tinderbox. This step, which was meant as a declaration of intent to fight Serbian expansionism, earned the Monarchy the bitter enmity of Serbia and of Serbia’s ally Russia.

In the army, too, a new generation also took over the reins of power, with Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf (1852–1925) becoming Chief of General Staff of the Austro-Hungarian army in 1906. This controversial figure was an adamant advocate of an aggressive policy oriented towards a preventive war against Serbia (and also possibly against Italy).

However, this undisguised policy of confrontation was rejected by the Emperor and also by such top-level politicians as the Hungarian Minister President Tisza and the Foreign Minister Aehrenthal, who succeeded in having Conrad von Hötzendorf removed from office in 1911.

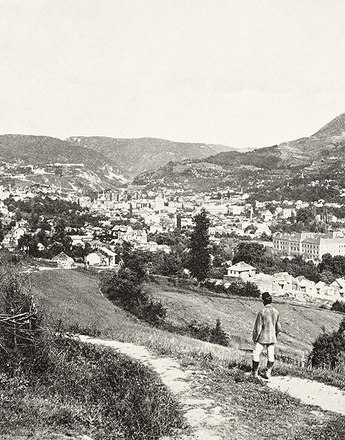

In 1912 Aehrenthal’s death led to another round of changes amongst the holders of high political office. The Foreign Ministry was taken over by Count Leopold Berchtold, whose Balkan policy was intended – even at the risk of a confrontation with Russia – to halt Serbia’s endeavours to become a great power. In spite of voices pleading for policies that would calm relations with Serbia, Conrad von Hötzendorf was reinstated as Chief of General Staff, with the result that war now became a realistic option. And when Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914, the war-mongerers saw it as an ideal opportunity for a ‘liberation strike’.

Translation: Peter John Nicholson

Beller, Steven: Franz Joseph. Eine Biographie, Wien 1997

Bihl, Wolfdieter: Der Erste Weltkrieg 1914–1918. Chronik – Daten – Fakten, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2010

Hanisch, Ernst: Der lange Schatten des Staates. Österreichische Gesellschaftsgeschichte im 20. Jahrhundert [Österreichische Geschichte 1890–1990, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien u. a. 2013

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005